Book Review: Palestine the Reality by J.M.N. Jeffries

By John McHugo

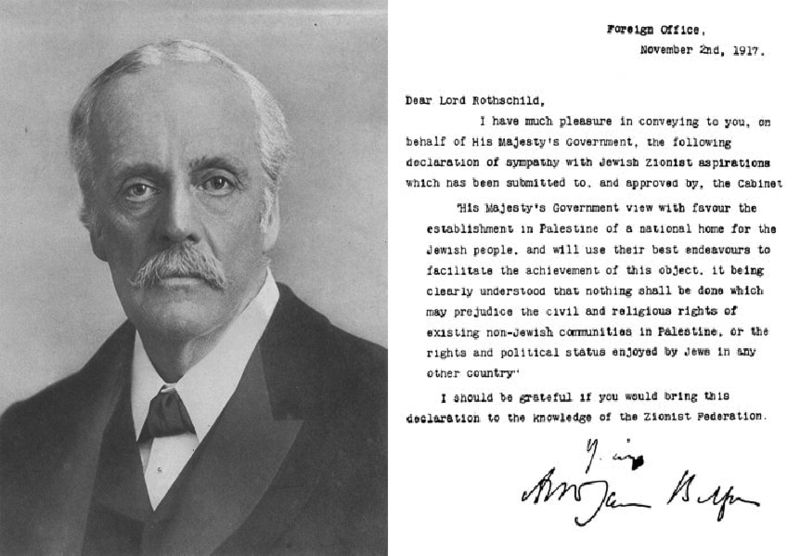

Many people trying to get to grips with the Israel/Palestine conflict begin with the First World War and the contradictory promises Britain made at that time. These were pledges to the Arab nationalists (the Hussein-McMahon correspondence), to France (the Sykes-Picot agreement), to the Zionist movement (the Balfour Declaration), and the little known Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918 promising “the complete and definite emancipation of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks” .

Fromkin and Schneer

There are a number of assiduously researched and well written books currently on sale which aim to enlighten the reading public about these promises and their problematic aftermath. Two of the best known and most influential are Jonathan Schneer’s The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab Israeli Conflict (2010),  and David Fromkin’s

and David Fromkin’s  A Peace to end all Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (1989).

A Peace to end all Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (1989).

Both scholars show the perfidy of the British politicians and officials who were desperately trying to co-opt allies in the grand struggle against Germany and its Ottoman ally. That perfidy lies at the root of much of today’s instability in the Middle East. As Schneer eloquently puts it, they were sowing dragons’ teeth.

Jeffries the Daily Mail’s star reporter

Unlawful in issue, arbitrary in purpose, and deceitful in wording the Balfour Declaration is the most discreditable document to which a British Government has set its hand within memory

Yet there is one crucial name missing from the formidable bibliographies at the back of these two works. That name is J.M.N. Jeffries, whose book Palestine: The Reality appeared in 1939 but was largely forgotten soon afterwards. This may have been because most stocks of the book were destroyed in the Blitz. Jeffries was a respected war correspondent for The Daily Mail during the First World War. Afterwards he sometimes reported from Palestine, while at other times he devoted his formidable skills as an investigative journalist to uncovering the history of the drafting of the Balfour Declaration, the negotiation of its text between the British Government and the Zionist movement, and the way it was subsequently implemented in Palestine by British officials in cooperation with the Zionists. His concern was always to put before English-speaking public opinion the case of that “small, wronged country” called Palestine.

Today, his clear, classical prose can hit us straight between the eyes:

“Unlawful in issue, arbitrary in purpose, and deceitful in wording the Balfour Declaration is the most discreditable document to which a British Government has set its hand within memory.”

True objectivity

The charges behind Jeffries’ rhetoric need to be taken seriously. I believe he sustains them, and would urge people who are sceptical to read what he has to say before they judge. Because he made his sympathies plain, he was sometimes accused of a lack of objectivity but I do not think he can be faulted if you examine the intellectual integrity of the arguments contained in his book.

True objectivity does not consist in setting out opposing viewpoints with a kind of studied neutrality, then failing to draw whatever fair minded conclusions ought to be deduced from the evidence assessed.

Jeffries had a keen, logical mind, a devastating pen, an ability to use the full range of the English language, and a passion for justice and to establish the truth. He does not hold back. He also had another quality rare in historians of the Arab-Israeli dispute: a good grasp of the relevant areas of international law.

Pulling Punches

The group that transcribed the text from the last complete copy in the British Library are to be congratulated for returning Jeffries to the full light of day after eighty years of obscurity, as are Skyscraper Publications for producing the new paperback edition. Now that Palestine: The Reality has at long last been reissued, it is interesting to compare it with the works of Fromkin and Schneer. In contrast to Jeffries, a reader senses that these two writers sometimes pull their punches. Each, for instance, avoids going into the nitty-gritty of what Britain did (or did not) promise “the Arabs” in the Hussein-McMahon correspondence. Instead, they merely inform the reader – quite correctly, so far as it goes – that pro-Arab writers have claimed the promises in question included Arab sovereignty over Palestine, while pro-Zionist writers argue the opposite. Schneer even states quite baldly that “I have no intention of entering, yet alone attempting to settle” this argument. Compare this to the approach Jeffries takes. He prints the text of the letters for the reader to make up his or her own mind. He shows how the correspondence developed, and explains the terminology used and the discrepancies between the English and Arabic versions of the texts.

Palestine most certainly was included in the area claimed as Arab by the Sharif Hussein and was not excluded by McMahon

His argument is all the more powerful because he was also able to interview important participants in the story, such as Herbert Asquith (British prime minister at the time) and Sir Edward Grey (his foreign secretary) – something that was, of course, impossible for Fromkin and Schneer. He uses his logical and forensic skills to establish the true meaning and significance of the letters. His conclusion is that Palestine most certainly was included in the area claimed as Arab by the Sharif Hussein and was not excluded by McMahon. This meant that Britain’s attempt to argue the contrary was extreme bad faith.

Jeffries knew what he was doing. The British government did its utmost to keep the letters secret, but he caused consternation in Whitehall with a major journalistic scoop when he persuaded The Daily Mail to publish them. This led to Britain’s contradictory promises to “the Arabs”, “the French”, and “the Jews” coming under the spotlight of a debate in Parliament.

Schneer’s dragons’ teeth

Why does all this matter now? The rights of Israel and Palestine and their peoples today stem from international law, not from what a British High-Commissioner in Cairo promised in 1915-6 or Arthur Balfour put in his letter to Lord Rothschild in 1917. Yet Schneer’s dragons’ teeth are still springing up all over the Middle East. If we are to extract them, we cannot just look on the rights denied to the Palestinians as “unfinished business” – to use Theresa May’s infelicitous reference in the speech she gave to commemorate the centenary of the Balfour Declaration. We need to face up to the past with all its warts, and this includes the shameful aspects of Britain’s role in Palestine.

This is why Jeffries’ book is so important. Palestine: The Reality is written with a painstaking, at times almost obsessive, attention to detail. It covers the contradictory promises and their background, Britain’s administration of Palestine as an occupying power up to 1923, the genesis of the mandate itself, and the way Britain conceived its responsibilities in Palestine up to the finalisation of the book in 1938. Matters such as the drafting of the relevant portions of the Covenant of the League of Nations, Britain’s grant of the Rutenberg concession, the conclusions reached by British official enquiries into events in Palestine (going up to the Peel Report and its abandonment), the steadfast refusal throughout the whole of the mandate to give the Palestinians genuinely representative institutions (in contrast to neighbouring countries under British domination), the subjection of all Jews in Palestine to Zionist control (which many of them did not want) – all these topics are covered. He witnessed with his own eyes the betrayal of the Palestinian people. That betrayal played a major role in the frustration of moderate, liberal Arab nationalism. This led in turn, a few decades after Jeffries’ death in 1960, to the anger of the Jihadis with which we are now all too familiar.

Britain’s policies were illegal

Jeffries argues cogently that the Balfour Declaration was used illegally by British officials as their guiding star when establishing and enforcing their rule in Palestine – both before and during the mandate. This betrayed the “sacred trust of civilisation” that Britain undertook towards the Palestinian people to guide them to independence. The book contains much information to suggest that Britain never intended to fulfil its obligations towards the Palestinians, and that the leaders of the Zionist movement never accepted the legitimacy of Arab aspirations (for someone writing today, this cannot fail to bring to mind Israel’s new ‘Nation State Law’). Turning to international law issues, Jeffries shows that Britain’s policies in Palestine which favoured the Zionist movement broke the provisions of the 1907 Hague Regulations during the period 1917-1923 while Britain was the occupying power. These policies then became illegal under Articles 20 and 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations once the mandate began. Presciently, he suggested that this bad British example, this failure to uphold the Covenant in its early days, would lead to the League’s collapse.

British officials as their guiding star when establishing and enforcing their rule in Palestine – both before and during the mandate. This betrayed the “sacred trust of civilisation” that Britain undertook towards the Palestinian people to guide them to independence. The book contains much information to suggest that Britain never intended to fulfil its obligations towards the Palestinians, and that the leaders of the Zionist movement never accepted the legitimacy of Arab aspirations (for someone writing today, this cannot fail to bring to mind Israel’s new ‘Nation State Law’). Turning to international law issues, Jeffries shows that Britain’s policies in Palestine which favoured the Zionist movement broke the provisions of the 1907 Hague Regulations during the period 1917-1923 while Britain was the occupying power. These policies then became illegal under Articles 20 and 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations once the mandate began. Presciently, he suggested that this bad British example, this failure to uphold the Covenant in its early days, would lead to the League’s collapse.

He cogently analyses and debunks the arguments still occasionally adduced to suggest that Prince Faisal in some way renounced Palestine as an Arab country in the document known as the Faisal-Weizmann agreement. He also covers the genesis and drafting of the Balfour Declaration and shows how what we might now call an echo chamber developed in British and American official circles that saw Palestine solely through the lens of the Declaration. Part of this was due to the far too cosy relationship which key figures in the British political establishment such as Lloyd George, Balfour and Churchill developed with Dr Weizmann and the Zionist movement. The Zionist leaders were within this echo chamber, but Arab voices were not. They were simply not consulted and were deliberately excluded from the decision making circles. The same applied to the drafting of the Palestine mandate itself. The result was that Palestine came to be seen as “a problem”. Yet it was the Balfour Declaration and British imperial policy that turned a peaceful land into a powder keg. Jeffries shows us how this happened.

The safeguard in the Balfour Declaration

Yes, the Balfour Declaration did contain a safeguard for the Arab Palestinians: the words “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”. But Jeffries points out that these were “spurious guarantees”. He draws our attention to two particular problems with this sentence that are rarely mentioned. In the first place, the wording is extremely vague, and this enabled those with power (i.e. the British politicians and officials dictating policy in London) to interpret them in whatever way they saw fit – to the disadvantage of the native Palestinians entrusted by the League of Nations to their “tutelage”.

Even worse, the phrase “existing non-Jewish communities” was inherently dishonest. To a civil servant in Whitehall, a Jewish community leader in Whitechapel, or someone reading the newspaper over breakfast at home in Tunbridge Wells, this gave the impression that there was no sense of incipient nationhood among Arabic speaking Palestinians or even that they were the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants. It was as though “there had always been in Palestine mere clumps of Arabs dotting a basic carpet of Jews”. “Existing non-Jewish communities” concealed the fact that there was an Arabic speaking community between the Mediterranean and the Jordan that comprised at least 90% of the population, and had lived on the land peacefully for many hundreds of years. At that time – in striking contrast to today – religious differences in Arab countries were generally becoming less important as a political divide. The steadily growing educated public in Palestine, Muslims and Christians alike, saw themselves as proud Arabs. They wished their land, which was about to be arbitrarily truncated by the Anglo-French partition setting up the mandates, to be part of a federal constitutional monarchy covering the whole of Arab Greater Syria. That dream was snuffed out, with consequences that are also still with us.

Colin Andersen’s Balfour in the Dock

Skyscraper have also brought out a helpful companion volume to Palestine: The Reality, a study of Jeffries by Colin Andersen. This is well worth reading. It bears the provocative title: Balfour In The Dock: J.M.N. Jeffries and the Case for the Prosecution. As Andersen puts it, “Jeffries’ real claim on the attention of posterity lies, ultimately, neither in his journalistic prowess nor on his fine prose, but on the fact that he has written the most passionate and forensic account in English of how the British went about turning innocent,  unsuspecting, [pre-First World War] Palestine into today’s ‘Palestine problem’ “.

unsuspecting, [pre-First World War] Palestine into today’s ‘Palestine problem’ “.

Whenever possible, Andersen quotes Jeffries and lets him speak for himself. He carefully points out the rare occasions on which Jeffries was confused or got something wrong. He sets out what little we know about his personal life. This seems to have been uneventful, so far as we can tell, although Andersen has managed to locate several vignettes that describe Jeffries’ physical appearance as well as showing his formidable energy and the consistency of his compulsion to uncover the truth. He traces Jeffries’ work throughout his career, beginning with some of his war reporting in 1914 and subsequently putting him in the context of Palestinian writers who were his contemporaries such as George Antonius, A.L. Tibawi and Izzat Tannous. He also includes fascinating exchanges of correspondence between Jeffries and his opponents such as Balfour’s niece, Blanche Dugdale. By quoting both sides in full, Andersen always allows readers to make up their own minds and form their own conclusions.

Like all of us, Jeffries was a person of the times in which he lived. Some of his figures of speech, imagery and allusions may now escape readers. For instance: will everyone today realise that “Gilbertian” is a reference to the kind of satire contained in the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan? He often uses the words “race” and “racial” when today we would be more likely to say “ethnicity” and “ethnic”. He took it for granted that Britain had high standards of behaviour as an actor on the international stage and in the way it governed its empire. Yet that was precisely why he found the betrayal of the Palestinians so shocking.

Historical debate should be informed by truth

If we believe that historical debate should be informed by truth, then Jeffries is a voice that now needs to be heard loud and clear. I vote Palestine: The Reality as the best book available examining the Balfour Declaration. It is to be hoped that The Daily Mail will find a suitable way to commemorate the memory of one of its greatest and most courageous journalists.

John McHugo is a trustee of the Balfour Project. His own assessment of the Balf our Declaration and the Arab-Israeli dispute can be found in his book A Concise History of the Arabs. He is also the author of Syria: A Recent History and A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi’is. johnmchugo.com

our Declaration and the Arab-Israeli dispute can be found in his book A Concise History of the Arabs. He is also the author of Syria: A Recent History and A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi’is. johnmchugo.com