Online talk given in January 2022

Wafa Dakwar – Programme Manager, Beirut, Medical Aid for Palestinians

Rohan Talbot – Advocacy and Campaigns Manager, London, Medical Aid for Palestinians

Click here to view MAP’s position paper: Systematic Discrimination and Fragmentation

Click here to download Rohan’s presentation as a PDF

Click here to view the UNRWA Q&A that Rohan mentioned

Rohan Talbot:

I’m sure many of you know about Medical Aid for Palestinians and what we do. The name, I guess makes it fairly obvious, but we are a health and development charity. We work in local partnerships through our offices in the West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, and the UK. Our programmatic focuses that Wafa will speak a little bit more on in a bit, are women and children’s health, mental health, and psychosocial support, disability and emergencies and complex hospital care. And obviously during the COVID-19 pandemic, an emergency response has been a significant part of our work, but we also have an advocacy and campaigns arm, a team of four of which I’m one quarter, that works both in public advocacy and campaigning and private advocacy with MPs and governments and others to try and highlight and draw attention to the political, social and economic barriers to Palestinians’ rights to health and dignity and try and promote policy actions that may address those.

So, I’m going to start by just addressing some of the historical and political context, but after that, I’ll hand over to Wafa, who is far better equipped to speak about some of these issues than I, and I’ll come back at the end to speak a little about the policy responses to some of the issues we raised.

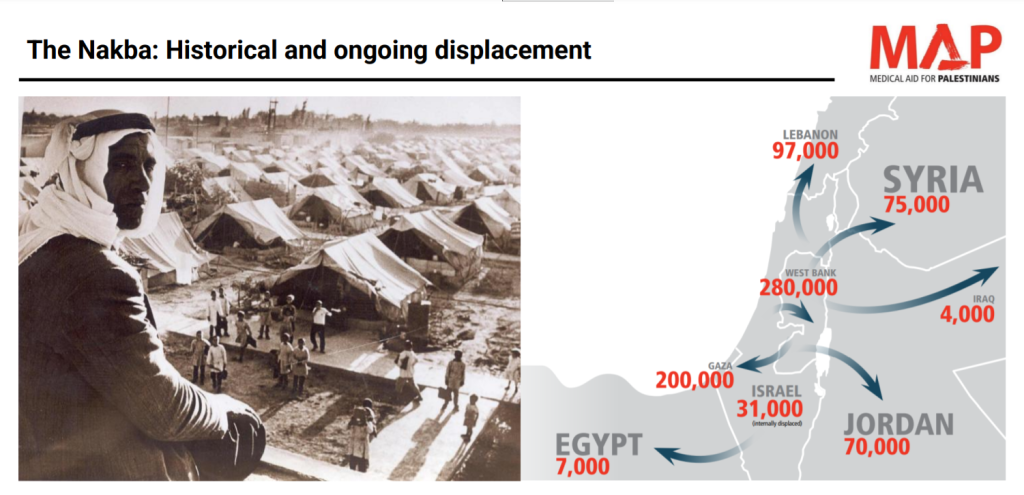

Between 1947 to 1948, at least 750,000 Palestinians were expelled from or fled their homes during the violence and the violent events related to the creation of the state of Israel. This meant the expulsion of more than half of the native Palestinian population, with hundreds of towns and villages completely depopulated, emptied of their inhabitants and destroyed in what Palestinians of course call the Nakba or catastrophe.

These refugees, as you can see from the map we have here, were displaced to Syria, to Jordan, to Gaza, to the West Bank, a small number of around 7,000 to Egypt, and of course, around 97,000 to Lebanon, most of those coming from coastal towns of Haifa, Yafa, as well as Safad, Acre and Nazareth. Other Palestinians fled or were expelled to Lebanon during the 1950s, of course, during the war of 1967 and some from Jordan in 1970 as well.

Today, one in three refugees around the world is a Palestinian. There are just over five million refugees registered with the UN Relief and Works Agency, or UNRWA, which was founded by the UN General Assembly to initially provide temporary humanitarian relief and employment for those refugees who were displaced and has now taken on education, healthcare, social services and protection functions across its five areas of operation. Palestinian refugees are now of course, into the 74 years of displacement and for them, the Nakba is very much an ongoing issue.

Today, there are around 450,000 Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA in Lebanon, living in 12 official camps, as well as additional informal gatherings in other places. The actual numbers of Palestinian refugees in the country are pretty hard to assert with certainty, but recent surveys have reported a population in the camps and gatherings of around 174,000 and UNRWA’s planning numbers for our population of around 210,000. But like I say, the official registered number’s 450,000.

The history of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon is of course marked by repeated tragedy, conflicts, discrimination, and marginalisation. There’s been a host of different marks in history, including the Lebanese civil war, the massacres in Tel al-Zaatar 1976 and Sabra and Shatila in 1982, the war of the camps and the siege of [inaudible 00:04:30] in 1984, the [inaudible 00:04:34] conflict of 2007 and of course, since 2011, there’s also been an influx of double displaced refugees from areas such as Yarmouk, Daraa and Ayn al Talv from the civil war in Syria.

MAP’s story of course is also connected to these tragedies. Medical Aid for Palestinians was founded by humanitarian volunteers who had been in some of them and witnessed the devastation, the massacre in Sabra and Shatila in 1982, including Dr. Swee Chai Ang, who you can see pictured, just in the small picture in the middle, who was working in the Gaza hospital in the camp at the time of the massacre.

At this massacre, during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, Israel’s army encircled the refugee camp at Sabra and Shatila and supported an allied Christian militia called the Lebanese Forces to enter, where they killed and injured hundreds of unarmed Palestinians and other civilians inside. By that point, of course, Palestinians had already been in Lebanon for more than 30 years as exiles and refugees, and we’re more than double beyond that now.

Today, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are classified as foreigners under Lebanese law, and they continue to face very severe institutionalised discrimination and exclusion from many key aspects of social, political and economic life in the country. This includes being excluded from accessing many public services, from owning or inheriting property, and a host of legal, bureaucratic, and social barriers to their right to health. In particular, barring them from working in 39 key professions, such as law, engineering and most healthcare jobs, as you can see on the screen, being a doctor, a nurse, a midwife and nutritionist, a dentist, a vet, et cetera.

This situation obviously resigns most Palestine refugees to very insecure and poorly paid labour, high rates of poverty and unemployment, with really severe implications for their humanitarian welfare and the right to health of refugees, which is what Wafa is going to speak about now.

Wafa Dakwar:

Hi everyone. I’m Wafa Dakwar, Programme Manager of MAP in Lebanon. I’m also a Palestinian refugee. So, I’m going to talk about the context of the Palestinian camps, the current crisis and MAP’s response. Despite being in Lebanon for more than 70 years, more than half of Palestinian refugees continue to live in 12 refugee camps across Lebanon. These camps have dire conditions.

They’re overcrowded, for example, in Ain al-Hilweh Camp, whose area is around 1.5 square kilometers, hosts around 80,000 refugees. The housing conditions are substandard, poor ventilation, very narrow space between the houses, natural light does not access most of the houses and the buildings are old and at risk of collapse at any time. The camps also have inadequate infrastructure, poor water quality, electricity provision, and waste management. Water pipes mix with hanging electricity wires, and are at the reach of people and children. Every year, tons of people die because of electrocution with these wires.

There are no safe spaces for children to play in the camps.

The camps’ residents and the Palestinian refugees in general in Lebanon suffer high levels of poverty. 65% of Palestinian refugees were living in poverty in Lebanon, even before Lebanon’s severe economic crisis, compared to 28% of the Lebanese population.

Palestinians have been embedded in improving the living conditions by financial constraints and restrictions imposed by the Lebanese government. These conditions have a negative impact on the health and wellbeing of Palestinian refugees. There is a strong correlation between the high level of poverty and ill health in the Palestinian community. Prevalence of functional disability among Palestinian refugees is estimated to be twice as high as that for the Lebanese population. Also, communicable diseases are also common among refugees, due to the poor housing conditions, overcrowding and lack of proper sanitation and infrastructure of the camps. This has been a major issue with COVID-19, where physical distancing and isolation are almost impossible in this context.

The impact of these living conditions and circumstances on mental health of adults and children is considerable. A study by the American University of Beirut in 2015, found out that over half of the surveyed Palestinians reported poor mental health.

The healthcare system that is available for Palestinian refugees is inadequate and fragmented. The Lebanese government does not provide Palestinian refugees healthcare services. The key actors, or the key stakeholders for Palestinian refugees include UNRWA, Palestine Red Crescent Society, NGOs, local and international, and the private sector.

For primary healthcare, Palestinian refugees go to UNRWA’s primary healthcare centres. The key issues include, include the fact that these services are overstretched and that UNRWA is chronically underfunded. For secondary care UNRWA covers the cost of hospitalisation at Palestine Red Crescent Society hospitals fully, or at Lebanese hospitals, at around 90% of the cost. The issue is that there is limited capacity and again, underfunding. For tertiary care, Palestinian refugees receive these services at Lebanese health facilities and UNRWA covers 60% of the cost. The issue here is that cost sharing is a barrier to accessing these services for Palestinian refugees.

NGOs usually fill the gap in the existing health system. For example, they focus on health promotion, prevention, mental health and psychosocial support, disability, specialised services, all these are gaps in the system. So NGOs fill this gap. The issue with NGOs, that most programmes are donor funded, so they have a problem with sustainability.

Since 2019, Lebanon has been experiencing a severe economic crisis, which is considered among the top three worst crises in the world since the mid-19th century. The currency devaluated by more than 90%, purchasing power of households collapsed, especially those that are paid in Lebanese pounds. Inflation reached an all-time high, the economy contracted and thousands of businesses closed. Unemployment rates soared in the last two years, and many are leaving the country, looking for job opportunities abroad, especially healthcare workers and youth, which is leading to a brain drain.

COVID-19 restrictions caused further socioeconomic deterioration and loss of livelihoods. Palestinian refugees were greatly affected by COVID-19 lockdowns as they mostly work in the informal sector and they rely on daily pay. In 2021, 74% of the population in Lebanon were living below the poverty line, compared to 55% in 2020, and 25% and 2019. The impact of this crisis was proportional to wealth, was marginalised groups, including Palestinian refugees hit hardest. Unemployment, poverty, and food insecurity have significantly increased among Palestinian refugees following the crisis. The most vulnerable communities, including Palestinian refugees are left at risk of further marginalisation and deprivation in the absence of an effective protection scheme.

Following the crisis, food prices at least quadrupled and for some essential items increased for by 700%. This led to an increase in food insecurities. Families started resorting to negative and risky coping strategies to secure essentials, such as selling productive assets, forgoing medical treatment, reducing the number of meals, substituting proteins for carbohydrate. These food-based coping strategies could lead to longer term malnutrition, especially for pregnant women and children under five. There is also an increased risk of exploitation and risky behaviors.

The overlapping crisis in Lebanon affected the provision of basic services. For example, we have less than two hours of government electricity per day. There is severe fuel shortages. The government lifted fuel subsidies, which led to an increase for example, of more than 2000% in a tank of diesel oil, which is used for heating and for alternative electricity supply, which means that Palestinian refugees could not be able to secure heating during the cold winters. Also, the increase in fuel prices led to an increase in transportation costs by like 500%, causing additional restrictions to mobility and access to essential services.

There is constant worry that Lebanon’s water system is at the verge of collapse. 71% of Lebanon’s population are at immediate risk of losing access to safe drinking water. These shortages are affecting every vital sector in the country, including the health sectors health sector and hospitals.

The crisis had also a negative impact on children. The families are taking their children out of school, they’re sending them to work. Children reported skipping meals, cutting expenses on education. So they were highly affected by the crisis.

During the last two years, MAP continued to deliver its regular programme, which works to improve the health of Palestinian refugees, promote the divide access to healthcare, bridge gaps in health services, to Palestinian refugees, and strengthen the capacity of the main constituents, local providers of the health system for Palestinian refugees. Lebanon’s programme focuses on women and child health, mental health and psychosocial support, disability, emergency response, and complex hospital care.

We also extended existing services, for example, increased the number of community midwives to be able to assist more vulnerable mothers and newborns, introduced malnutrition screening for children under five during home visits by the community midwives, also established hotlines to provide the emergency support, like psychosocial support or support to victims of gender-based violence during lockdowns. We also started the new emergency response projects such as in providing winterisation assistance for vulnerable families living at high altitudes. And also, we supported Palestine Red Crescent Society hospitals by providing them with medical supplies, personal protective equipment, essential equipment that they needed to make sure they’re able to provide hospital care for the most vulnerable.

Also, we provided food parcels for nutritionally vulnerable groups, for example, pregnant women, lactating mothers, elderly, and our poorest families. Also, we are starting a new capacity development project that works with all Palestine Red Crescent Society, UNRWA and disability organisations in the area of neonatal care and early childhood development.

So far we had good successes, but with deteriorating situation and conditions in the country more will be needed in order to keep on meeting the needs of Palestinian refugees. Thank you.

Rohan:

Thank you so much, Wafa, it’s really sobering. As I mentioned before, we’re talking about an incredibly chronic and protracted humanitarian crisis, but one that seems to just be nose-diving at the moment in Lebanon, in particular, because of the economic circumstances there.

I’m just going to bring our part of the presentations to a close by talking a little bit about policy responses and what the UK and other governments can be doing to try and address this situation. Because difficult though it is, especially in the macro level of the economy and politics in Lebanon, there are very specific actions that can and should be taken in the short, medium and long term to address some of these issues.

One key issue right now as mentioned by Wafa is UNRWA and UNRWA’s financial crisis. The Agency is obviously an essential humanitarian safety net, one with the near-unanimous buy-in of the international community, but it is suffering what the Commissioner General Philippe Lazzarini has described as an existential funding gap. This is a chronic issue, of course, because funding for the agency has been stagnant since around 2013, despite the fact that needs have been increasing since that period of time, in part because of the deteriorating situation in Gaza, the war in Syria and of course now, the very desperate situation in Lebanon.

Towards the end of last year, UNRWA had a shortfall of approximately $100 million just to keep services running, with uncertainty over its ability to pay the salaries of its approximately 28,000 staff. Austerity measures mean that it’s currently running class sizes in its schools of around 50, its health services are giving consultations of less than three minutes to people coming in for primary care consultations and, despite obviously the UK’s stated support for the organisation and its very important historic responsibility for the refugee crisis and towards Palestinian refugees, the UK has cut its annual contributions to UNRWA from around $70 million dollars a year in 2018 to around $28 million last year in the context of the UK’s broader aid cuts.

The Agency is also not only suffering a financial crisis, but also a potential political one as well, as it has come under very sustained political attack from the state of Israel, as well as anti-Palestinian activists, and of course, the cuts from the former Trump administration, all of whom have accused it of ‘ perpetuating a refugee crisis’ when in actual fact, it is there only to maintain some modicum of dignity and humanitarian support in a refugee crisis that’s caused by other factors.

So immediately, there needs to be an injection of funding to UNRWA, to not only enable it to meet immediate needs, but also to find endurable multi-year funding to enable it to provide proper planning for its services and ensure that it can end this very serious austerity drive that it’s been forced to take. But it’s also important that the UK and others are vocal and vociferous in their support for UNRWA on the international stage and bolster its legitimacy and political support.

But we also need to look beyond UNRWA and a lot of the time when we talk about Palestinian refugees from a policy perspective, I think it gets stuck in the conversation about UNRWA but there are a host of other actors, really important ones, many of them Wafa just mentioned, including the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, local civil society groups that also needs support from countries like the UK.

The UK should also be supporting professional development initiatives for Palestinians, particularly young people, including through, for example, the expansion of international scholarship opportunities for health and other workers to be able to train overseas, including for example, in our NHS. We also need a radical shift and overhaul in the process of foreign aid policy development with regards to Palestinians and Palestinian refugees, which puts Palestinian communities, their voices and their priorities of their heart, true partnership and true consultation in determining what the priorities for the UK and others’ aid policies will be.

Now, those measures that I’ve outlined are achievable, of course, and they’re important to the immediate term at a time of very severe crisis, but ultimately there aren’t humanitarian solutions to what are at their heart political problems. So, in the immediate term, of course it’s important that the government of the UK is pressing Lebanon on to remove many of those discriminatory laws and policies and practices against Palestinians that I mentioned before, who remain in exile in the country.

Palestinian refugees are among the best educated populations in the Middle East and indeed in the world, including in Lebanon, but they face a very severe lack of opportunities and unlocking that, enabling Palestinians to work legally in Lebanon, without restrictions, will not only support them and the economic life of their families and the camps of course, but also fill very important and severe skills gaps in the Lebanese economy, for example, in nursing and other professions.

But ultimately, we need to recognise that the reason for this perpetual humanitarian crisis, a 74-year humanitarian crisis, arguably the longest perpetual crisis in the world, the reason that we are speaking today is 74 years of the denial of Palestine refugees’ rights, including their rights to return to their homes and remedy and compensation for the property that was taken from them during the Nakba. The right to leave and return to one’s country is a right that we all hold dear. It is reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is codified in article 12 of the International Covenant in Civil Political Rights and article five of the International Covenant on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. For Palestinian refugees in particular, it was upheld in UN General Assembly Resolution 194 and has been reaffirmed consistently by the international community since then by UN resolutions and of course by UN treaty bodies.

But this right continues to be denied and it is denied by a discriminatory legal framework imposed by Israel, including its 1950 Law of Return, and its 1952 citizenship law, which permit immigration and citizenship to the state of Israel, exclusively for Jewish people from around the world, whilst denying these to Palestinians and Palestinian refugees who fled and were forced out of their homes, and lands, and territories during the Nakba. This issue is not going away. Much as those who would seek to deny Palestinians these rights might wish it, undermining or destroying UNRWA, or attacking Palestinians’ legitimate rights at the UN or other places, will not eliminate Palestinian refugees nor their legal status, nor their rights.

So in order to address many of the problems that we’ve just spoken about, we need to look at the core issues and governments like the UK must make upholding Palestinian rights, including return and including remedy, a priority. This ultimately means accountability. This means tackling the systematic discrimination and fragmentation of Palestinian people imposed by Israel, that imposes a life of permanent limbo on refugees. It imposes a permanent humanitarian crisis and it perpetuates a dependency of course, that requires international support, including from the UK.

If people who are watching are interested in this issue, we recently released at the end of last year, a position paper, which explains how systematic discrimination and fragmentation constitute fundamental barriers to Palestinians’ rights to health and dignity, not only in the OPT where we tend to think about discrimination and fragmentation, particularly in the West Bank, for example, but actually in Lebanon too, how those policies and practices are fundamental barriers to the long-term realisation of Palestinian refugees’ rights. It makes an number of recommendations of course, for policy makers, on how some of these issues can be addressed. So, that’s it from us and I’m sure we’re both very eager to hear your questions.

Diana Safieh:

Hello, so thank you so much for that, that was … Well, it was depressing in all honesty, but very fascinating and thank you. I know it’s a subject that a lot of us are really keen to understand more about.

So, I will get started with questions so we can get through as many as possible. From Magan Singodia, who is on the executive committee and board of the Balfour Project, his question is, “What rights do the Palestinian refugees have in Lebanon versus Lebanese citizens themselves?”

Wafa:

Okay, so Palestinian refugees in Lebanon do not benefit from the state’s public services. For example, they do not benefit from public healthcare or free healthcare that the Lebanese government provides to the Lebanese citizens. Palestinian refugees cannot work in many professions. For example, a Lebanese can’t be adopted by a Palestinian refugee, would not be able to practice a profession such as medicine, law, and many others. Also, for example, in education, Lebanese are able to get free education supported by the Lebanese government, not the case for Palestinian refugees. Rohan, would you like add?

Rohan:

Just maybe to add a little bit of colour to how difficult and how arcane some of these issues are. I mean, everything that Wafa’s just said, but to zoom in on the right to work, we have a paper, a report from 2018 called Health In Exile, that digs in specifically to the right to work, which is obviously fundamental to the realisation of the right to health and other rights as well. The barriers are sometimes law, sometimes practice, sometimes policy, and it can be very difficult to navigate it. So, for example, on barriers to the right to work, there was a 1964 ministerial decree, which imposes three conditions on foreigners being able to work in Lebanon. One of them being reciprocity, so the country that that ‘foreigner’ comes from, their country of origin needs to provide the same equivalent right, to Lebanese people in that area.

The requirement of national preference, so that imposes the idea that if there are two people competing for a job, then the Lebanese person should have preference, and of course, obtaining a work permit. Obtaining a work permit is a real bureaucratic nightmare for Palestinians. It needs to be renewed, and correct me if I’m wrong on any of this Wafa, because I know that it changes quite regularly by ministerial decree and other things, but certainly a couple of years ago, it needed to be renewed annually. If you’re earning more than twice, I think the minimum wage, then it needed to be approved by the director general of the Ministry of Labour. Ultimately, I think less than 2% of Palestinian workers in Lebanon actually have them because it’s almost impossible. Employers don’t want to go through all of that rigmarole to try and apply for a permit.

Even if you meet all the requirements, and you get a work permit and you are working legally in the Lebanese economy, you’re still excluded from some of the rights that should come with that. So, you will get certain rights, such as end of service provision, work-related indemnity, but you won’t get the health and the maternity benefits of social security. So, even if you’ve gone through all of those bureaucratic processes, even if you are able to get yourself a work permit that’s renewed annually and you get a job, you’re still not able to receive the full gamut of rights that Lebanese people would be in the same circumstances.

Diana:

Well, we’ve got a follow-up question from Martin Linton about the right to vote.

Wafa:

No, you’re not allowed to vote. Even if you’re born in the country, you’re still not allowed to participate in political life, to vote. Also, you’re not allowed to own property, like immovable property, or to travel freely. There are many things that Palestinian refugees don’t have equal to the Lebanese citizens.

Diana:

Thanks for that. The next question “Is there a clear distinction between the state and the people in regard to treatment of the Palestinian refugees?” What’s the attitude of the general population to the refugees?

Wafa:

Yes. The state has discriminatory policies in terms of laws, they’re discriminatory. Whereas people, they have been living together for more than 70 years, so in many ways they don’t have this hostility among one another.

Diana:

Thank you. You’ve touched on this, but just to clarify, we’ve got a question from Joe Cairns. “Who is responsible for administration and government of the camps? Why is unsafe electrical wiring allowed to drape across passageways?” Which I believe was in Wafa’s presentation.

Rohan:

I would say that, well, it’s not Lebanese municipality. So, they’re excluded entirely from of the oversight and control from Lebanese municipalities. There’s no services, for example, provided by Lebanese government. So, things like rubbish collection for example, are provided by UNRWA. So, it becomes entirely informal. When we talk about refugee camps, I guess certainly in the UK, we tend to conjure up a temporary circumstance of people with tents, but of course after 74 years, people can’t live in tents with an expanding population. So what you end up having is, from those initial buildings that were set up as a semipermanent building, people then build a floor on top for their children and then a floor on top for their grandchildren, etc.

And within that, there’s no planning, there’s no official infrastructure to provide for people. So, it becomes entirely informal and it’s really dangerous. I mean, one of the things that we don’t necessarily talk about, and I hope that we never have to encounter, of course, that there’s geological faults close by and the incidence of things such as earthquakes and with informal building, unregulated building, some of it quite tall now, like I said, after 74 years and overhanging wires, poor water infrastructure, very tightly, closely packed together buildings, so people on lower floors get no sunlight and very poor ventilation, which has obviously been an incredibly difficult and important aspect to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the reason that COVID spread very quickly through the camps in the early stages. There really is no regulation.

Now again, we have to zoom out a little bit and say that no one should be forced to live in perpetual exile and have to build these informal spaces. Lebanon has hosted a very significant Palestinian refugee population for a long period of time. But at the same time, while recognising Palestinians’ fundamental refugees rights as I mentioned before, it doesn’t necessarily have to be that they are forced to live in these really dire and unacceptable conditions.

Diana:

Here’s an interesting one from Peter Brain. “What was the impact of the Beirut explosion from a year and a half ago on the Palestinian refugees?”

Wafa:

Yes, yes. The country was already suffering the economic crisis and the Beirut blast came and made the situation much worse. It diverted many valuable resources that usually go to essential services to rebuilding, to recovery. It put the strain on the health system, on all the systems in the country.

Rohan:

I just wanted to say one of the reflections that I thought was remarkable at the time. Like you say Wafa, the country incredibly strained in its ability to cope, really difficult before that even happened. But I thought it was really remarkable that the Palestinian Red Crescent Society hospitals were sending their medics out to support people and treating everyone that came across theirs. I think that it says something important about that openness and that willingness to step out and support, even in those difficult circumstances and the severe resource constraints that the RCS face.

Wafa:

Despite their limited resources, they opened their hospitals and their paramedic and they were helping everyone, regardless of their nationality, Lebanese, Palestinians, everybody.

Diana:

We have a couple of questions on this theme about education of the Palestinian refugees in the camps. But for example, Mary Collett has asked, “How is it possible for Palestinian refugees to become so highly educated?”

Wafa:

They believe that education is the right thing to do. Education is the way forward. Palestinian refugees like to educate their children. Palestinian refugees, mainly receive educational services from UNRWA schools and those who are able to pay receive it from private schools. But yes, education is very important for Palestinian refugees. It is the most, many times the families do not spend on food or on many things, but they prioritise spending on education because it is the way to have a better life. They believe that it is the way to have a better life.

Rohan:

It’s also, if I can, one of the great successes I think of UNRWA and the work that that they’ve done. I don’t know what the latest figures are, but the last time I saw it, the literacy rate of Palestinian refugees was somewhere around 97%, which is high anywhere in the world. I mean, it’s a remarkably high rates that also, it’s not just about education, but also dignity and upholding that basic right and dignity is so important. What the challenge is of course, is translating that into opportunity.

From my own visits and times in Lebanon, it’s very clear that at young people are incredibly smart, incredibly well-educated, incredibly keen to use those talents in ways that support themselves and their communities. I think that that high level prizing of education is also expressing itself in interesting ways, as Palestinians start to come next beyond Lebanon, into other places on the basis of that common identity. It’s quite hopeful, even in those difficult circumstances of not having a lot of opportunities locally.

Diana:

I remember that reading a fact that in 1967, 10% of all Arab university students were a Palestinian. Obviously, that’s disproportionate compared to the relative population size. So, going forward on the topic of university education, Marjorie Hancock has asked whether Palestinian refugees in Lebanon can attend Lebanese universities?

Wafa:

Yes, if they pay they attend, yes.

Diana:

We’ve got a question from Sir Harold Walker, Hooky to his friends. “We were told MAP works with local partners. Who are the main partners, are there too many to name?”

Wafa:

Yes. We work with the local organisations and we work with them to provide the services, but also to build their capacity. We do work with UNRWA, Palestine Red Crescent Society hospitals, and local NGOs, local civil society organisations. I can name a few, for example. General Union for Palestinian Women, Palestinian Women Organisation. They’re doing a good job for their fellow refugees.

Diana:

We’ve another question about the curriculum. Is there any interference from the Lebanese government on the curriculum at UNRWA schools in the camp? That question by the way, was from Ian Chalmers.

Wafa:

The same curriculum is used by UNRWA schools and the Lebanese schools, because everyone sits for the official exams. We have the same official exams for Palestinians and refugees, so the curriculum has to be the same for everybody.

Rohan:

This is in line with international best standards for refugees, of course, that need to be able to access opportunities while in exile, and therefore obviously, be able to connect to their local context and have access to the opportunities from those qualifications that they get within the education system.

Diana:

I’ve got a question from Tim Llewellyn who’s on our executive committee of the Balfour Project. He would like to know, “How easy or difficult is it for Palestinian refugees to travel in and out of Lebanon?”

Wafa:

No, not easy, not easy. You need to a visa, you need to have a proof that you’ll be coming back, which is that you’re working, invitation. No, it’s very complicated.

Diana:

I predict that Tim knew that it was complicated and would like that to be highlighted. I’ve got a question from Ronald Mendell to the two presenters. “The situation described by both speakers is dire and perhaps self-perpetuating, despite the work of UNRWA and Medical Aid for Palestinians. However, can it be argued that an unintended consequence of this intervention is to normalise the situation for refugees? Are we perpetuating the situation?”

Rohan:

Maybe I’ll step in because I address that a little bit in the talk. UNRWA is vitally important, it provides an underlying baseline of dignity, a baseline of humanitarian needs. It doesn’t create future opportunities. It also lacks the mandate, for example, the UNHCR has, for seeking resolution, including return for refugees. The perpetuation of the situation is political, it’s not to do with having a humanitarian support. You could pull that entire rug away and all that would happen is that Palestinians would have a more severe humanitarian crisis and have less opportunities and less dignity. Given what Wafa was talking about in Lebanon, at the moment, you would create famine, healthcare emergencies, these sorts of things that would be entirely manmade.

Palestinians, like all refugees, including multi-generation refugees, have the right to return to their homes and have the right to compensation for what has been taken from them. This is exactly the same, for example, in multiple generations of refugees from Afghanistan who are living in Pakistan, for multiple of refugees from Somalia. Of course, we’re looking at it in Syria, refugees from Syria today. People who left Syria, it’s not safe or they’re not able to return, and they have children. You have these multiple generations where there’s a continued family and national link to the place that they came from. That right is inalienable, it’s a right that I would claim as a British person if I was forced to leave my home or left and couldn’t come home, I wouldn’t stop being British. I wouldn’t stop claiming the right to return. I wouldn’t stop claiming the right to the house that I’m in now, it’s my property and we shouldn’t perpetuate this conversation, this idea that for some reason, Palestinians are the exception to that rule, that basic fundamental human right, that basic fundamental source of dignity, of being able to return to your home just because it happened a long time ago.

The average length of displacement for a refugee in any context at the moment around the world is 20 years. That’s enough time to go from child to adult, to potentially parent as well in that period of time. Those people and their children maintain their rights as refugees and Palestinians do exactly the same. So, removing a humanitarian rug from underneath Palestinian refugees, all that does is create suffering. The way to resolve it is to address those core issues.

Diana:

I’ve got question from Joshua Rowe, which touches on what you said about how the average refugee timeframe is about 20 years. “Why does UNRWA exist? Why do we have fifth generation refugees when all the tens of millions of refugees all around the world post-1948 were given support for one generation only and are now fully integrated into their host nations?” So, what makes the Palestinian situation so different?

Rohan:

That’s not true and I mean, it’s exactly the same circumstance for Palestinian refugees and other places. Like I just said, there are people, for example, still living in Pakistan who were displaced during the ’80s. And there are people displaced from Sudan and Somalia as well, multiple generations from the Congo as well. Under the UNHCR mandate, there are three options for a refugee under international refugee law, one of which is integration into the host country if the refugee chooses it. The second is to be resettled to a third country, if it can be arranged, and if the refugee chooses it. The third of course, is return, safe return to their homes and all refugees maintain that right should they choose it.

This is both a legal right that exists both for Palestinian refugees and every other refugee around the world, and it’s also, just put it in your own context. If you were forced from your home and your children were growing up in your exile, you would expect to be able to return to your home and property, just as others would. That’s a right, it’s the law, it’s the same. The exception is applied to Palestinians by arguing that they aren’t granted that right. Palestinian refugees are not given any exceptional right for multi-generation families.

I’ll maybe send a link round because UNRWA has a really good, short, pithy Q and A on this. It’s really important. And this is what I was saying earlier in my presentation about the political attacks, not just on UNRWA but also on Palestinian refugees’ rights more broadly, that there is a narrative being spun with a particular agenda behind it, to deny the very dignity, the national and personhood of Palestinian refugees. We need to be really careful that we’re not being clouded by what is fundamentally just not a true reading of international law. Don’t have to take my word from it, you can read the UN resolutions, which maintain this right for Palestinian refugees and have done since 194.

Diana:

We’ve got a question from John Munro who wonders, “What are the percentages of men, women, and children within the camps?” Do we have any numbers for that?

Rohan:

I think it’s fair to say a very high population of children in.

Diana:

Speaking of within the camp, I’ve got a question from Sue Cook, “Do any Israeli human rights organisations have a presence in the Lebanese refugee camps?”

Rohan:

I think it’s fair to say no, they don’t, especially in Lebanon. Israel’s state presence in Lebanon, I think we could say, a minor way of putting it, would be contentious and yeah, there’s no presence at all for Israeli civil society. There are Israeli organisations inside Israel doing important work actually, on recognising the history of the Nakba, I’m sure lots of people have heard of Zochrot, which is an organisation that maps those towns and villages that were depopulated and raises awareness within Israeli society and internationally about the Nakba and works very closely with Palestinian activists and organisations like Hadeel and others, to keep that history alive and to keep people aware of it. I think that’s an important internal aspect that happens within Israel itself.

Diana:

We’ve got a question from Bruce Clark who asks, “Who actually owns the properties in the 12 camps or the land that the camps are on?”

Wafa:

I think they are for the Lebanese government.

Rohan:

This is a really good question actually, I’m going to go away and look at this afterwards, but of course as I understand it, the land was basically given as a long-term lease, or as a long-term agreement, I presume. Maybe there’s someone here from UNRWA who can answer the question, but of course, that land has not expanded. It’s an important issue of land. That land that was grant to the 12 refugee camps, has not expanded. The population of Palestinian refugees, of course, as it does, has expanded. There was a statistic, I’m not sure if it’s still true, but Ain al-Hilweh was at one point one of the most densely populated square miles in anywhere in the world. I mean, I’m not sure what their density is, but it’s incredibly densely populated. Large families in small homes, stacked one on top of each other, because the land allotted, despite this increase in population size, has not expanded at all. And that again, adds to the pressures.

Diana:

Thanks for that answer. We’ve got a question from Adrian Liebovitz. “Is MAP’s humanitarian work going to be impacted and made more difficult in Gaza following the UK’s government proscription of Hamas?”

Rohan:

We’re a carefully compliant organisation with all sort of various relevant laws. We’re very carefully audited. Gaza of course is a situation where it’s very difficult to do humanitarian work, because you have to be very, very aware and cautious and have all the due diligence with your partners and the work you do. So, I anticipate that our work, because it is so strictly to the letter and the spirit of law and regulation, will continue.

Diana:

Let’s hope so, because the work you do is so crucial. I’ve got a question from Baroness Jenny Tonge. She would like to know what is happening about COVID vaccinations in Lebanon generally, and within the Palestinian refugee communities in particular? Because of course, they’re dealing with a pandemic on top of everything.

Wafa:

Palestinian refugees, as well as Lebanese citizens have access to the equal access to vaccination. So, based on specific set of the criteria, you can get your vaccine regardless of your nationality. It’s ongoing, it’s ongoing now, the vaccination.

Diana:

Okay. Well, there must be some understanding that it only really works if you get the majority of people vaccinated. We’ve got a really interesting question from Liam Allmark, which hopefully you can give us some insight, probably Wafa? “Is the position/status/welfare of Palestinian refugees likely to feature much in the campaigns around Lebanon’s elections this year?” Is that something that comes up in lobbying?

Wafa:

Yes, usually it comes up. They use them to get more votes if they’re against Palestinians or more votes if they are pro-Palestinian. So, they will be used in this way, they always do when there are campaigns, when there are elections. But I don’t believe that the aim or the purpose of this is to improve the conditions of Palestinian refugees.

Diana:

I am going to give you the final question. These have come from Sir Vincent Fean, who’s the chair of the Balfour Project and he asks a question that many of our audience have asked in their own way. “How can we in Britain help to relieve the suffering of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon? Is it through pressing our government to support UNRWA, or through supporting MAP, or pressing the Lebanese authorities to allow Palestinians to work?” What’s the best way to focus our energies? Is it all of those, all of the above?

Rohan:

Maybe I’ll start. I mean, yes, of course it’s all of the above, and thank you Sir Vincent, for the question. I would say, and Wafa has outlined that, the first thing for us to say is that MAP is a rare organisation with a very specific mandate towards Palestinian refugees. But also as you’ve mentioned, fantastic local partners. I’m biased because I used to work for one of them, but really brilliant local partners doing important work, integrated into their communities, in a much more horizontal and partnership approach than lots of organisations are able to do. That long history that we have in Lebanon, though we wish we didn’t have to do this work, is impactful. Just to crow a little bit about some of the work, that for example, our team of community midwives are doing. I think they’re remarkable and I hope that some people here will have met them, or will get opportunity to meet them.

There are big gaps for at risk mothers in Lebanon and especially in the circumstance like today, where chronic malnutrition and anemia and those sorts of things are real concerns. Those midwives are every day in the camps, meeting with women, reassuring them, giving them health advice, and the data itself shows that that has an impact and increase in for example, breastfeeding rates and those sorts of things. So obviously, there’s a case for supporting MAP, the work that we do, it’s unique, vital, and so long as these political issues are on the agenda, then we always aim to be there, in genuine partnership and genuine solidarity. That’s the legacy of the beginning of the organisation in the 1980s to today.

Support for UNRWA is essential. I know that in the UK, there is a broader conversation about cuts to international aid, and Palestine and the Palestinians are just one aspect of that. But it’s not only the cuts, but it’s also where those cuts fall and they have fallen very heavily on very dire humanitarian situations in the Middle East, including Lebanon. There’s 66% cut to aid to the Palestinians, even though it’s not a 66% cut to aid overall. Yemen and other contexts as well are important to recognise. So, there has to be more of a public conversation about pushing for that aid to return but especially right now, UNWRA. UNRWA, as Philippe Lazzarini has pointed out, is trying to keep the lights on, it’s an existential crisis and we can’t afford to let those lights go out, the work is vital.

But just in terms of the broader scene, pressing our political representatives in the UK and internationally, MPs and the government, to not only increase aid, but talk about refugees and recognise their rights, find opportunities in the international sphere, the UN and other places, to make sure that Palestinian refugees and their dignity and their rights are upheld and pushing for, an end those discriminatory policies and practices. We sometimes talk, because it’s been such a long time, as if this is an inevitable situation, but it’s not, it’s man-made and it can be resolved by concerted political pressure on action as well. It’s only when, as I said before, those fundamental rights are recognised and addressed and realised, that Palestinian refugees in Lebanon will be able to live in full dignity and the full rights that the rest of us enjoy.

Diana:

Thanks for that, Rohan. Both of you have been so fantastic. You’ve laid out a very complicated issue so clearly for us and you’ll see when I share the chat with you, loads of appreciative comments in the chat box. I just want to share one word from Dr. Swee Ang, who many of us know very well and who is also survivor of the Sabra-Shatila massacre. “Thank you for highlighting the forgotten Palestinian refugees of Lebanon who have suffered multiple displacements, attacks, massacres and deprivations of the most basic human rights.” And that is what it comes down to, isn’t it? It’s this idea and this dream of equal rights for all. So, I just want to thank you so much both of you, for joining us today and thank you all of the attendees for joining us as well and for following us and I have posted the links.