Online talk given in March 2022.

Ali Awad is a 22 year-old activist from the village of Tuba in the South Hebron Hills.

Becca Strober is a former soldier originally from Philadelphia. She is the Director of Education at Breaking the Silence

Related Links

A segment, which you can watch at this link, shows what everyday life under occupation in Area C looks like: military training exercises inside Palestinian villages, settler violence against Palestinians, expansion of unauthorized illegal outposts, home demolitions, and more.

Watch this 4-minute video from Breaking the Silence about IDF Firing Zone 918. Personal Stories:SaveMasaferYatta – Photo Essays,

Watch this 8-minute video from Social TV that paints a picture of life in that village of Tuba

The Breaking the Silence report on Discriminatory Policies of KKL-JNF

Ali Awad’s recent pieces in Haaretz

Why Israeli Settlers Are Targeting Palestinian Kids’ Playgrounds

For 17 Years, Stone-throwing Settlers Have Terrorized Palestinian Children. I Was One of Them

Matan Rosenstrauch:

My name is Matan and I coordinate the Balfour Project Peace Advocacy Fellowship. We have 12 post-graduate students who are working on different campaigning and projects. This webinar actually is part of one of this year’s project of Pyla, Douglas and Maya who, when thinking what can we do from the UK to promote equal rights? One of the answers that we came up with is to try put international pressure to prevent expulsion of Palestinians living in Area C. And this is why we are here today. Breaking the Silence is such an inspiring organisation for people who, like me, went to the army and saw that the army of defence is an army of occupation and documents this, but also does a lot of work human rights work in the South Hebron Hills. And this is why we’re going to hear about the situation in Masafer Yatta today. So thank you everyone for joining, and I’ll hand over to Becca.

Becca Strober:

Thanks so much Matan and Diana for hosting us from the Balfour Project. I think I can speak for Ali and myself when I say that we’re happy to be here and shed some light onto the situation of Yatta and the firing zone. And I’ll say briefly that my name is Becca Strober and I’m the Director of Education at Breaking the Silence. We are an organisation of former soldiers who served in the occupied territories. So the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza, and we then collect testimonies from fellow soldiers who served in these areas. We verify these testimonies and we use them as the base of our educational work, which is today is a great example of some of the educational work that we do. And we give tours in Hebron, in the South Hebron Hills, and Masafer Yatta is part of the area of the South Hebron Hills.

Ali is a very good partner of ours, who’s going to be able to speak from personal experience of what it means to live inside a firing zone and how that’s affected his own life and the life of his family and other villages.

And so I’m going just start us off with a little bit of information of what are we talking about today. How do we get to the situation that we’re in today, and then I’ll hand it over to Ali to talk from his perspective about the situation.

I’ll just start by saying that we’re really happy to be doing this right now, because there was just another court case about the firing zone about 10 days ago on March 15th. So what we’re talking about today is really, really relevant to right now, and there’s a lot that we can do right now.

This isn’t a moment in history. It’s not something theoretical. This is a real issue that’s affecting the lives of 1,300 people, including Ali and his family and many others.

And so today we’re talking about Masafer Yatta, which means the periphery of Yatta and Yatta is a big city in the South Hebron Hills.

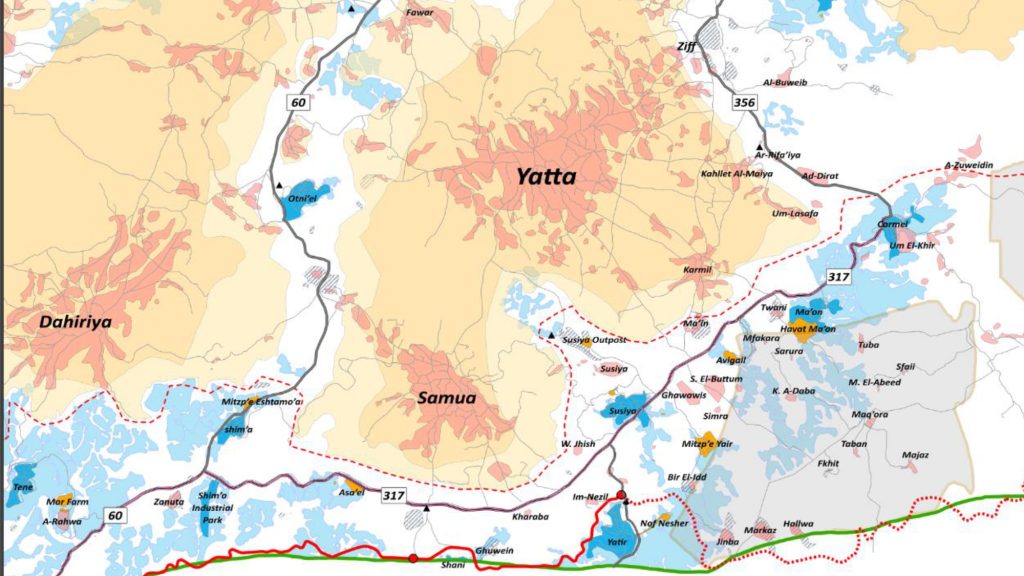

Here is the city of Yatta today. There’s about 120,000 people who live Yatta. And in this area that you can see is boxed out, there are 12 villages inside of this area in what’s called Masafer Yatta. And that is the line that we see of the firing zone. It makes up about 30,000 dunums. So we’re talking about a lot of land and the lives of 12 villages today. And I’m sure Ali can expand on this from his own experience and his own family stories.

But I’ll just say briefly that Palestinians began living around the area over 200 years ago, early 19th century, settling on the land that had been used for grazing by residents of Yatta. Because people would live in Yatta, but pushed by the favorable climate in the area and cheaper land families from the city of Yatta started moving out into the area and worked in farming and shepherding. And at first people were living there in the area seasonally, but as time progressed, their residents in Mussafer Yatta became year round. And that’s an important thing to note because when we talk a little bit later about the court case that’s going on today, the concept of do these residents live their year round or not is relevant and of course the answer is that they do, and they have for a long time.

As families moved to the area they renovated or dug new caves. There are natural caves in the land that offer a great option to live in because they stay cool during the hot summers. They stay fairly warm during the cold winters. And many have lived in the same area, same caves, or built on top of them for generations.

And the residents continue to maintain a fairly traditional lifestyle to this day of farming and shepherding and making their money through agriculture.

And so it begs the question. There are 12 villages here, people live there, how does this become a firing zone? How does this process even start?

And here is just an example of a village today inside Masafer Yatta. And as you can maybe see, we’re looking at an area that’s more or less, the climate is a desert. If you actually were to go out there right now, there’s a lot of grass. In fact, there’s a huge wildfire bloom that I saw yesterday in the area, but a lot of the time of the year, it doesn’t get a lot of rain.

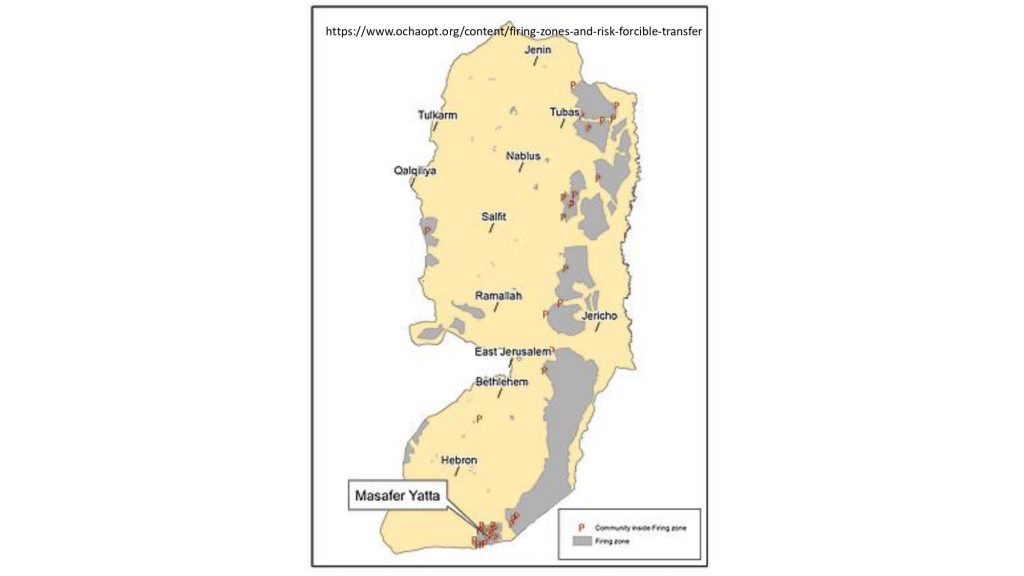

And so if we just take a really quick look at a map of Israel and the West Bank and the Gaza strip, and, and we look specifically at the area of the West Bank in 1967. Israel occupies the West Bank, and there’s one guy named Gal Alon. He’s a cabinet member, he’s a military general. And he seeks to annex the eastern part of the West Bank to Israel. And as you can see the eastern side, it includes the city of Jericho, but otherwise it’s a pretty rural area.

And though this plan has never been voted upon many facts on the grounds have been laid out in order to actually carry out this plan in reality. And as part of that in the early 1980s, vast swaths of eastern lands of the West Bank are declared firing zones, which prevents residents from being able to stay in the area and develop the area and continue living there in a way that makes sense is profitable and is sustainable for them.

And I know the slide that I’m showing you is in Hebrew, and I’m assuming most of you don’t read it. But I’m showing in anyway, just as an example of that Ariel Sharon, who was a member of the government in 1981 actually said in a meeting that had later been uncovered by the group Akavot, which you can see on the bottom left, that the point of placing these firing zones in the eastern of the West Bank is to prevent or restrict expansion of Arab villagers in the area. He suggests doing this and it becomes a permanent plan in the early 1980s.

And here you can see the, this is the Eastern side of the West Bank and here are all of the firing zones that were declared in the early 1980s.

I mentioned the Alon Plan seeks to annex the eastern part of the West Bank into Israel. And this declaration of firing zones goes hand in hand with this concept all throughout the eastern side.

And if you look at the bottom where it says Masafer Yatta, these are the communities that we’re talking about today.

And so what happens since then? The 918 firing zone, the firing zone that we’re talking about today, is officially put together and declared in 1983 when it conjoins two firing zones that had been separately created. And nothing really happens in the 1980s. Nothing really happens in the 1990s, the Palestinian communities in these area, the 12 villages already have a much harder time being able to develop because the Israeli army doesn’t allow them to develop because what we’re talking about is a firing zone.

I didn’t mention it because to me it sounds so obvious that I realise it’s not that when we’re talking about a firing zone, we’re talking about an area of land where the Israeli army practices with tanks, with guns with major weapons. In August and November of 1999, most of the inhabitants of the 12 villages are basically served by the army evacuation orders for legally dwelling in a firing zone, even though they’ve lived there for centuries before.

On November 16th, 1999, about 23 years ago, Israeli military forcibly removes over 700 residents. The Israeli army then went and destroyed homes, destroyed or are watering holes where rain had been collected, confiscated property. And the villagers are at this point, dispossessed of their lands and of their livelihoods and are left homeless.

And in 2000, the court allows the communities to return to their homes until a final decision is reached. That was in 2000. Today, we’re on March 24th, 2022. And it’s now been 22 years since that initial temporary decision and the residents and the villages are still living in legal limbo. There has yet to been a final decision.

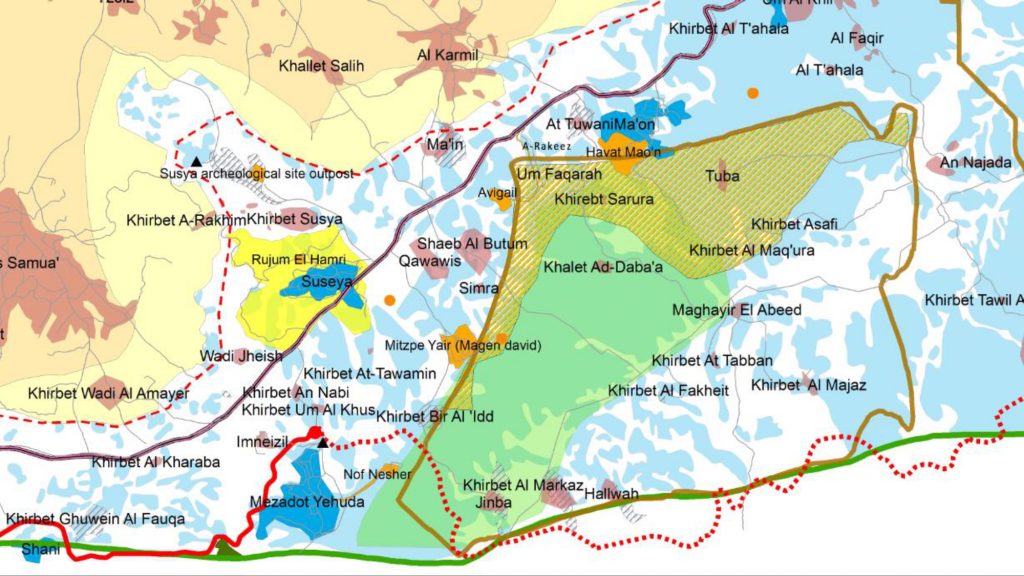

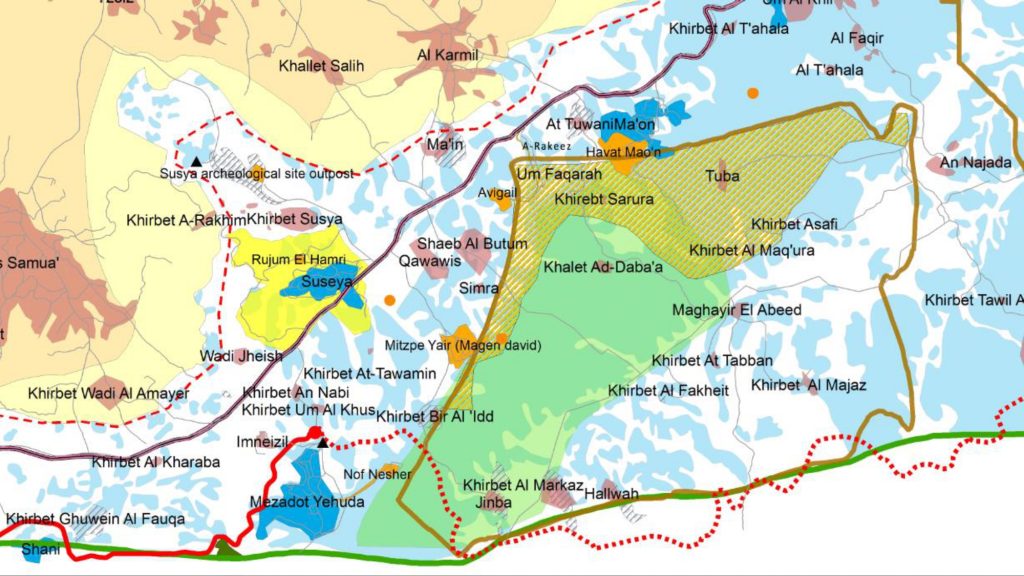

And this is a map of the area of the firing zone 918. Tuba is the village that Ali’s from. So I’m sure he’ll speak about it more specifically. And some of the other well known villages are Mufaqara, which was a village that was attacked in October by around 80 settlers. And we’re happy to talk more about the settler violence that affects the area in the question and answer section.

What’s been going on the past 22 years and what can we do about it? And then I’ll hand it over to Ali.

And so even though the residents of these 12 villages are allowed to return, from that moment, and until today they’re living under threat of constant expulsion since then. Although the eviction proceedings cannot advance until the Supreme Court case is resolved, meaning until they make a final decision. And that’s what they talked about in the court hearing on March 15th, just 10 days ago.

Even though nothing can be decided until the Supreme court decides, we’re talking about an Area Called Area C, In the West Bank, there’s Areas A, B and C. What’s important to know is that Area C, which makes up 60% of the West Bank and all of the firing zones, including 918 are in Area C, Area C is under the direct responsibility and control of the Israeli military. That means that there are soldiers on the ground at any time who are dealing with issues sometimes related to security sometimes not, but also that is the Israeli military, and specifically a group called the civil administration who are responsible for giving building permits, permit infrastructure, permits for building schools, permits for being connected to the grid, to electricity, to water. All of these things are under the direct responsibility of the Israeli army.

And so because these 12 villages are in a firing zone, even though there hasn’t been a permanent decision, that means that it’s the Israeli Army’s responsibility to give them access to all of these things until a permanent decision is made. But what we see in reality is that the army says because they’re in a firing zone, they’re not able to have access to any of those basic needs. And so that means that it’s impossible to build structures in the area such as toilets, such as repairing water systems, such as community centres, such as schools.

Some of those things do exist inside the firing zone, but if they exist and they’ve been built anytime after 1967, that means they have demolition orders on them because they weren’t given approval by the Israeli military to be built. And there is no way that the Israeli military will give approval.

Only 2% of requests in Area C are actually given to villages and to residents to build. And in addition to that, something else that I think is important to understand from our position, especially as former soldiers, is that although live fire is not used in this firing zone, because the case is still pending, the area’s status as a firing zone gives it additional challenges. Even military training without live ammunition takes place in the area and it causes damage to land. It causes damage to property.

And as part of standard training for one brigade, called the Nahel Brigade, soldiers drive in regularly in armored protected carriers. And they go through residents’ wheat fields. Now these are areas, these are communities who live off of agriculture. What happens when we practice in those areas? And this is an example of a training that is happening near people’s homes.

And you can see the kids looking out as the soldiers are training. And I just want to share one example of a testimony that a soldier shared with us in 2004 of training in this area. And he says, “we were driving during APC week,” which is a week in which they learn advanced training course for infantry soldiers on how to use armored personal carriers. And he says, “suddenly we’ve realised, I can’t remember if I realised or someone else that we’re driving on wheat fields. I asked my friend what’s going on because it’s still basic training and you can’t talk to the commander. He also didn’t know. He asked, and then we were told offhandedly that Bedouins are taking over the military’s firing zones. So there’s an instruction from the battalion commander. I think I didn’t understand the term so well back then, but we train on their fields in any case.”

In addition to that in as part of the firing zones we also carry out raids and searches in villages. One really good example of that is the village of Jinba. And it’s a really good example because, though you can’t see it on the map, right below it, there is an infantry base and when soldiers are finishing up advanced training at times, and we have multiple testimonies on this, the village that this group raid, may it be for practicing, or may it be for searching for military equipment. It either way, of course, that has a huge, real and psychological effect on the people living there, including children.

And one more thing that I just want to mention before we talk a little bit about the legal arguments is that all of these questions are partially happening because it’s a firing zone. And, but according to Keram Nevot, which is a well known Israeli human rights organisation that documents land use in the West Bank, 18% of the West Bank is designated at firing zones. It’s a pretty big amount, 18%. And yet within this 18% that’s used as firing zones, only 20% of that land actually actively being used for military training. And in firing zone 918, Masafer Yatta, the area that we’re talking about. Only about 1000 dunams of the 30,000 dunams area of the firing zone is actively being used for military training. And this follows the need for the Israeli military to take over this area and expel Palestinians from their homes being even harder to justify.

And I think that brings us to the question of what is the justification of the military.

Diana Safieh:

We had some questions about that map Amelia Mills asks what the different colours mean.

Becca:

So I’m assuming at this point we understand the brownish frame that we see that is the area of the firing zone 918, also known locally Masafer Yatta. The green that you see are nature reserves. And so you can see that there are layers here of things that have been declared. The nature reserve has been declared on top of the firing zone. And then you see that there’s white and there’s blue. Now this is according to the states. It’s not according to the papers that Palestinian residents hold, but according to the state, the area that’s white is private land and belonging to Palestinian residents. And the areas that are blue are a public land, or as Israel calls them state land. And that’s an important differentiation because public land is a term that every single country that I know of you uses. It’s a land that serves the public. Israel takes it a step farther and calls these stand state lands, which means even though Israel is not the sovereignty of this area, we’re talking about a Palestinian public by declaring them state lands Israel, the Israeli state and courts then justify that these lands for Israeli needs as well.

The other things that we’re seeing on this map outside mainly of the firing zone, what you can see in blue are Israeli settlements. They were set up in the 1980s around the same time that the firing zone was declared. The Alon Plan is starting to be carried out in the 1980s. And there’s multiple tactics that are being used, declaring firing zones and setting up Israeli settlements in the area.

And then the orange that we see is areas that are illegal outposts. Now the differentiation between settlements and outposts are that by Israeli law, settlements are legal and we’re built before the Oslo Accord. So before 1995, while as illegal outposts or illegal also by Israeli law, meaning they don’t have a master plan, it’s illegal to connect them to water. It’s illegal to connect them to an electricity, both are illegal and international law. And we are signed on the Fourth Geneva Convention saying that we’re not allowed under the laws of occupation to transfer the occupying civilian population into occupied land.

I will just say one more thing about app post is that even though it’s illegal to connect them, it’s illegal for them to be there. And yet these outposts for the most part, absolutely are connected to water, to electricity and have access to infrastructure.

And then the small dots that we see are individual farms and maybe Ali you can speak of that a bit more from your experience. They’re basically individual farms that have been set up in the past few years where there’s only one or two rarely settlers living there, but they’re living in places that are so strategic that they can actively attack all of the Palestinian residents of the area as they go out to graze their sheep and goats and, and settler violence is one of the tools that we see to kick the people out of the area. Maybe Ali will talk about that a bit more, but I do want to focus on one of the other methods that we’re talking about, which is declaring something firing zone.

So again, just 10 days ago, March 15th, there was another court hearing and that court hearing still has not led to a final decision. This whole process began in 2012. And the state has maintained throughout this time that its position that they support expelling the village residents, including Ali and his family because they are not permanent residents according to the state. This is despite the fact that there are actually pictures, aerial photos during the time of the British Mandate from the 1920s, that actually show of these villages such as Jinba and Malka on the British Mandate maps.

And this is despite the fact that there’s other proof and that the villages have been able to show to the high courts that show that they’ve been living there permanently since before 1967, since before the occupation of this area and even longer.

So that’s one reason why they say it’s not a problem to practice in this area because the residents aren’t permanent residents. Even though the residents and the proof show otherwise.

The other thing is that in 2012, the courts made a change. The army made two comments to the courts in 2012. The first was that they said, we need the firing zone because the firing zone looks and feels similar to Southern Lebanon and in the war in 2006, that Israel had with Southern Lebanon, with Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon, soldiers performed poorly. And so they need to practice.

I have two points about that. The first is that when I was in the army between 2000 and 2010, I actually lived on a kibbutz that was 100 meters from the border of Southern Lebanon. And this area that you saw a few pictures of is a desert area, looks nothing like Southern Lebanon.

The other more important aspect of it is that occupation is legal, as long as it’s temporary. I’m not saying it’s moral, but it’s legal as long as it’s temporary under international law.

However, you can only seize land for immediate security means, meaning it’s illegal by international law to use land in occupied territory in order to prepare soldiers for a war with a different country.

The other thing that the army said in 2012 is actually, we only need to practice on some of the land doing a wet practice, and a wet practice is what we call in the army when you’re using live fire, using live bullets, but dry practice doesn’t use live fire.

And on the map, you can see there’s this yellow lined area that I didn’t discuss yet. Tuba’s in there, Faqara is in there. There are four villages that are in this area. Then in 2012, they say these residents don’t need to leave. They’re no longer at risk of expulsion, according to the army needs. However, they’re still at risk of their homes being demolished because they’re in a firing zone, they still can’t develop.

But what is interesting to note is the same exact areas that were declared in the dry zone are the same exact areas where Israeli illegal outposts have land inside the firing zone. So Havat Ma’on and Avigail and Mitzpe Yair all have land inside the firing zone. Is it a coincidence that specifically this area was declared an area that is only going to have dry practice on it? I’ll let you answer that for yourself.

And so these are the main arguments that the army is making as to why we even need those areas.

What I want to say about the court case before I hand it over to Ali is a few things. The situation as it stands at right now is that the courts, when it comes to the occupation, doesn’t like to make decisions that are essential. And that could be decisions that are then the basis of a legal precedent for other decisions. And that’s seemingly one of the reasons why this court case gone on for 22 years.

But we’re not just talking about a court case. We’re talking about people’s lives, people living in legal limbo, being unable to develop, unable, to build, unable to add infrastructure. It’s not a joke. It’s not a theoretical thing. These are people. And, so what the court is aimed to do is try and basic the bridge between the army and the residents.

And one of the most likely outcomes that the court is going to go with is what the army suggested most recently, which was that they won’t kick the residents out for forever indefinitely, but rather every six months, the army will have the right to require residents to leave for 15 weeks of every six months.

But who is going then to deal with housing for the residents? And of course, what about agriculture? If anyone here works in agriculture, people understand that when we’re talking about 15 weeks during an agricultural season, that is the agricultural season sometimes. How are people intended to make money, to uphold their lives, to send their children to school, if for 15 weeks they can’t access their homes nor their land.

And so the residents have rejected this option, but it seems likely either way that the courts are going to go with either this option or an option similar. It’s important to note that the legal question at hand is not, does this or does this not really need to be a firing zone at this point? The legal question at hand is do the Palestinian residents of these 12 villages, 1,300 people, have the right to live on their land or not. And that’s a fundamentally flawed question, but there’s a lot that we can do. We can, before a verdict is into is issued, which we believe might happen in the next two months. It’s crucial to raise the profile this case. And that’s what we’re doing here today with you. And I encourage everyone to be active in this issue.

Any intervention is going to be good at this point. We need more people to know about Masafer Yatta and the firing zone.

But even after a verdict has been issued, if it says that the residents can be expelled temporarily, it’s important to remember, they’re not going to be expelled the next day, and that it’s relevant to keep putting pressure on this issue and keep highlighting this issue, because that’s an opportunity to put pressure on the government to not expel the residents at any point.

And the last thing I want to say, and then I’ll hand it over to Ali, is this case is super important. Not only because of the 1,300 people living here, though, that in and of itself is incredibly important, but because it’s the first case of firing zones to make it to the high courts. And whatever’s decided here is likely to affect not only this firing zone, but every other firing zone in the West Bank, which is 18% of the whole entire area and affects thousands and thousands of people.

And so I believe that as someone who once served the system, the only moral thing we can do is to resist it and to put pressure and stand with the 1,300 people who are potentially going to be expelled from the lands that they’ve lived on for hundreds of years. And I’ll hand it over to Ali.

Ali Awad:

Thank you so much for this wonderful explanation. I will talk about the situation but also what my family have experienced living under those policies in this area. So first of all, my name is Ali Awad. I am a master student and activist from the village of Tuba, one of the 12 villages that was declared by the Israeli Army as a fire zone in the eighties.

I was born and raised in the village Toba. This land Masafer Yatta, as Becca was talking about, is our only homeland. My father was born in Tuba in 1942 and he inherited our land from his great grandfather. My family has been living in Masafer Yatta for more than two centuries.

We did not move here because of the occupation from another place. But actually this is our only home even before the occupation and before the existence of the state of Israel in 1948. But my grandfather was living in Masafer Yatta, in the caves and also raising livestock and cultivating the land, suddenly after 1967, he found himself actually dealing with a policies by the Israeli occupation that aims to evacuate him from his land.

First of all, it started since the Israeli army arrived to the South Hebron Hills and to the area of Masafer Yatta and have built the military basis on the Hills. Those Hills are the places where our sheep graze. We depend on the livestock as the only livelihood for ourselves and for the whole families in Masafer Yatta.

So taking away like the land either for the benefit of the settlements or for the benefits of the military is another policy to push us like in indirect way out of our homes so that we lose our livelihood so that we leave our villages. So it’s an indirect policy. The direct policy is actually the declaration of the filing zone. In my own perspective and what my family have passed through, I believe that the firing zone declaration is only an excuse to say that we are living in a firing zone and to legally evacuate us from our homes.

So what would happen if the 1,300 people will be evacuated from their homes? And if the court will give a decision in the favour of the army and to decide to displace this 1,300 people. The experience that my family lived in 1999, that year I was just one year old, but my grandfather, tells me about the harsh experience that they have lived.

It was during the winter time in Palestine. They evacuated us out of Tuba. And then my family moved and built a few tents to stay there in hope of returning while working on the legal action to come back home. Those tents, one tent for the sheep. And one tent for a family of 29 members.

Also the sheep, as I said, the livestock were the only livelihood for the people here is, was the time to give the birth. So in this temporary camp that my family lived away from Tuba, just four kilometers away from tuba, also the civil administration and the Israeli army, as Becca said, the civil administration is the army of the Israeli army that control the Palestinians in Area C. So they showed up at our camp and confiscated all our tents. So in that rainy night, my family stayed like homeless. They even confiscated the food of the sheep. Luckily one relative from the city of Yatta rushed with a tent to build for the family. But for the sheep, they stayed outside in the open. And in the morning, my grandfather told me that he found 30 newborn lambs were dead frozen.

And they continued in this way for several months, without any home and without any settled life until they come back with an interim injunction in the year 2000. However, until today we are living under the threat of expulsion and under the threat of evacuation. We are considered in Area C, and any master plan for a village that for a Palestinian village in Area C should be approved by the civil administration. According to OCHA, 98% of the plans submitted to the civil administration are rejected.

In the whole area of the South Hebron Hills, there are just two villages that have a master plan in particular area. For my village, it was declared as a firing zone and it is in Area C. So anything, even schools and medical clinics, it’s considered by the civil administration as illegal and as subject of the demolition.

So here in Masafer Yatta, the civil administration is very active, weekly distributing the demolition orders in the homes and infrastructure that the people try to build. like main shelters for their families, because the families are expanded every like every year. And they need like new generation are getting married and they have Masafer Yatta as their only home. And they need to build the new houses and those in new houses, either in every week, there is a distribution of home demolition against the residents of 1,300 residents in Masafer Yatta, or there will be an actual home demolition or not just the home demolition of the human beings, but also against the sheep and the water cisterns.

Not having a master plan doesn’t just mean that the home would be demolitioned, but also any attempt of building the main services that the residents will need are subject of the demolition and prohibited. For example, my village, it’s not allowed to be connected to the water or to the electricity. I show you the only road that leads to my village, normal cars can’t even drive there.

The other policy is the settlements, those military bases that arrived in 1967 after occupying the West Bank in the eighties in a clear violation to international law, Israel is using its civilians as settlers in the occupied territories. So they transferred those military bases into residential neighbourhoods in order to bring Israeli civilians as settlers in the occupied West Bank. So those settlements are a few hundred meters away from my village.

As Becca showed, to the south of my village, it’s Israel, where we, as Palestinians, are not allowed to go. And from the other side, there is a chain of settlements that separate my village from the rest of the West Bank.

In order to keep expanding the settlements, they enforced the so-called the state land law, which actually it’s a law that was implemented here in Palestine during the Ottoman time. If the person doesn’t use his land for a few years, then this land will transfer to the public benefits.

Israel actually is using this law for colonialism, because what it does, it implements it in the territories in order to expand its settlements, the agricultural outposts here.

So here in Palestine, people in Mussafer Yatt use part of the land for plantation and the other part, which is stony, they use it for grazing. Even the Ottoman Empire law said grazing is using it. You are using your land, even if you just graze in it and you don’t plant it. So most of the hills around Masafer Yatta were declared as a state land. Then the state has the right to lease this land for whoever the state wants. Which means the state of Israel here the military occupation in occupied territories here, what they do actually is they lease it to the settlers in order to build agricultural outposts. There are seven of them in Masafer Yatta and the whole area of the South Hebron Hills which have started since 2020.

They are making a chain around my village. Last year, we lost tens of thousands of dunums of land that we are not allowed to graze on anymore. It’s because of the control and the settler violence that comes from the settlers who establish those outposts.

I just want to say briefly, focusing about the firing zone, now they are evacuating those eight out of the 12 that were declared. My village, since 2012, they said that we can stay. It’s not because they don’t want to evacuate us, like the rest of the residents in the other eight villages, but because it’s located next to Israeli illegal outpost inside the firing zone.

They don’t want to remove any outpost, those are considered as illegal, even in the Israeli law, but they are connected with paved roads and electricity and water. But still, they are saying, for example, in my village, that is that they said that we can stay, but any home that was built after 2012, it must be demolished. So for example, in my village, there are around 12 structures that we built, even some of them before 2012, but the civil administration claimed that it was after. So it’s under the threat of demolition and it was connected to the main case of the other eight villages. So my village next to the legal outpost in the firing zone will be connected to the main file of evacuating Palestinian villages. But the Israeli illegal outpost will not be hurt in any way.

I’m thankful for everyone that showed up to listen to the story here. And we ask you to visit the website that we are making, www.savemasaferyatta.com

And we are asking you to stand up against this ethnic cleansing that will make 1,300 people, including myself and my cousins and little children be without homes, without livelihoods. We are asking you to stand up against this apartheid and this ethnic cleansing. And thank you so much.

Diana:

Thank you so much, both of you that was fascinating and heartbreaking. We do have a couple of people talking about what Ali literally said in his last comment about whether these tactics could be described as ethnic cleansing. I don’t if you want to comment on that, Ali already did.

Becca:

At the end of the day, what we describe is the reality and the reality is the pressure that the state is putting on these areas to get them to leave Area C and move into area a, which is basically big Palestinian cities. Leave Masafer Yatta and move to Yatta. There are a lot of terms that you can use for it, but I think regardless, it’s something that we have to band together and stop. That’s totally immoral. regardless of whichever legal term you use to call it. There’s nothing that can morally it justify kicking 1,300 people out of their home, regardless if the courts say we’re talking about a temporary situation, there’s nothing temporary about that.

These are people’s lives.

Diana: This case is setting a precedent full or what might come for a bunch of other communities in the same absolutely situation. So it could be have further reaching consequences. Got a question from Amelia Mills, the green area, the national parks that you were showing on the maps, have they been created by the Jewish National fFund?

Becca:

I don’t wanna misspeak. There’s two options. One is the Jewish National Fund, and there are Jewish National Fund areas that have been built in the West Bank. If you take a look for example, Havat Ma’on, which is an unauthorised outpost and someone asks, what are the names of these unauthorised outposts? You can see Havat Ma’on, Avigail, anything that you see in orange. Havat Ma’on is built on a JNF forest. The other option is an Israeli National Forest, meaning there are multiple, and I believe it’s that, I believe it’s not a JNF forest, , I’m happy to look it up and send it.

Diana:

I suspect her reason for asking, and maybe I’m wrong here is because the Jewish national fund obviously is considered by many as legitimate organisation that gets funding here in the UK. And if it is involved in something that is considered illegal by international standards, then that would be unusual.

Becca:

Absolutely, the JNF is working in the West Bank. There was recently published research about how involved the JNF is in the West Bank.

Diana:

So we’ve got from Sandra Hamrouni is one of the Balfour Project executive committee members and who worked with the British Council over there. She says when I worked there, I saw illegal settlements with swimming pools, electric lights for roses that were going to be sold in Europe. Whereas Palestinians had no access to water or electricity. Can you say something about the comparative use of resources by Palestinians and by the settlers?

Ali:

Like in Area C, for example, Palestinians are not allowed at all to connect to water, except for those villages who get like a master plan. They will get a water from the Israeli company called Mekorot. So, for example, according to Oslo Accords between the Palestinian Liberian Organisation and Israel, Palestinians are not allowed to use the ground water. So Israel control, the whole water resources, the ground water in the West Bank, in the occupied territories. Even the Palestinians in Area A which is today under the Palestinian authority, they get the water from the Israeli company, Mekorot. And a tree in a settlement will have more water than a whole Palestinian neighbourhood.

My friend, she’s making a research on the water and I went with her and heard, for example, they give them specific water for Palestinians, just during a specific time during the week.

They don’t even like allow them to make stores, they don’t allow them to build the stores to store the water. So they will get water for one week, for a day in the week and to store it for the rest of the week.

They need to depend the rest of the week on small stores inside their homes. So they need to tank their water for us in Masafer Yatta. We are not allowed to have any kind of water connection, but the Israeli illegal outpost inside the firing zone are totally connected. And the settlements that are approved by the Israeli government have a 24/7 connection to water.

There is a village that has a master plan. It has a water. So it gets water, and sometimes people from nearby villages try to connect with pipes under the ground, from this village to the firing zone villages, it’ll get destroyed by the bulldozers.

So the only thing that the people can do is to dig water systems, to gather the rain water, like you are talking about thousands of people and tens of thousands of animals that need to depend in this small store of water.

So they finish it in less than a quarter of the year. which what we are facing in my village, for example.

The rest of the year, we have to tank the water. So to have tanked the water, for example, 20 meter cube of water costs more than $100 with the driver, but for the settlers, it costs maybe less than a 20 shekels.

Diana:

Thank you so much for that Ali.

Becca:

One quick thing about the water, because I just see a lot of people I asked clarifying questions. Ali spoke really well about the situation, but I just want to clarify that the West Bank has gone on under development since occupation in 1969 through military orders.

The Israeli army that’s functioning in the West Bank takes roll over all of the water of the West Bank, meaning from pretty much the beginning of occupation, if Palestinians want to drill new wells, fix wells to groundwater, anything similar, that basically has to go through the approval of the Israeli army. And this process ends up being quite solidified during the Oslo period in the 1990s.

If you look up here, the brown is Area A, the yellow is Area B and Area C is green. The areas that you see, Jenin, Nablus is an exception, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Hebron, those are all areas that you can’t see on this map, but they’re built on the top of a hill.

You have these major hill, mini mountains. That’s why the area we’re talking about this called the South Hebron Hills. And the green to the east is lower down below. I point that out as being relevant because the majority of the natural resources, land and otherwise, that’s accessible in the West Bank today is an Area C, which means it’s under full Israeli control. And so Palestinians, even if they live in Area A and want to get water have to go through a process of putting in a request and getting a permit from the Israeli army. That’s the level of control in the West Bank.

And the other thing that I wanted to say that Ali talked about and, and just want to drive the point home, is that not just talking about the differences inside the West Bank, but in Israel. I live inside Israel. I live next to Lod. And in Israel we pay about five to seven shekels, which is probably one or one and a half pounds per cube litre of water. So that’s 1000 litres of water. And that includes sewage systems. Whereas in the South Hebron Hills, for any water that can’t be naturally collected. And a lot of the water that ali talked about that’s naturally collected is also either blocked by settler or violence or by the army from being accessible.

And, and so then you have to bring in water and water tanks. And in areas in the South Hebron Hills, in which it’s not in the firing zone, that can easily cost about to 25 shekels per cube litre. So the Palestinian village of Susiya is paying about five times the price as a settlement of Susiya right next door. And in the firing zone, I saw that Jan asked a question about the condition of the roads. Because the conditions of the roads are so poor and it’s illegal, if you don’t live inside the firing zone to enter in there with vehicle, which means a lot of times vehicles are confiscated by the army. And so, because this water is brought in from vehicles that then have to be four by fours and are sometimes confiscated.

That means the price on average for water can be 35 shekels are higher for the same amount of water that right now I’m paying closer to five shekels for. Just to kind of really highlight the level of inequality that we’re talking about for such a natural and important resource.

Diana:

So you mentioned Jan’s question. So I’ll raise it now. Jan asks, can Ali say something about the condition of the roads, and how that affects tanking in the water, getting to and from schools or hospitals and so forth?

Ali:

Living in a firing zone in Area C and without the master plan of our village being approved by the civil administration, anything, not even a medical clinic, not just the road, a medical clinic or a kindergarten, would be demolished by the Israeli civil administration.

So, if you see like the roads among the villages of the firing zone and in the whole area in Area C, they are just dirt roads. The people who try to put some concrete on the road, not paving it. This will be destroyed by the bulldozers.

Last year, the civil administration did this, not for the Master Plan issue, but for the firing zone issue. There is a big bulldozer called D9 in June last year moved from the outpost of Havat Ma’on, which is in the firing zone, as we said, and they open a road that leads between the outpost of Havat Ma’on to the Palestinians villages and the settlers are using it to drive, to harass the Palestinian shepherds in those village. While the bulldozer was driving from there, it opened the road, the dirt road that had fixed the, the dirt road that lead to the outpost. There was like 100 meter of road that was built for Palestinians in concrete. And it totally smashed it.

This is the situation of the road for the Palestinians. Actually sometimes for emergencies, the Palestinians have to deal with this road. I have witnessed just one month ago, a village that is called Asfy nearby my village of Tuba. They were driving very fast on this dirt road because one kid was in an emergency situation. And he needed to go to the doctor and because of the driver was very worried. He was driving on this road. Two tyres of his car were flat tyres. And we jumped to help him. And we drove very fast and our car also got broken and kid arrived at hospital dead.

It takes it even more time for the woman that also need to give birth. She find herself that she needs to give birth. She had to deal also with the same situation. In in the whole areas of the firing zone, there is no like any hospital or medical clinics. We have to drive through the dirt roads in the firing zone until we reach the city of Yatta.

Havat Ma’on is located on the east part between the rest of the West Bank where we Palestinians can go. Havat Ma’on is blocking our road. And from the other part is the, is the Green Line, it’s Israel, where we, as Palestinians, are not allowed to. So we are blocked in by a settlement in Massafer Yatta. And from the other side, it is the Israel.

Havat Ma’on, it was like immediately established on a road that connects it in just two kilometers and half to the city. But since Havat Ma’on was established, it blocked the road. And the Palestinians until today, since 2000, until today are not able to use this road anymore as a result of the settler violence, because they are last time, my uncle drove there, they smashed his tractor.

For the people now, today, for all their needs, they have to go to Tuba. For example, they have to drive an extra 20 kilometers in order to make detour around this settlement chain to get to the other side of it, to get to the city, to reach the hospital and to get their food and their livestock food.

For the kids, I did the 12 years of school under the military escort. We don’t have a school in our village, so we have to attend the nearest school. Before 2000, for my uncles and for my older cousins, it was easy walking in the morning at seven for 20 minutes, two kilometers and a half, and reaching the school.

In 2002, when the settlers started regularly attacking the kids. And then from 2002 until 2004, the kids have to make this detour of extra walking for more than 10 kilometers on the other side of the outpost in order to reach the other side of it, where the school is.

So you need the whole day, actually from sunrise until sunset, going and coming back to school. In 2004, American volunteers decided to accompany the kids back on these two kilometers road, and then immediately masked settlers with the chains attacked the kids and the volunteers. For Israel, this is an illegal outpost. Instead of opening an investigation against the criminals that attacked six year old kids going to school, or to remove this illegal structure, they allocate a jeep of army to accompany the kids in the morning and the afternoon going and coming back from school.

I have wrote my experience in Haaretz (link above). My cousins who were not born yet in 2004, they are almost getting graduated from high school. They will graduate from high school doing it all under military escorts and Israel will not find a real solution or to face the real problem of the most violent settlers’ existence in Havat Ma’on.

Diana:

I first of all, would like to thank both of you for speaking before I take the last question, because both of you are in such difficult positions and so brave for speaking out from your different perspectives and backgrounds to come together on such an issue, it’s amazing to see, it’s heartwarming to see that. And for both of you to be so eloquent and to take time out to speak to us all about these conditions that are absolutely unimaginable for most of us who are living in the UK, the US and so forth. So I like to try to end on a hopeful note.

What can we do here? As you know, most of us are based in the UK, we’ve got some Americans, some Canadians, some Europeans and so forth, but most of us are outside of Israel/Palestine. What can we do to help? And is there any cause for hope, so that’s a combination of questions from Matan who you saw earlier and from Gillian Moseley, who is the amazing director who produced The Tinderbox, which we screened a good few months ago now.

Becca:

Maybe I’ll start and then Ali, you can have the last word as of course you deserve. I do think that there are reasons to hope. I can’t deny, I wasn’t personally inside the court case on March 15th, but I think there’s an inherently flawed system where the people are sitting in a court case, and many of them didn’t understand what was going on. We’re talking about people whose first language whose mother tongue is Arabic, many of whom don’t speak Hebrew, listening to a court case in a language they don’t understand, decide their fates.

With that being said, I do think there is reason to hope and it’s not by chance that we are trying to do as many webinars like this as possible. I would say that a year and a half ago, or two years ago, really, no one heard about 918. Even Israeli politicians, hadn’t heard about 918 and there was a really thoughtful decision amongst the residents of Massafer Yatta and Israeli and international activists and groups like us, that 918 is something that everyone needs to know about because once everyone knows about 918, it’s actually a pretty clear case of injustice. There’s not nearly as much complexity here that people can try and argue.

And I think you see that also in the state’s arguments. The state isn’t really making some argument that they have nowhere else to practice. I saw some people writing in the comments, what can I do? My member of parliaments pretty deaf, or international pressure doesn’t really do anything. And I understand that feeling, but I do beg to disagree. We’ve seen a lot of situations during the occupation, as part of the occupation, especially inside the West Bank, of full villages, who according to the Israeli high courts could have been destroyed, demolished, moved. And that hasn’t happened because of international pressure and because of Israeli internal pressure.

And I think that that’s an ecosystem that we should be striving for. Me and Ali are here to today. There’s a lot more residents also from within Massafer Yatta and the whole South Hebron Hills and Israeli activists and international activists who are working on this together. Specifically Massafer Yatta, there have been campaigns to save Massafer Yatta.

But I can say, I remember waking up and walking around Tel Aviv one day to graffiti that said Save Massafer Yatta, and photos from residents from within Massafer Yatta, from the youngest of children to the oldest of grandmothers. And that has done a lot to raise the awareness.

The residents inside Alta don’t have the hope of giving up. And that should be our call for solidarity at every moment possible. And to remember there are other cases that are very similar in which both internal and international pressure works. And it’s absolutely our place to make that known.

For those who feel comfortable doing so to politicians, do so to politicians. For those who don’t and are graffiti artists go crazy. I’m not here to suggest which specific thing to do, but I would say that anything that raises awareness first and foremost about 918 is crucial because it’s very hard to campaign against something that people aren’t aware of.

And directed campaigns towards politicians work way better than we tend to think do. It’s not a huge campaign. I understand the problem in a huge campaign of saying end the occupation, which of course for Breaking the Silence, is the ultimate goal.

But on a specific campaign about a specific issue, that’s the type of stuff where politics actually work very, very well, as do public awareness campaigns.

Diana:

Sometimes they like to have a specific task to work focus on. Ali, can we give you the final word?

Ali:

Yes, of course. And I will add my voice to what Becca just said. Raising awareness is the most important thing, because what we are explaining and the policies that Becca and I were telling you about today is that Israel is easily ethnic cleansing 1,300 people.

As I told my experience of my family when an evacuation happened, similar to this happened in 1999. People just were thrown in the Hills, like without any life element. So we are talking about an ethnic cleansing.

And for those like who care about animals, tens of thousands of sheep and goats, dogs also lost their livelihood from where they graze and from where they have a shelter to protect them from the warmth of the summer and the freezing winter.

So raising awareness around the 918, the Massafer Yatta firing zone. Raising awareness around that is very important, and to make the international pressure, because the lawyer told me just two days ago that now it seems that, they are going to make the ruling and it could be for the favour of the army against 1,300 people.

So 1,300 people have to lose their homes for the favour of the army. We don’t have much we can do unless there is international pressure on Israel.

So we invited a few days ago in cooperation with the Breaking the Silence, B’Tsalem and all other organisations that work in the area, European diplomats to come here to the area, to attend the court hearing in order to make pressure.

So you as residents, for sure you have much more power than me for your elected the officials and diplomats here in the country to make a pressure on the Israeli army and governments in order to stop the ethnic cleansing and the forced displacement against hundreds of people.

Thank you so much for everyone that show up to listen to our stories and to know about ma

Diana:

Thank you so much. Please do share this recording, which will go up on the website. Please do tell everyone, you know about what you heard today.

I would like to thank you all for coming along as well. And thank you so much, Becca and Ali.

We had a comment from Swee Ang who’s one of the founders of MAP, Medical Aid for Palestinians, and her comment sums it up nicely. So I’m going to read it out. She says, “special thanks to your two wonderful speakers today. Eye opening, and we must work on this.”

I feel like we’ve all come away with that sentiment. So thank you again so much.