by Peter Shambrook

Oneworld Academic

£35.00, $US45.00

ISBN 978-0-86154-632-9

Review by John McHugo

Before Peter Shambrook produced Policy of Deceit, many historians in the West had shied away from the controversy over the Hussein-MacMahon correspondence of 1915-16. Whatever British commitments the letters contained were deemed ambiguous or obscured by partisan scholarship. Although this view was not universally shared, there was a widespread perception that there was no realistic chance of getting to the bottom of what the commitments meant, or establishing whether they were legally binding.

Yet Arabs have always maintained that the correspondence included an implicit but legally binding British commitment to Palestinian independence at the end of the First World War. What it contained is therefore important. If the Arab interpretation is right, Britain was acting in bad faith when it issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917. The question of which interpretation is correct has divided opinion ever since, very often on partisan lines, and has smouldered on to this day.

The story of the correspondence and the battles over its interpretation has now been comprehensively reconsidered by Dr Shambrook. The quality of his writing is superb. He turns what could have been a rather dry investigation into a gripping story that is easy to read. His research into British archives is truly prodigious. I doubt if any of his predecessors has come close to him in their grasp of the material (some of which may not have been available to them). His coverage of the discussion of Palestine in both chambers of the Westminster Parliament across the period covered by the book is particularly illuminating. He also puts the tale of the correspondence in the context of British imperial policy in Palestine and the wider Middle East, both before and after the coming to power of the Nazi regime in Germany in 1933, in a way that will enlighten all readers.

Dr Shambrook’s forensic approach has given him what will almost certainly be the final word on this topic, although he is far too modest to say this himself. He also points out that there are still some little mysteries thrown up by the archive material which have not been resolved, and may never be (unless there are retained British documents that have not yet been made public).

To this reviewer’s mind, Dr Shambrook shows beyond any reasonable doubt that the British interpretation was not only untenable but deceitful, and that the Arab interpretation was correct, although HMG could never bring itself to admit this. Dr Shambrook also draws attention to many other instances of British dishonesty in its treatment of Palestine, as well as to the parallel dishonesty on the part of Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader. Policy of Deceit is an apt title for the book.

Balfour, 1917, and Britain breaks its promises

It all began on 14 July 1915. The Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, who was the guardian of the Muslim Holy Places in Mecca and Medina and a 37th generation descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, wrote a letter to Sir Henry MacMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt. This initiated a correspondence which led to the Sharif raising the standard of Arab nationalist revolt against the Turks. The Sharif remained adamant for the rest of his life that in the correspondence Britain recognised Palestine as an Arab country entitled to independence at the end of the First World War, and this commitment was part of the understanding that persuaded him to join Britain and the other Allied Powers against Turkey and Germany.

Yet this did not stop Britain issuing the Balfour Declaration well over a year after the Sharif began his revolt. It committed Britain to facilitate the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. Ever afterwards, Britain would be forced to deny that the correspondence made a prior commitment that recognised Palestine as an Arab country and promised it independence.

The Sharif Hussein’s letters to MacMahon were in Arabic, written in long-hand and couched in the style used by hereditary rulers in the Arabian peninsula at that time. The letters contained elaborate greetings and expressions of sentiment, tended to evade issues that might cause offence, expressed important points with subtlety, and hopped from one topic to another. This would help British policymakers and officials to argue subsequently that the correspondence was “ambiguous and inconclusive”. Yet when clarity was needed it was there.

The very first letter set out clearly the demand for “England to acknowledge the independence of the Arab countries” and contained a precise geographical description of the areas Hussein considered those countries to cover. The thinking behind the crucial paragraphs that set this out had originated among Arab nationalists in Greater Syria (which included Palestine) and Iraq. But the Sharif’s demand put the High Commissioner and his superiors in London on the spot. What attitude should imperial Britain take to a new, potentially powerful, Arab state made up of the Arab areas of the Ottoman Empire?

MacMahon could not read Arabic, so he dealt with the letters from the Sharif in English translations and drafted his replies in English for translation into Arabic (the Sharif could not read or speak English). He initially side-stepped the issue of Arab independence, hoping it would go away, but received a polite rebuke which referred to the High Commissioner’s ambiguity and his “tone of coldness and hesitation with regard to our essential point”.

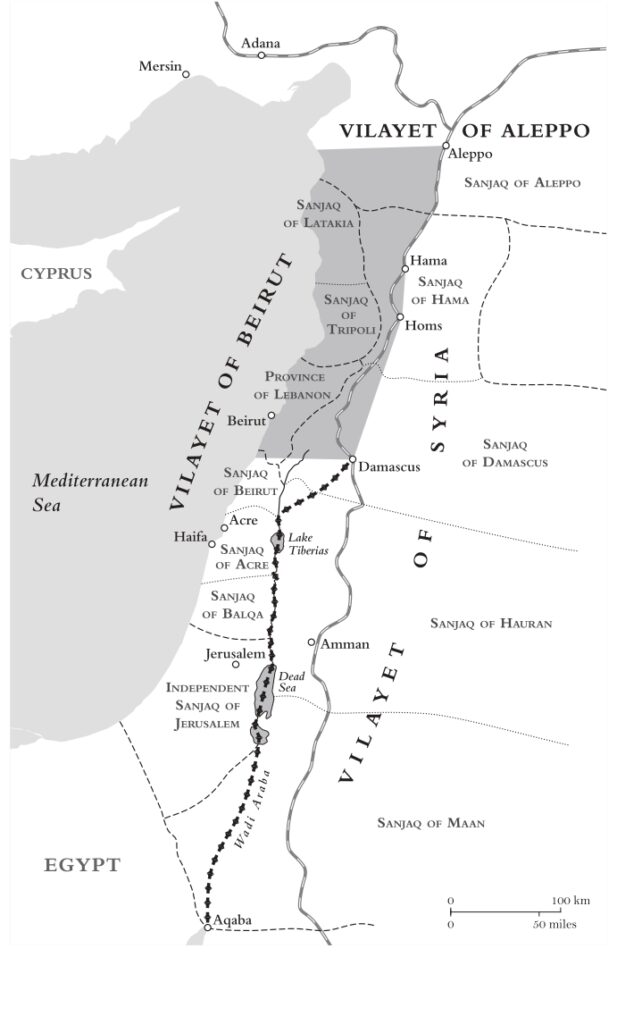

The following letters included a polite haggle over which areas Britain would recognise as intended for the future Arab state. On 24 October 1915, MacMahon set out certain limitations on British recognition of the Arab claims. The limitation that is relevant to Palestine was his statement that “…portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded [for the Arab state].” For his part, the Sharif was adamant that these “portions of Syria” were Arab. He reserved his position, stating that once the war was won he would renew his claims to these areas. The parties agreed to disagree, and he rose up against the Turks.

In 1917-8, Britain drove the Turks out of Palestine. British aircraft dropped leaflets in Arabic saying that Britain had promised the Arabs independence. Some or all of the leaflets included a picture of the Sharif Hussein. Recruitment of soldiers for the Sharifian army proceeded in areas of Palestine once they were under British occupation.

When Britain decided to implement the 1917 Balfour Declaration in Palestine, Palestinians and other Arabs argued that Palestine had a right of self-determination based on Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations as well as natural law. They also referred to the Hussein-MacMahon correspondence and to Britain’s pledge in that correspondence. They drew attention to the fact that Palestine did not lie “to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo”, and asserted that Britain had thus recognised Palestine as an Arab country. Jews would be welcome in Palestine, they stressed, but they would not be allowed to take over the country, which was the goal of the Zionist movement. Britain might have agreed to facilitate such a take-over in the Balfour Declaration, but it had had no right to do so.

So where exactly is Palestine?

is represented by the shaded area (roughly Lebanon). The thick line running from Damascus southwards to Aqaba represents the Foreign Office’s 1920 (invented) western boundary of a fictitious ‘District of Damascus’, officially adopted by Churchill in 1922.

British representatives denied that Britain had recognised Palestine as being in the area for the putative Arab state. They asserted that it did, in fact, lie to the west of the “district” of Damascus. The Arabic word which MacMahon’s colleagues used to translate “district” into Arabic was wilayah. This Arabic word had passed into Ottoman Turkish as vilayet which was the official word used for a “province” of the empire. There was an Ottoman vilayet of Syria. This was not coterminous with the modern state of Syria, but had its administrative capital in Damascus and extended east of the Jordan and south all the way to the Gulf of Aqaba. This was indisputably to the east of Palestine. On this logic, Britain claimed that it had excluded Palestine from the area it acknowledged as belonging to the proposed Arab state. However, in Arabic wilayah did not carry such a closely defined meaning as vilayet did in the Ottoman administrative structure. As an expert from SOAS would point out in 1939, wilayah could mean “district” or “area” or “the seat of a governor”.

The book is divided into eight chapters, a conclusion and an epilogue. Chapter One: West of the Line of the Four Towns (1915-19) sets the scene and tells the story of the Sharif Hussein and Sir Henry MacMahon, as well as other essential matters such as the Balfour Declaration and British agreements with the French. One of its most interesting sections sets out no less than nine occasions during this period when important British figures (including MacMahon and the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George) indicated in internal British documents, at least by implication and sometimes explicitly, that what would become known as the Arab interpretation was correct. Chapter Two: League of Victors 1919 continues the story with the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the new concept of a League of Nations mandate, the unequal diplomatic tussle between the Zionist movement and Arab nationalists over Palestine, and the early stages of the betrayal of Arab rights and aspirations.

Chapter Three: Detrimental to the Public Interest (1920-24) deals with the establishment of the British Mandate over Palestine, the partitioning of the Ottoman Arab provinces by Britain and France, and the destruction by France, with British connivance, of the embryonic democratic and constitutional monarchy of Arab Greater Syria. It also shows the appearance in 1920 for the very first time of what became the British interpretation of the correspondence.

This was contained in a memorandum written by a Major Hugo Young, who had joined the Foreign Office the previous year on the recommendation of Lloyd George. Yet when Young and his boss, the assistant secretary of state, tried to persuade Prince Feisal, the son of the Sharif Hussein, of its new interpretation, the prince responded immediately by pointing out that there were no vilayets of Homs or Hama, and therefore the word in the original Arabic text could not have been intended to refer to Ottoman provinces. The records of the meeting show that Young had no answer to this. Nevertheless, the new interpretation was now adopted by British policy makers. Unsurprisingly, publication of the official text of the letters was refused, since it was deemed by the British officials to be “detrimental to the public interest”.

Four: Non Possumus [Latin for “we cannot”, or “here we stand”] (1924-38) covers the middle years of Britain’s mandate over Palestine. From the time of the 1929 riots if not before, British politicians and officials became increasingly concerned at the turn events in Palestine were taking. They felt unable to square the circle British policy had created by denying self-determination to the Palestinian people in order to implement the Balfour Declaration. This feeling increased exponentially after the outbreak of the Palestine rebellion in 1936, the Peel Commission’s partition proposal in Chapter 1937, and Britain’s abandonment of that proposal.

Britain’s interpretation just does not stand up

Chapter Five: Abandoning ‘Vilayets’ (1938-9) shows how Britain was finally forced to abandon its argument as unsustainable. This was against the background of the storm clouds then gathering over Europe and British fears of losing Arab support when war came. What now preoccupied Britain’s policy makers in the Middle East was the need to show that Britain had behaved in good faith, that its intention to exclude Palestine in the correspondence had always been clear, and that it was just unfortunate that the Sharif had not realised that. This, as they knew full well, would be difficult to demonstrate.

Chapter Six: Correspondence in the Conferences (1939) and Chapter Seven: Anglo-Arab Report (1939) deal with the preparations for the 1939 St James’s conferences on Palestine and the conferences themselves. Separate conferences were held by the British representatives with the Arab and Zionist delegations. Dr Shambrook’s focus is on the proceedings involving the Arab delegation, since it was in the meetings with them that the pledges to the Sharif Hussein were discussed. The British representatives were quickly put on the back foot, and did not recover. Both Lord Maugham (the Lord Chancellor), who was dragooned onto the British delegation to provide heavy-weight legal support, and the Attorney-General (Sir Donald Somervell) were forced to admit in internal British documents that the British interpretation was so weak that it would not stand up to judicial scrutiny. The reader is left with the impression that Lord Maugham suffered severe personal embarrassment as a result of the role he had been asked to play.

Dr Shambrook dissects in a succinct but masterful way the agreed joint Anglo-Arab report on the correspondence. It stated that the parties had failed to reach agreement; but Britain made significant admissions. The Arab contentions “had greater force than has hitherto appeared.” Britain acknowledged that Palestine was in the area claimed by the Sharif and that unless it was subsequently excluded “it must be regarded as having been included in the area in which Great Britain was to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs”. Although Britain still maintained that it considered it had excluded Palestine, it did agree that “the language in which its exclusion was expressed was not so specific and unmistakeable as it was thought to be at the time.” At Arab insistence, Britain also undertook to publish the correspondence.

The Anglo-Arab report was a fudge. Dr Shambrook describes it in the Conclusion as a whitewash. Yet he also points out that the Arabs had won a moral victory, and knew Britain too well to expect a complete climb down. There seems little doubt that the weakness of Britain’s case on the Hussein-MacMahon correspondence was a factor in the change in policy contained in the 1939 Palestine White Paper. Britain’s policy finally shifted towards making Palestine independent as a unitary state with democratic institutions in which the rights of the Arab majority and Jewish minority would be safeguarded. This would lead to an insurrection by the armed forces of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, in order to create an ethnically Jewish state by force of arms. Britain renounced its Mandate in 1947 and departed the following year, abandoning Palestine to a state of chaos and war. But all that is outside the scope of Dr Shambrook’s excellent book.

Chapter Eight: Discordant Historiography 1938 is the final substantive chapter and deals with the way academic debate has looked into the controversy since it was last considered in detail by HMG in 1939. It highlights important failings in the scholarship of those who have endeavoured to sustain the British interpretation. This is especially the case with the writings on the topic by Elie Kedourie and Isaiah Friedman.

Dr Shambrook ends with an appeal for an acknowledgment by Britain of the truth, and points out such an acknowledgment might help heal the wounds of history. Policy of Deceit is absolutely damning of the dishonesty of British policy over Palestine. The British Government marked the centenary of the Balfour Declaration in 2017, but remains shamefully silent on the prior commitments MacMahon had made on Britain’s behalf, with the approval of Whitehall.

It is now surely time for Britain to set the record straight.

John McHugo is a trustee of the Balfour Project and a board member of CAABU. He is the author of three books about the history of the Middle East. A revised and updated third edition of his A Concise History of the the Arabs will appear this Autumn.