A live online talk given in July 2020

Welcome everyone. Sarah Helm was a staff correspondent for The Sunday Times and a foreign correspondent for The Independent and she’s written two books, most recently, If This is a Woman about the Nazi concentration camp for women. And she has also written a play about the Iraq war and she’s currently working on a book about Gaza and before we started the broadcast, we were having a little chat about it and it sounds fascinating. So hopefully she’ll mention it and talk about it a little bit in her talk.

Sarah Helm:

Thank you so much Diana. Well, thank you everyone. And thank you very much to the Balfour Project for asking me along. The subject, Toppling Balfour, is dear to my heart for many reasons. I’ll mention two of them.

There’s a personal interest I have in Mr Balfour. I’m currently writing a book about Gaza very much from a historical perspective, looking at the villages from which the refugees who now live in Gaza, came from and trying to bring them back to life again and hearing the story through their voices. So this involves me going into houses a lot inside Gaza, and of course, as soon as I’ve stepped, in people look at me and they realise I’m English. And the next thing they say is ‘Balfour!’ Or else they say, ‘what have you got to say about Balfour?’

Or sometimes I get a whole tirade. And I feel like I’m taking all the flak personally for the Balfour Declaration. But mostly the people of Gaza are just very nice and gentle and they realise that I can’t really be blamed for everything that has happened as a result of the Balfour Declaration. So this talk is a chance for me to fire some flak back in his direction.

The second reason is more serious. As you know, we’re living in a time of toppling statues, particularly those connected with colonial crimes of the past – of slavery and exploitation of the “natives”, and other practises of the days of empire, when black lives didn’t seem to matter.

So the question is: should Balfour’s declaration, which granted a homeland for the Jews in Palestine in 1917, be examined in the same context? Did the Declaration and the way it was implemented suggest that for Balfour and leader of the British Mandate government – Palestinian lives didn’t matter

If so – given that there is no statue of him, should we bin his declaration?

Even if we agree the Balfour Declaration can be blamed for a lot of the conflict that has continued to this day, I have to just start by saying in his defence, it didn’t really begin with him – this colonial enterprise.

Europeans with colonial urgings were running around Palestine well before he got going. They were there in the mid-19th century. The Ottoman Sultan let this happen in many ways. He saw that his empire was crumbling and he needed Europeans as allies. So he allowed the Europeans to have special privileges. Consulates were opened, and they were given privileges called the capitulations, which meant they could operate outside of Ottoman law to some extent.

So with the consulates in place with these legal protections, it was felt that Palestine was safe for European visitors. And as a result, quite a lot of business opportunities opened up, trading with Europe began, steamers started arriving in Jaffa. And for example, we had a British consulate flag flying in Jaffa from quite an early time, as well – obviously – as in Jerusalem. The Vice-Consul was in Jaffa. At one point, his name was Chaim Amzalak, who got the job despite the fact that he didn’t even speak a word of English but he knew how the citrus trade worked and how to send off the best Jaffa oranges to England. A Jewish businessman from Morocco, Amzalak also was very much in favour of helping look for land for early Zionists, as were consuls of other European countries in Palestine at that time.

In addition to these businessmen, there were a lot of religious people heading out to the Holy Land, going to look for biblical relics and so on.

It was an age of Christian Zionism. We can think of people like George Elliot whose novel Daniel Deronda inspired many of these people. Mark Twain was another writer- traveller who visited, but people like Twain didn’t really notice the natives, or if they did, they didn’t think a lot of them. Mark Twain described the natives of Palestine as “immoral, ignorant, vain and bigoted”, and went back home, very disappointed.

Others, like the early British consul general, James Finn, were also dismissive of the natives but – despite themselves – seemed also to almost fall in love with the “fellahin” as the Palestinian peasant farmer was called. At least that’s my impression from his writings. Finn saw that the Fellahin were ignorant, as he put it. I mean, they were all illiterate, for sure, but he also noticed how incredibly skilful they were, for example, at playing their reed pipes, or planting a vine. He describes how the limbs of the arm were bent in such a way as to facilitate getting right down to the aquifer.

And the peasants were part of the land. This is the sense that one gets from these people who were studying the natives as specimens really. And they realised they’d become part of the land from having lived off the land there for hundreds and hundreds of years.

This throng of Christian Zionist visitors were dubbed a “quiet crusade”, but of course, the majority of these quiet crusaders didn’t stay. Some of them did, but most of them went back home again, once they’d studied their “specimens”.

Then there was also another group of European visitors, more serious in many ways: The Palestine Exploration Fund explorers. This was a group backed by the British government and funded by wealthy Brits. And amongst them were numerous rather extraordinary characters, including the young Horatio Kitchener, who arrived at the age of 26 and started triangulating Palestine – his task was to make maps.

In fact, the PEF explorers were mapping Palestine before a single Zionist colony had even been put there. So what they created, and Kitchener was part of this, was an extraordinary set of maps showing every single Palestinian village, every single Palestinian town, city, shrine, wadi, you name it, it was mapped – a snapshot of Palestine before Zionism even begun.

But of course this group didn’t really take a great deal of notice of the natives either. In fact,

Kitchener was also very rude about them. He describes how his men had stones thrown at them at one point and in response, he writes: ‘I had them publicly flogged,’ as if he already owned the place.

But later Kitchener also seems to have been somewhat seduced by the people of Palestine.

He discovered the Fellahin and the Bedouin were great company and – though illiterate –

were as he put it “intelligent fellows”, who he discovered he could “parley with”, and he’d be invited into a Sheikh’s tent for a long pipe and some dates, and they’d talk about falcons and camel riding and all sorts of adventurous things. And he got to like them a great deal, but also to respect them.

Kitchener remembers how after one such friendly encounter, he realised that the Palestinians were fellows who felt “an obligation to be true to people you have eaten with -and this obligation was sacred” I think he admired that sense of trust in the peasants, if we could put it like that.

And then of course, along came the earliest Zionists. These were different European visitors in many senses – not least because they weren’t visitors. They were going to stay. The early Zionists fled the appalling pogroms that were breaking out in Russia mostly at that time and were often living incredibly restricted lives in Russia’s Pale of settlement. Many of these early settlers were intellectuals, students, very religious Jews – all dreamers, all desperate to escape the hardships and the atrocities that they were experiencing.

And as they headed out to Palestine, many of them did not believe there were any Arabs there at all, which seems surprising, given reports coming out from other travellers, but nevertheless, it seems to be the case.

One such very early settler called Jacob Shertok went back to Russia very soon after he arrived, as he realised he couldn’t really make a go of it not only because he found Arabs already living here but because life was simply too hard.

Others like him, however, continued to come, especially when they managed to raise quite large sums of money, most notably from Edmond de Rothschild, which helped them survive in this very, very hostile environment. Hostile, that is, as far as working the land goes not as far as the local population goes, because in the early days there were so few Zionists that the Arabs had little chance to be hostile, and actually often tried to help them, until they felt threatened that is, which increasingly they did as their own lands were encroached on.

And so while the fellaheen -the peasants – continued to use their age-old ways of farming – planting vine saplings with bare arms – the new settlers were establishing colonial vineyards built with the latest state-of-the-art equipment brought in by ship, courtesy of Rothschild’s business partners in France.

As the colonies expanded it soon became impossible to pretend that this was an uninhabited land, not least because conflicts broke out between the new Jewish settlers and the Palestinian farmers nearby. Even so, the writings of these early Zionists rarely mention the Arabs they encounter in any meaningful way, just occasionally describing these primitive grotesque figures living around them –

rarely human, more often sub human.

I found a description by the Zionists who overtook the Palestinian village of Mullabes in 1878,where they went on to establish the very first Zionist colony called, Peta Tikvha. Visiting the village before buying the lands, they described creatures living in hovels who were: ‘blind and jaundiced, with puss pouring out of every eye.’

Before long those same creatures had been ejected, their “hovels” destroyed.

As we move on towards World War One, more and more of these small colonies beginning to take root in Palestine, as the Zionists are managing to buy more plots of land, usually by bypassing the Sultan’s laws, with the help of people like Chaim Amzalak, the British vice-consul in Jaffa. Amzalak and other European consuls, used the privileges granted to them under the “capitulations” to show the Zionists how to bypass the laws, and to advise on which corrupt Ottoman official they should bribe on the way.

Nevertheless, although the Zionists had a bridgehead in Palestine before World War One, the early settlers didn’t have anything like a majority – and it was a majority which they were determined to achieve, as their leaders declared right from the very start. In fact, by 1914 Jews were only about 2% of the population of Palestine.

So how on earth were they going to build on this small beginning? How could the Zionist overturn a majority of Arabs of 98%?

As World War One now breaks out you would imagine that this project is going to fall apart pretty soon. But no – quite the contrary, the British were going to help out, even while they were in the midst of fighting a global war.

It was now that the extraordinary determination of the Zionists began to emerge for all to see; the desire for a return to land, left 2000 years ago, was building into an apparently unstoppable force. And now they had their foothold, with a few small settlements, nobody among the Zionist leadership was going to let the chance of fulfilling the dream pass by, least of all those lobbying in London.

And there were very many powerful Zionists in London, even in the Cabinet and they had willing ears listening to them, particularly when they argued that support for Jews and Zionism could help Britain and its allies win the war. For example, we have Herbert Samuel who was in the cabinet and others in his ambit, including the persuasive Chaim Weizmann, all making this case that Jewish support for Britain around the world would be garnered if Britain said it would support a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and Jewish money would flow in to help pay for the war, they claimed.

Some other prominent Jewish figures, most notably, Edwin Montagu, another Cabinet member, opposed the Declaration outright saying it was “anti-Semitic”. Montague argued that if Palestine became the homeland for Jews “Jews will hereafter be treated as foreigners in every country but Palestine”.

But such arguments were dismissed and instead the claim that Jewish influence could help win the war, believed. I’ve actually seen extraordinary British intelligence documents, showing how seriously this was taken.

Actually, as it turned out, the claim was highly exaggerated – in fact largely false. But it was a theory that convinced Balfour and others that supporting the Zionist homeland would further British secure victory at a time when victory was very much in doubt.

But there are many other reasons why even before the war had ended the British supported the project. Balfour himself was something of a Christian Zionist, so he had sympathies with the biblical prophecies linked to the Jews return to Zion movement. But let’s not pretend that his declaration was formulated because he actually wanted to help Jews who were fleeing Russia. He didn’t. In fact, for several years Britain had been trying to reduce the numbers of Jewish refugees who were arriving in Britain as a result of persecution on the continent. America had all but stopped immigration after huge in-flows.

Some people even say that Balfour himself had anti-Semitic tendencies and may have hoped to divert Jewish immigration from Britain to Palestine I don’t know whether there’s any truth in that, but it’s been said.

The main motivation for the declaration was, however, to help protect British strategic post-war interests. Once the war was over and if we got our hands on Palestine, we were going to use it as a buffer state to protect the Suez Canal and also as a route for the for an oil pipeline from Mesopotamia running to Haifa. And we would need to put settlers there, like we did traditionally in our colonies.

The problem was that Palestine was a very poor place that didn’t hold out a lot of prospect of garnering resources for settlers. And so very few British people would want to go there.

But the Zionists were very, very keen to go there, which suited our plans as we believed Jewish settlers in Palestine would produce a population which was more sympathetic to Britain and grateful to it, than the native Arab.

So we encouraged the Zionist project and settling Jews in Palestine suited our interests too.

There’s another reason which I’ll just put in here, which I came across encapsulated in a wonderful quote describing why David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister at the time, supported the idea of a Zionist homeland in Palestine. Here Herbert Asquith, previous Prime Minister, states that, “of course he [Lloyd George] doesn’t give a damn about the Jews, their past or their future, but he does not want the Holy Land to pass to the agnostic, atheistic French’. One in the eye for the French was the other reason that we supported the Homeland.

By the time it came for Balfour to actually produce the declaration it is quite clear therefore that the motives – and hence the foundations – were absolutely rotten to the core. And rotten foundations are good reason alone to topple the edifice.

Many people thought it would actually be toppled before the end of the war. But the the declaration refused to crack despite attempts to break it – and it held on intact primarily because the lobbying and the British self-interests were simply so strong.

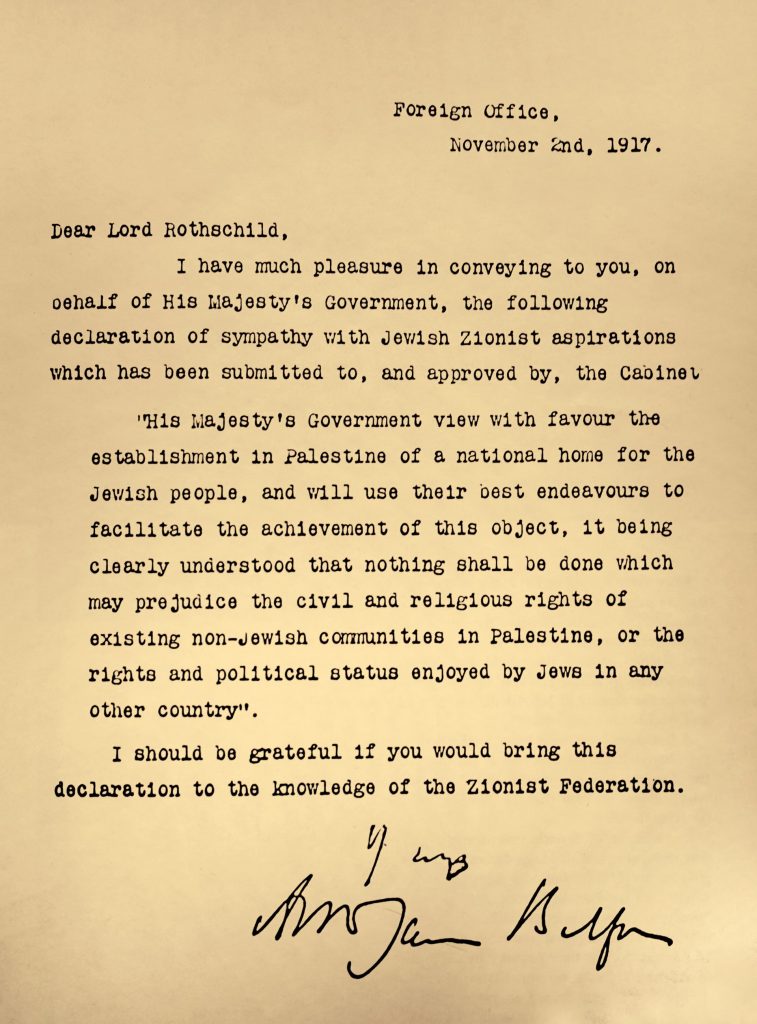

But let’s look at the actual words.

The Declaration was written to Lord Rothschild. It also has to be said that this declaration was to a large extent drafted by Zionists, Herbert Samuel and co. The phrasing has been analysed many, many times before, and I’m sure anybody who’s taken any interest has read it and studied it. But I’d just like to point out a couple of things.

First of all, before we even start looking at it, we have to be aware that at that time, 1917, November 2nd, (happens to be my birthday) the Jews in Palestine still only constituted 8% of the population. 92% were Arabs. They owned, by that time, 2% of the land. It’s very important to keep those figures in mind, to see how extraordinarily unjust this whole idea was.

So let’s look at the words. ‘His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate achievement of this object.’

So we can see that these opening words, regarding the Jewish national home, are very positive, with very active verbs. ‘viewing with favour,’ and “best endeavours” etcetera.

When it comes to the Palestinian side, i.e. the 98 % population, first of all, the term Palestinians is not used as a word at all. It being clearly understood that ‘nothing shall be done, which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’ (so the Palestinians are the ‘non Jewish communities) ‘or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.’

The Palestinian political and national rights aren’t even mentioned here. Again, remember, we’re talking about 92% of the population. As my friend Dr Salman Abu Sitta, who is possibly the most valiant warrior on behalf of Palestinians, from the point of view of the narrative war -his maps should be consulted by anybody who is looking into the history of this conflict – points out, when this declaration was issued, not only was it unjust, but Balfour had absolutely no right to even consider such a thing. We weren’t even occupying the country at that time. We hadn’t yet won the war.

In any event, not only is the Declaration built on rocky foundations, and tilted towards a gross injustice towards the majority Palestinians, it doesn’t even make sense. What exactly is a “national home”? What does that mean? Does it mean a state? Does it mean a small community somewhere? We don’t know what it means. Given the pure unworkability of it, you’d think it would have all folded and gone away before the end of the war. And many still hoped it would, including also many Jews – not in Britain, but also in America.

But already very strong steel girders were being put in under this edifice of a declaration by the Zionist lobby in the form of plans and funded arrangements for Zionist institutions of state. The Zionists were already purchasing more land. For example, Chaim Weizmann had already been out to Palestine in 1918, just after the end of the war, and celebrated there the purchase of a huge swathe of very fertile land in the north of Palestine, which was going to be used for Zionist colonies. And he a toured few “malaria-infested” Arab villages on that land, which he didn’t think would take too long to get rid of.

So now the Declaration had been decided on, what did the Palestinians themselves think of it? Indeed, when and how did they even get to hear about it? Balfour had refused to consult them on it, deliberately as he knew they’d say “no”. The question of when they heard about it is one I’ve only started asking recently, but it seems, as I discovered in the British files, that the Balfour and his supporters were only too well aware that the declaration was itself dynamite – because they ruled it be kept it secret from the Arabs.

And not only were the Arabs not to be told about the existence of this Declaration before the end of the war at the very earliest, but nor were the British military forces in the Middle East, because if they knew about it, they too would probably object, not least because promises were being made, as we know, to the Arabs that they’d have an Arab kingdom.

It must be kept secret because it is “too dangerous” came an edict from on high in Whitehall. I mean, this word “dangerous” is actually used – but of course Balfour’s people couldn’t keep it secret for long, especially since soon after victorious Allenby walked into Jerusalem. And before very long, we started debating publically how the declaration would be incorporated into the League of Nations Mandate which would define British rule.

So eventually of course, the text got into the Palestinian press – which luckily had started up by then and was shouting and arguing against the atrocious injustice which was how they saw the Declaration from the start. And although 99% of Palestinians, particularly the peasants, were illiterate, newspapers like Fallastin were read out in the village cafes; often one single paper would be read out to up to 50 villagers at one time and as they heard the words of the Declaration, probably not until early 1921, they were, by all accounts, simply stunned. My sense is that the peasant populations’ first reaction was not so much anger as utter amazement. What on earth did it mean? How can they build a homeland in our land? I mean, it made no sense.

And if they were puzzled, then they were in very good company because actually by that time, half the British cabinet and most of the foreign office were also very puzzled by what it meant. For example, Lord Curzon, not exactly an anti-imperialist, couldn’t make head nor tail of the Balfour Declaration and thought it was a disaster. So he says, ‘what does this homeland mean? I grabbed my dictionary. I see it could mean a state. This could give rise to great unease by the non-Jews.’ So he’s really warning about this, and Curson sends this warning to Balfour himself. Balfour, apparently, didn’t seem to know what it meant either. This is stunning. Balfour replies to Curzon, something along the lines of, “Really? That’s not how I understood it at all. If the Zionists think this means a state, that’s definitely unacceptable.’

Even Balfour didn’t realise that the Zionists were going to interpret this as meaning a state, or if he did realise it, he was covering up.

As always with this kind of research, when I was reading through the documents, the most interesting and the most enlightening comments are often the comments in the side-lines of the official papers, notes scrawled by middle ranking officials who give their views and all the way through, they are exclaiming with extreme anxiety about the implications of this document. How on earth they, and people like them down the line, are going to implement the Declaration, they ask?

It’s going to be impossible to reconcile this extraordinary idea of building a homeland for this tiny minority of Zionists in Palestine, where still about 90% of the people who live there are Palestinians. These officials even warn of bloodshed as early as 1920. But they also know there’s no going back as the Zionist lobby will not give up.

The holes in the Declaration become even more exposed as the terms of the Mandate itself are negotiated because self-determination for other new emerging states is said to be the order of the day, in a brave new post war world order.

And we’re going to give self-determination to the other countries under other British mandates. But apparently not to the Palestinians. How do we justify that?

Well, we don’t really try very hard is the answer. And what we do is we then produce the keys that the Zionists needed and wanted if they were to do the thing they yearn to do -which is to create that apparently impossible Jewish majority in Palestine. And those keys we gave them as British rule began were twofold and very simple. We permitted Jewish immigration into Palestine at a large scale, and we made it much, much easier for the Zionists to buy Arab land. Both these things had been difficult under the Ottoman Empire, the Sultan having tried to control both. But as soon as Britain took over we opened both immigration and land purchasing up and the Zionists exploited those opportunities to the hilt.

The immigrants started coming in, in steamers to Jaffa, and the land sales increased immediately.

Now, of course, the Palestinians did see precisely what the Balfour Declaration meant. They saw the people coming off the boats in Jaffa, and in those early years they they saw a lot of Bolsheviks arriving. They saw people that didn’t even look like the Europeans that they knew to date. Within a year or so of the Mandate beginning the Palestinians saw an entirely new scale and type of Zionist who was not only moving in amongst them and building colonies near them, but who appeared – as certainly the Bolsheviks did – to be an affront to Islam itself. They were dressed immodestly; they were swimming naked. All sorts of stories were soon swirling around about these alien foreigners who were now parading in the streets of Jaffa with communist banners.

So we soon had the first riot, not surprisingly. The bloodshed didn’t take long to start spilling. The first riot was in Jerusalem in 1920, and it triggered the first Royal Commission of Inquiry held by a major general called Phillip Palin, who held a perfectly good inquiry, listened to evidence of what caused the riot, and concluded that now – having seen attempts to put it into practise on the ground – the Balfour Declaration was a construct that couldn’t work. Palin’s report was simply shoved on one side and suppressed for many decades.

But then, not long after, an even worse riot happened in Jaffa. The scene was really almost absurd. If you read the details of it. You have Bolsheviks coming off the steamers, walking through these narrow Arab streets in Jaffa with their banners. We have the Arabs with sticks, trying to fight them. And then the flare up spreads out to the villages and we have the British, desperately trying to control the situation with the Indian Cavalry charging through the olive groves, with terrible bloodshed; and an uprising which cannot be matched for both farce and tragedy as the Brits for the first time and certainly not the last, totally lose control.

Then of course we have the second Royal Commission of Inquiry by another good man, Sir Thomas Haycraft, then chief justice. And I do recommend that if you’re interested, you read Haycraft’s report because it’s brilliantly written, very fair, very colourful and very sad report. But at the end of it, Haycraft also concludes that the Balfour Declaration, I mean, he doesn’t say this in so many words, but this is what the meaning is, that it won’t work. He listens carefully to the Zionists claim that the riots aren’t a serious threat they are just provoked by a few Arab agitators, a line they are now pressing as they are clearly terrified the British might drop the whole idea, so much trouble is it giving. The fellaheen, the peasants, are not really against the Zionists say the Zionist lawyers, but Haycraft doesn’t agree. He says that their fears are genuine because he’s listened to the Arabs too. In fact, Haycraft is probably the first British adjudicator to listen properly and fairly to the Arab case – and possibly the last.

But this British Commission of Inquiry is also ignored, its report set on one side and we roll on regardless, Declaration still intact. Meanwhile, Herbert Samuel has taken over as High Commissioner and unrest dies down for a few years, partly because Herbert Samuel is actually a sensible man in many ways. And he has realised that this Jewish homeland plan, which he partly instigated, is not necessarily going to work as easily as he might’ve once thought. And so Samuel imposes some limits on immigration, which quietens things down a bit, meanwhile a new line is issuing from the Zionists to help the British Colonial Office and its new Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, stick with the plan. And this line says that Zionism will be good -not only for the Jews in Palestine -but for the Arabs too. Zionist energy and excellence and ability to drain the swamps will trickle down to the Arab native, improving their lives too. But when Churchill passes through Gaza on a train in 1921, he is booed. “Balfour Down” they cried.

In fact, this argument that Zionism helps all becomes the only remaining way the British can rationalise their on-going commitment to Balfour’s plan and for some years they hang on to the justification for dear life.

But very soon it becomes quite obvious that the benefits of Zionism are not trickling down to the natives – it isn’t happening, By, say, 1925/26 British district officials. who are again these middle- ranking officers sent out now to mend the holes in this whole affair, are going around Palestine observing how the villages are becoming poorer and poorer, and the peasants are now so in debt to moneylenders they can barely feed themselves and are having to sell more and more of their land. And the reason is that while the Zionists are certainly embedding themselves on the land with energy and enterprise, they are doing what they are doing entirely separately from the natives. They’re not employing Arabs. They are building separate colonies. They are building separate institutions. They don’t want to, nor are they’re attempting to actually help the Palestinian Arabs, except for one exception, which is that they put doctors in some of these colonies. And the Jewish doctors do work in the Arab villages, helping them cure eye diseases, helping them kill malaria and so on. And these individual Jewish doctors, are no doubt entirely altruistic, but one has to ask also to what extent the Zionist leadership encouraged them to go out and heal the Arabs because they didn’t want infections to cross-infect into the settlements. I have seen Zionist correspondence suggesting that the placing of jewish doctors in the colonies was part of a wider plan to pacify Arab peasant unease about their settler neighbours thereby enabling settlements to expand and buy land without hindrance.

But no doctor or anyone else for that matter could heal the terrible poverty – starvation even – that was spreading through the Palestinian countryside by the late 1920s, as more and more of the Fellahin were becoming “landless” and no longer able to farm enough to feed themselves. In the north, thousands of these landless farmers were flocking to Haifa where they became followers of a charismatic preacher, called Izzedin al Qassam.

By the late twenties British officials are warning loudly of the danger created by the growing number of these “landless Arabs” and their analysis clearly points the finger of blame at the founding Balfour Declaration which gave unjust preference to Zionist colonisation and did so little to support the Palestinian village farmer.

The British enterprise of Palestine, with its Jewish Homeland is also costing the British Treasury dear because the landless Arab is incapable of paying taxes. Whereas in other colonies, traditional colonies, the landless natives at least worked on settler plantations, this is not happening in Palestine and the landless Arabs are become restless again.

In 1929, the biggest riot so far breaks out, this time in Jerusalem, Sir John Chancellor, the hapless Consul General at the time had just gone on holiday when the riot broke out and on return discovered the chaos had spread out from Jerusalem to the the towns of Nablus, Hebron, Safed and Nazareth as well as the villages. Chancellor’s first instinct was to come down on the rioters on both sides like a ton of bricks, with hundreds of Arabs in particular rounded up, locked up, and scores executed.

But as the result of yet more Commissions of Inquiry which exposed again the impoverishment and collapsing way of life of the Fellahin, Chancellor seems to see the light, proposing an entire reversal of many of the Mandate regulations in order to support the Palestine farmers, curtail Jewish immigration and land sales. Without such changes, he and others now asked – how will these Palestinian farmers who cannot farm and cannot work survive? Where are they to go?

So Chancellor becomes probably the last person in the British government who has a chance to reverse some of the worst failings of the Balfour Declaration. He sees the sense of giving the Arabs at least a chance to get their own independence, to build up their own political and national rights. He even puts his name to a White Paper which goes to the House of Commons and appears to be going through. At the last minute, however, the apparently irresistible lobbying from the Zionists in London builds up to a new pitch and this last- chance White Paper is defeated.

Next time there’s a riot it is a full scale pan-Palestinian uprising, spurred on in its early days by the Haifa preacher, Izzedin al Qassam. The uprising soon became known as the Arab Revolt of 1936 and lasts nearly 3 years. This time the British authorities didn’t even try to address the root causes of the uprising. Instead they chose another more traditional method of dealing with the natives, well-honed across the Empire over the years. A man called Orde Wingate was brought in – with his night squads and his house demolition squads – and given full powers to simply crush the uprising.

I saw this week, that Palestinan rights activists have slapped a demolition order on the statue of Orde Wingate, which is somewhere down in Westminster. I must say, I don’t think any Palestinian will be sorry to see his statue toppled, given there is no opportunity to see Balfour crashing down.

At this point of my talk, I think I can safely say – the rest is history. In fact, I haven’t even mentioned the Nakba because by the time we get to 1948 and the war, which followed the decision to partition Palestine, the Brits have already given up on Balfour and what it tried to achieve; and the entire edifice of the Mandate is in state of collapse, British forces in Palestine running away leaving the Arabs and Jews to fight it out. We know which side came off best.

On recognising at last that the Declaration was a catastrophe, we had handed the whole mess over to the United Nations, who came up with their own ideas for partition which don’t go down at all well. By 1947, the Palestinians still represent by far the majority of the population, and still own by far the majority of the land. In fact, despite their best efforts, the Zionists still own only 6% of the land in 1948. So therefore naturally the Palestinians reject UN partition plans which offer them less than half.

What happens next, as we know, was the war of 1948. And under the cover of this war, the Zionists basically erase more than 450 Arab villages, including 200 in the district of Gaza alone, the residents of which, as refugees, are still in the Gaza Strip today.

In view of my account of these events, you will no doubt not be surprised to hear that in my opinion lacking a statue – at least the Balfour edifice, which is the Declaration, should indeed be toppled.

Nevertheless, I’d just like to conclude by asking whether events since Balfour died, which after all was in 1930, should also be laid at his door? I think not.

Why has the world not since corrected -put right, tried to equalise, at least, – the balance of rights – Arab and Jew- in Palestine-Israel since then?

Of course, there have been attempts. We know that. Many attempts at peace. But still more than 100 years after the Declaration, Palestinian lives, don’t appear to matter as much as Jewish lives when you look at the tragic situation in which the Palestinians now live.

And this bring me to the comparison I started out with between Palestinian Lives and Black Lives. I believe that in some ways Palestinian lives today seem to matter even less even than Black lives. The reason is this.

Although we know that Black Lives today have still not achieved equality, at least past crimes committed against them – most obviously slavery – are acknowledged and accepted as crimes. The root cause of the injustice against Black Lives is largely known and faced up to.

But in the case of the Palestinians, the outside world has not even come to a consensus on what the root cause of the injustice against them was. Though some of us take no convincing, the world is nowhere near accepting that the root cause of the Palestinian conflict was the colonial settlement on Palestinian land, aided by the British. Indeed, many inside Israel and in the world beyond Israel would dispute any such claim, offering an entirely different – and, in my view – historically inaccurate narrative.

Moreover, most today accept that slavery is a concept entirely abhorrent in the context of values of the modern era. Yet many would still dispute that the erasing of Palestinian villagers and expulsion of Palestinians as refugees in 1948 even happened, and cannot bring themselves to see that it is as abhorrent and alien to the values of today’s world as slavery itself.

Protests have broken out in recent days in Balfour Street, in Jerusalem as Israelis rise up in anger against their corrupt Prime Minister, and there is some hope to be drawn from these protests because amongst these Israeli activitists are some who shout that Palestinian Lives matter and who are clearly trying to turn the narrative around. But who is listening?

Not many politicians in the United Kingdom. In fact, it is depressing to conclude that even if there were a statue to Arthur Balfour on our streets, we would be nowhere near to toppling it as the wrongs he committed are not even yet recognised here as wrong. Theresa May could not bring herself to apologise to the Palestinian people on the anniversary in 2017, as my friends in Gaza took every chance to reminded me when I visited them at that time.

Perhaps, therefore, instead of toppling a statue we could at least begin to think about rewriting the declaration and therefore the narrative.

And to that end, I would like finally to propose a text. We might say, for example, that her Majesty’s government favours the establishment of one democratic state for all its citizens, Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs, all living in peace.

So with that thought in mind, I’ll leave you open to questions.

Diana: Thank you so much, Sarah. That was really interesting. And we’ve had so many questions come in and we’re going to try to get through as many as possible, because there’s so many. One thing I will say, there’s been a lot of people asking about things like the Peel Commission, McMahon Correspondence, Chaim Weizmann, etc. We cover these quite extensively in past talks. So I really recommend if you’re interested in those kinds of topics that have a little look at our recordings section, because we’ve got our previous audio and video recordings and transcripts of our past events where we covered these extensively.

When you were talking about your book about Gaza and we had a question from Johnnie Byrne, are you interviewing people in Gaza? And how do you manage to travel there?

Sarah:

It’s a good question. Of course, as you know, it’s very, very difficult to get into Gaza. Now, there are controls on everybody going in, including foreigners. Recently, by the way, with the coronavirus, it’s just impossible. But before the coronavirus came out, the Israelis control all exits and entrances through Erez, which is the only checkpoint into Israel the Egyptians control and trances and exits into Egypt, at Raffah. But for someone like me, the only way to get in is to go in as a foreign correspondent, which is what I do. By the way, all Israeli journalists are banned, all Israelis period are banned from going to Gaza. It’s important to remember that because the Israelis are really forgotten what Gaza is, what it looks like, what they wonder what people in Gaza, who they are. We are allowed in, but only under very, very stringent conditions. I have to prove all sorts of things. I have to be sponsored by a newspaper. I have to show that I’m currently writing. I have to give them examples of my work. And I have to tell you, I was banned myself in 2018. And we had to appeal against it, and I actually won the appeal.

But I turn up at Erez checkpoint and I go through this extraordinary really surreal checkpoint where there’s almost nobody there. Usually often I find I’m the only person there, and when you get through the checkpoint, there’s a little door that says ‘Gaza’ and you press the door and it doesn’t open. Kafkaesque doesn’t even begin to describe

And you finally get through, and there’s this extraordinary sort of cage that you have to walk through all the way out, across no man’s land, basically, which seems to get longer and longer. And there are these wonderful goats that are sort of around that come and nuzzle up against the cage. And then you get all the litter because of course the people of Gaza are far away still, far up at the other end of this cage

But you know, they are there because the crisp packets and cans are blowing all around. Its surreal.

Diana:

We’ve got a couple of questions that are coming in advance, for example, from Alfredo Roldan Flores, who has emailed in advance and some other people have asked questions as well, about one-state two-state, always topical. Alfredo says, is it a mask that has provided Israel with the perfect cover to annex daily, et cetera, et cetera?

Sarah:

I was a reporter out in Jerusalem during the Oslo period. I covered the Oslo and the two-state, the beginnings of that whole process. At that time, there were various views on this. There were those who were always against a two-state solution, always thought it was a sell out by Arafat and the Palestinians, because as I kind of touched on in my talk, it meant giving up half of the Palestinian land which they thought they shouldn’t have had to give up in the first place. On the other hand, it seemed to offer the possibility of at least a kind of self-respecting state or something to start with. And I never quite knew which side I stood on until I went to Gaza actually on the day that they signed the peace agreement, Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat on the White House lawn.

I was in Gaza that day. It was quite extraordinary. So they signed the thing at midday and the morning started off in Gaza with tyres, burning and black flags everywhere, and Hamas flags out there. And you felt this, this doesn’t have a good feel. But the minute that handshake took place, and I watched it on a television to being in a cafe in Gaza city, the whole place burst out with Palestinian flags flying and children laughing and parties, and doves of peace appeared on the walls in Gaza. And it was the most euphoric moment I think I ever experienced in my life, they wanted peace. And also, remember the Israeli soldiers were still in occupation at that time, there were still Israeli feet on the ground in Gaza. They were watching all this. And I remember going up to an Israeli soldier and saying, ‘what do you think about this? You know, these are pretty happy people now.’ And I said, ‘are you in favour of this deal?’ He said, ‘well, it looks like they want peace. If they want peace, that’s good. We can go with it.’ So that there is this desire on the Israeli side for peace.

That all fell apart, as we know, for all sorts of reasons, it would take too long to discuss. And I now think we’ve moved beyond that. I don’t think there’s any going back to that. I didn’t go to back to Palestine for many years, during which this all changed. When I went back, young Palestinians were not talking about anything two-state, it was old, it was history. They were talking about 1948 lands. They want to go back to their 48 lands. They were remembering their villages, the whole history of pre-1948 and the Gaza district. It just was much, much more in the mind that it had been when I was there. Because under Oslo, it was 1967 people were talking about, but that had been basically undermined by the failings. And now the answer had to be to return to 1948.

But I also believe strongly that if the Israelis say this is impossible, because this means we can’t have a Jewish state, this means we can’t live a Jewish homeland, and the Arabs hate us, I ask them, I say, ‘what do you think about what’s wrong with the one-state? You go on the light railway in Jerusalem. There are Arabs, there are Jews, you are working together. Some of get on pretty well together. What’s the problem?’ Diana here, I am sure she mixes with Jews in London. I mean, what is the problem?

The answer comes back, ‘it’ll never happen because that will mean we have to not have our Jewish state number one. And number two, because the Arabs hate us.’

I actually don’t think that the Arabs do hate the Jews in that sense at all. I think with a huge underpinning and huge support, I believe it’s the only way, but it’s a heck of a long way.

Diana:

Noru Tsalic asks about the Ottoman empire and why we’re focusing on European colonialism and imperialism and not the Ottoman. I would just like to say that we don’t have time to cover the whole entire history of the world in one hour. So that’s partly why. But do you have anything you want to touch on with regards to that, he says the Ottomans (centred on Istanbul on the edges of Europe) tended to look west, not east. They generally despised the Arabs, ruled them via corrupt and incompetent governors and in general, neglected the place. Any comments on that?

Sarah:

Yes I think it is true that, in the periods that I know about anyway, which is the later part of the 19th

Century, the Ottoman Empire was in a really bad way. It was to be short of money. It was having trouble in sorts of sorts of areas and wars and the Balkans were uprising and so on. And they largely had left the Palestinians be just to get on with their own lives. And that’s partly why they became so cut off and so dependent on themselves. And the peasant farmers were not interfered with very much, except they had to pay Ottoman taxes, of course. And also they were exploited for that. And the Sultan didn’t do a great deal for them, but he was very interested though, in the Palestinians. He’s got a wonderful photograph album of amazing Palestinian scenes during the Ottoman period. And he did try to protect them against the Zionist colonisation in the early years, because he could see, not because he was in any way, anti-Jewish, as far as I can tell, but because he knew this was going to cause problems.

He didn’t want another problem like he had in the Balkans. He wanted to keep Palestine quiet. So he tried to control Jewish immigration, but he failed because of what I was talking about with the European presence, the European Consuls who had their own powers outside Ottoman law, who let immigrants come in around the back.

I don’t know a great deal about the wider Ottoman Empire. I’m certainly not the expert to talk to. There are many others who are. I could just talk a little bit about Palestinians of that period. I don’t think that the Ottoman Empire treated the Palestinian peasants particularly well. On the other hand, the Ottoman Empire was crumbling. It was coming to an end. It was on its last leg. So I can’t say much more than that.

Diana:

Well following on from that David Wetton has said that ‘Britain had already promised the Arabs independence from the Ottoman empire in the 1915 Hussein- McMahon Correspondence. The British had also promised the French in a separate treaty known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement that the majority of Palestine would be under international and administration while the rest of the region would be split between the two colonial powers after the war. How did Balfour justify ignoring these previous promises through his declaration?’

Sarah:

The answer to that is he didn’t justify it. He just got on with it and did it. It’s quite stunning. That’s why I mentioned that it was so interesting when I discovered that they decided to keep the Balfour Declaration secret. I mentioned particularly including from the British forces in the Middle East, people working on the Allenby. I’m sure Allenby knew about it. He didn’t like it by the way. But they kept it secret from the Arabs as well, partly because they knew about this promise and the McMahon Correspondence and all the rest of it, and the deals that were done with Faisal to give them the Arab kingdom. The arrogance of these guys is stunning. They just did what they felt they wanted to do and got on with it. They just undermined all of that. And the betrayal was done. And they went down to the club in Pall Mall and said, ‘it’s all for the good of the Empire, old chap.’ I don’t think there’s a more subtle explanation than that.

Diana:

You mentioned that the Balfour Declaration, they aimed to keep it a secret to avoid any kind of resistance. John Quigley asked the Balfour Declaration was published a few days later in The Times. Does anyone know how the times got it? Did the war cabinet want it published? Was it leaked by someone? Do you have any insight into that?

Sarah:

I have no idea about that. I suspect that it was probably the Zionist movement that had it published. Of course it suited them to show that they were moving on. It helped them getting support from others, Zionists around the world, in America and so on and get money flowing in.

If it was published in The Times that soon after you might also want to ask, how on earth did they manage to keep it secret from the Arabs in Palestine from the British in the Middle East?

The answer that is, you know, it’s quite astonishing that with the internet and the whole world we live in, and here we are in a Zoom meeting, but these places were so cut off.

Communication was so limited, especially during war. Of course the people in the leaders in Jerusalem and Jaffa would have learned a much earlier, but the ordinary Palestinians, they literally were living in their own world. They didn’t know what was going on. They had no means of finding out, there were no newspapers during the war. There was no communication to the world that the Ottomans were fighting all around them. So they didn’t know. So it wasn’t so hard to keep it from them. But in terms of something appearing in The Times, I would say almost certainly that would have been leaked by probably Herbert Samuel or Weizmann or one of these powerful Jewish figures in London at the time who saw it was in their interest to leak it.

Diana:

Thanks for that. I have a question from Magan. What was the response of the Palestinian ( 2%) at that time -1925 onwards?

Sarah:

It is interesting you say Palestinian Jews. The Arabs talk about a group called Jewish Palestinians, who were the Jews who lived in Palestine in a settled fashion and had done for hundreds of years before the actual Zionists turned up. So just to distinguish them, they lived as Ottoman citizens by the way, and, and lived quite at ease with their Arab neighbours.

I haven’t heard them called Palestinian Jews before, but anyway, I know what you mean. So their reaction was they were absolutely over the moon course. They were over the moon. This gave them the chance they needed. This gave them the chance to actually legally bring immigrants, to legally buy land.

And also those who were thinking of coming were celebrating too. So for example, I’ve read that in the synagogues all across Southern Russia, the minute the Balfour Declaration, that certainly wasn’t kept secret from them, because again, we needed them to know in order for money to come in and for immigrants to start booking their tickets from Odessa, steamers to Jaffa. So they were celebrating, no, they thought it was great.

They started getting less supportive when they realised that the Brits were beginning to back off a bit. So as the Brits back off a little bit, like beginning to control immigration a little bit later in the twenties because of the Arab riots, then the Zionists say, hang on, what are you doing? So, but during the first days, they were over the moon.

Diana:

Only I’m going to ask you one last question, because we’re coming up to the end of our time. This one’s from Gillian Mosely. When you discuss early Zionists, are you referring to all of the Jews who migrated to Palestine, also, including those who had been in situ for quite some time? What approximate date are you suggesting this actually started, i.e. can we have a clarified timeline please?

Sarah:

My research suggests, and I think I’m right, that the first Zionist settlement was called Petah Tikva and it was built on top of the first erased Palestinian village. It was called Mullabes, it’s quite near to Jaffa. And the settlers arrived in 1878. The contest over that piece of land and that settlement continued for some years, but it began in 1878. And then in the 1880s, about four or five new colonies were placed around the area. For example, a little bit further south, Rehovot was put on top of Diran and there were others. These were all settlements that were placed in Palestine, in the 1880s and early 1890s.

Diana:

Well, Sarah, with come up to our end of to the end of our time. I just want to thank everyone who came along to listen. I hope you found it as fascinating as I did. And Sarah, thank you so much on behalf of the Balfour Project for coming along and doing this talk, it was super fascinating.