A one day conference exploring the different legacies of the Balfour Declaration and how a greater understanding of history can contribute to justice and peace in the Middle East today was held in Winchester University on May 18th 2013. Over 50 people gathered in the Stripe Theatre. They represented a wide range of opinions from Jewish supporters of Israel to Palestinian activists, including two Jewish Rabbis as speakers. The Conference was a start in developing a conversation on Britain’s role in the Middle East and particularly the contradictory promises made at the time of the First World War.

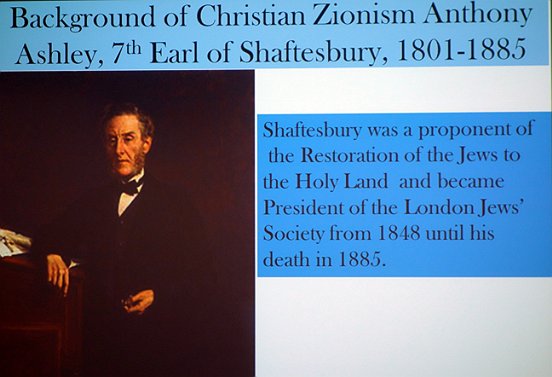

Professor Mary Grey looked at the main players of the Balfour Declaration. She looked at the Christian Zionist background of some Cabinet members – tracing this back to the 19th century inspiration of the Earl of Shaftesbury.  This pre-disposed the government to look favourably at a return of the Jewish people to the Holy Land. Added to this was the key role played by Chaim Weizmann, a Russian –born Jew and a great Zionist leader who impressed Arthur Balfour, the foreign secretary.

This pre-disposed the government to look favourably at a return of the Jewish people to the Holy Land. Added to this was the key role played by Chaim Weizmann, a Russian –born Jew and a great Zionist leader who impressed Arthur Balfour, the foreign secretary.

Our colonial legacy in Palestine is dishonourable not least because Britain made contradictory promises to the Jews and the Palestinians before and after the First World War. Before the Balfour Declaration in 1915, Britain promised Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca, that it would support an independent Arab kingdom under his rule in return for his mounting an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s ally in the war. The promise was contained in a letter dated 24th October 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, to the Sharif of Mecca in what later became known as the McMahon–Hussein correspondence.

A year later in 1916, Sir Mark Sykes and George Picot, the French ambassador, concluded the Sykes–Picot Agreement, dividing up the middle Eastern countries between France and Britain. Not only were these agreements contradictory, but after the Balfour Declaration (1917), the rights and expectations of the Arabs were ignored.

Had the British government meant to honour its promises at all? As Balfour himself said in a memorandum of 1919:

… For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country.’[1]

What really matters now, she concluded, with the words of Naim Ateek, of Sabeel, the liberation theology group of Palestinians in Jerusalem: “What matters about your project is what effect it has on the people on the ground today.”

The next speaker, Rabbi Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok, quoted from a dialogue he is engaged in writing with Mary Grey on the Palestine–Israeli conflict. (Forthcoming) He accepts the Zionist view that it is it is inevitable that Jews, as a minority, will continue to be persecuted just as they have been for centuries. He thinks that at the time – the end of the 19th century – we had an obligation to provide a homeland for the Jews.

He pointed out that apologising for the Balfour Declaration would delegitimise the state of Israel. Was the Balfour Declaration dishonest? Yes, if Palestine was promised to Arabs as part of an Arab kingdom as were Jewish and Christian minorities in Palestine. But he does not agree that Palestine should be part of an Arab kingdom.

Rather, he urged us to understand that Balfour was sympathetic to the plight of the Jews and felt Britain should do all it could for persecuted Jews in Eastern Europe. “If you are against the Balfour Declaration, you are against Israel as a homeland for the Jews,” he said. He thinks the case for the Balfour Declaration is that the persecution of the Jews causes the need for a Jewish state as a solution for anti-Semitism. “If you want an apology for the Balfour Declaration you delegitimise Israel.”

Response: it should be noted that the Balfour Project is not asking for an apology for the Declaration but aims to educate the British people on the decisions taken by our leaders and to acknowledge them. We are ashamed of the deliberate decision of Britain to ignore the second part of the Declaration [to protect the interests of the Arab residents of Palestine]

Dr Dawoud El-Alami, University of St Andrews

Dawoud El-Alami was born in Jerusalem. All his family’s land in the West Bank and Gaza was stolen by Israel in 1948 so he has spent his life whole abroad as an exile.

He quoted Churchill speaking to the Palestine Royal Commission, 1937:

“I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly- wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.”

Referring to the McMahon correspondence, Dawoud asked what right did Sharif Hussein have to speak for the Palestinians. “The Palestinians do not have a voice. Others decide what they should do.”

Rabbi Charles Wallach

Rabbi Charles quoted widely from a biography of Balfour– Arthur James Balfour: the happy life of the politician, Prime Minister, statesman and philosopher. 1848-1930 by Kenneth Young.

Although a member of Rabbis for Human Rights, (in Israel) – he was one of the founders – Rabbi Wallach also feels that there is no need to apologise for the Balfour Declaration and that it would be wrong to do so. He recalled that in 1902 Britain offered a homeland for Jews in Uganda. Balfour first met Weizmann in 1906 and was told that Jews would only accept a homeland in Palestine.

John Bond

John Bond told us about the Stolen Generations, the many Aboriginal people who were forcibly removed from their families as children by past Australian government agencies, and church missions. Aboriginal children were removed from their families with a view to them being employed by colonial settlers, and to stop their parents, families and communities from passing on their culture, language and identity to them.

A report on this hidden chapter of Australia’s history recommended that the government of Australia should say sorry to those who suffered under the forcible removal policies by issuing a formal apology. The report also recommended that there be a national ‘Sorry Day’ held each year.

A short film illustrated how profoundly many aboriginal and white Australians were moved by participation in a very well attended march across Sydney bridge and at meetings arranged under the Sorry Day initiative. It appeared a very valuable way of fostering forgiveness and reconciliation.

Mark Owen chaired the plenary session: some responses included:

- How helpful is history in shaping/informing the future?

Stephen Sizer: “God’s promise of the land to Abraham was conditional on sharing.”

Dan Cohn Sherbok: “It is crucial for both sides to look at things they should not have done”

2.How do we deal with competing/contradictory histories?

Rabbi Wallach: “We need to support Israelis and Palestinians sharing their stories. The Balfour project should encourage this.”

3.Should the British government apologise for the Balfour declaration?

Britain should take responsibility for what was done.

Dan Con Sherbok: “Truthfulness and reconciliation are needed. Get the Israelis and Palestinians to say sorry that they have done wrong. This would be more use than us apologising for Balfour. .”

4.How would an apology help the situation on the ground?

5.Can examples of reconciliation be transferred across conflicts and cultures?

The Irish have forgiven the UK for the famine in the 19th century.

One person felt that it was useless to try to involve extremists in reconciliation.

6.What practical steps can we take to foster peace in the Middle East?

John Bond: “We all have the power to do something.” Approach present generation of Palestinians and Israelis.

It was felt that the day offered positive space and opportunity for honest discussion.

But the Balfour Project aim is to encourage the British to look at their past actions and decisions.

William Dalrymple wrote recently following David Cameron’s visit to Amritsa that he was not in favour of apologies but: “What Cameron can do, however, if he feels real contrition for Britain’s past, is to make the teaching of the British empire a compulsory part of the GCSE history syllabus. The empire was, for better or worse, the most important thing the British ever did: it completely changed the shape of the modern world. Yet most British people are by and large completely unaware of the details of their imperial history. My own children learned Tudors and the Nazis over and again in history class, but never came across a whiff of Indian history.”