Sami Saada was expelled from his apartment in Haifa and in an attempt to reclaim the property sent letters to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. The letters went unanswered, but found their way into a new book.

By Sheren Falah Saab, published in Haaretz on 10 Aug 2022.

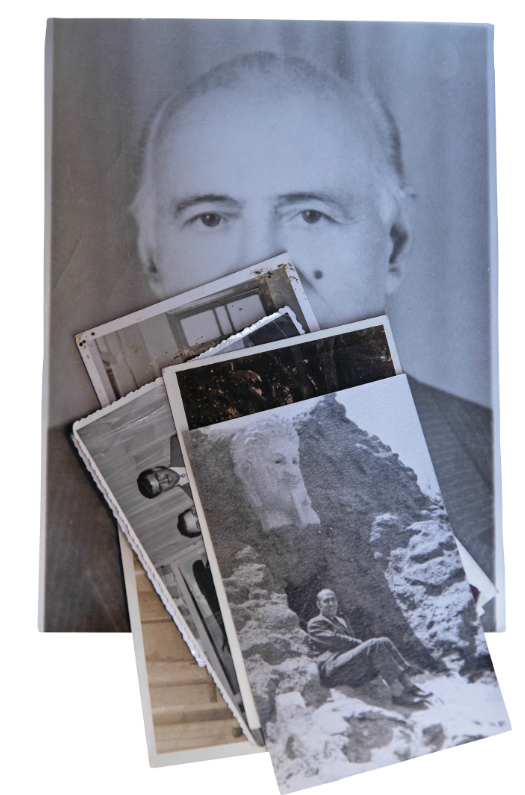

Credit: Reproduction of photos from a family album

On July 11, 1948, nearly two months after Israel’s independence, a group from Israel’s pre-independence Hagana underground appeared at Sami Saada’s apartment door on Mar Elias Street in Haifa’s Lower City and ordered him to immediately move to an apartment on Abbas Street. This followed an order from Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, after Israeli forces captured the city, to concentrate all the Palestinians remaining in the city in the Wadi Nisnas neighborhood and nearby Abbas Street.

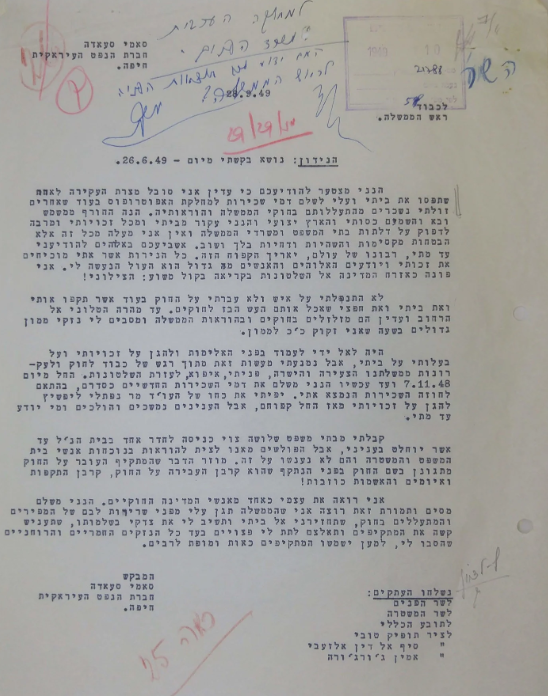

It’s unclear what Saada went through in the first year of Israel’s existence. Like the 3,500 other residents who remained in the city, he probably felt fear and uncertainty as a stranger in his own land – without any political leadership to represent him. But on June 26, 1949, he sent a letter to Ben-Gurion in which he described how he had been painfully uprooted from his home.

‘On July 11, 1948, the military authorities appeared and transferred me to 29 Abbas Street and permitted me to live on the top floor, which is reached by climbing 84 stairs.’

“I, the undersigned Sami Saada, a clerk at the Iraqi Oil Company in Haifa, had been living in recent years in an apartment at 124 Mar Elias Street that contained four large rooms, a kitchen, a bathroom and three balconies. In this apartment, my family and my son found every necessary comfort,” he wrote.

“On July 11, 1948, the military authorities appeared and transferred me to 29 Abbas Street and permitted me to live on the top floor, which is reached by climbing 84 stairs. I obeyed the military order most willingly, despite the numerous hardships that it presented me and my family, and I have in my possession an official license from the military that gives me the right to live at the aforementioned apartment at No. 29, which contains four rooms, a kitchen and a bathroom.”

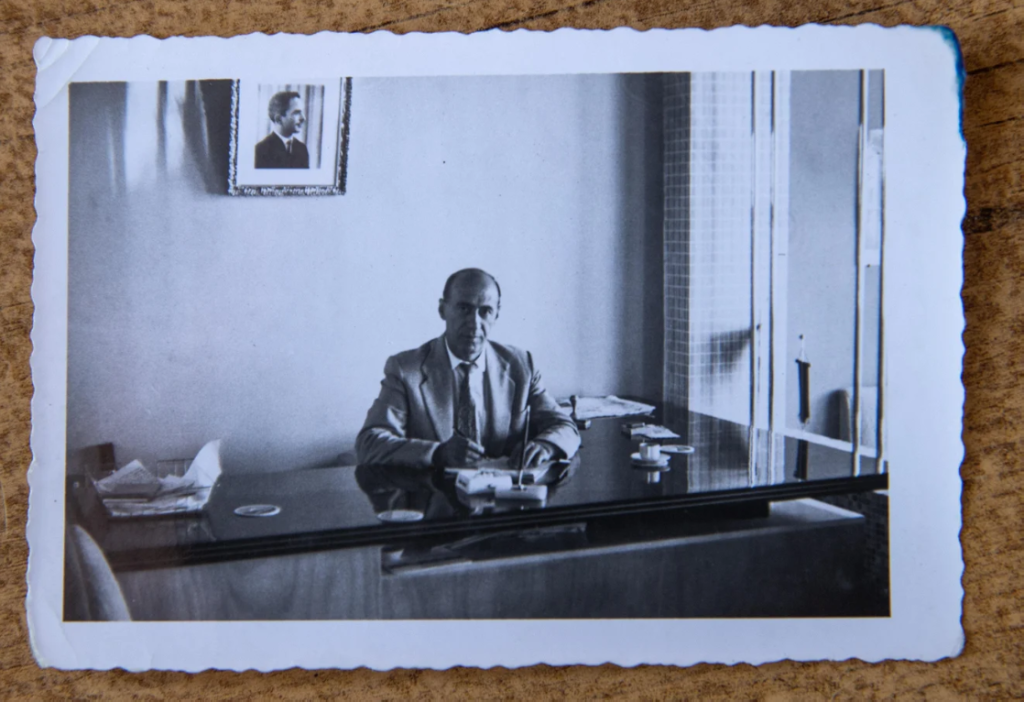

Credit: Reproduction

Until Israel captured the city, Saada, who was born in 1910, shared the apartment on Mar Elias Street with his mother, his wife and his four children. At some point before the battles of the War of Independence reached Haifa in April 1948, the other family members left the city and moved to Lebanon. According to the new country’s laws, the relatives were declared absentees and their property was nationalized.

The appearance of the uninvited Jewish guests at his apartment, as Saada describes it in his letter to Ben-Gurion, was only one of a series of raids by soldiers and their families on homes of local Palestinians, including some who had not fled and remained in Haifa. Such incidents continued to occur for a number of months after the city was captured. And at his new apartment on Abbas Street, Saada also found no peace.

‘At the house, I found a family of strangers composed of a man named Maman, his wife and his brother-in-law. They entered the house after opening it through their special means and took over one room after they emptied it of all the furniture.’

“On January 19, 1949, I returned home at 10 at night after spending the evening with acquaintances,” he recounted in his letter.

“At the house, I found a family of strangers composed of a man named Maman, his wife and his brother-in-law. They entered the house after opening it through their special means and took over one room after they emptied it of all the furniture. An argument between me and them immediately ensued that lasted until midnight and ended with the full understanding that they would leave the house early in the morning, and I therefore declined to call the police. I treated them nicely, particularly since they promised not to remain in the apartment at all.”

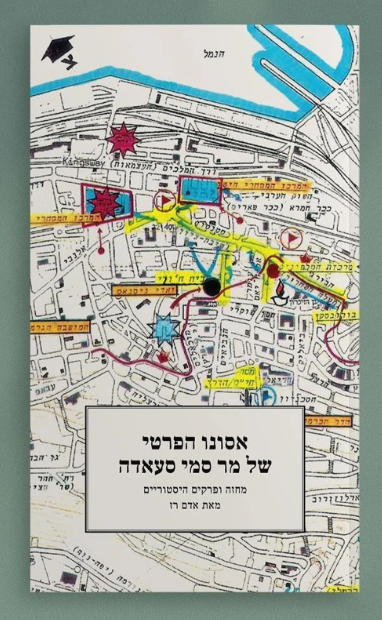

Credit: Current Studio

It doesn’t seem, however, that the guests kept their part of the bargain. Saada went on to write that he went to the offices of the Custodian of Absentee Property to complete the lease on his new apartment only to find that his visitor, a man by the name of Edward Maman, had gotten there first to lease one of the rooms.

“When I went up to go in, I found that Mr. Maman had gotten there before me, accompanied by an army officer who was there to protect him. After they sat with the director for 20 minutes, I was called in. And I had with me one of the clerks from the Iraqi Oil Company, Max Salomon, who spoke on my behalf because I don’t know how to speak the Hebrew language,” Saadi wrote.

“After a few minutes, Mr. Max Salomon explained the following to me in English: The Custodian Department promises and pledges to give me a rental contract for the entire floor. It pledges that Mr. Maman would only vacate the house when my family returns to Haifa, that he would live with his family in only one room, that he would be considered a guest in my home and that he agreed to the special conditions in exchange for a promise from me to accept him in one room.”

“In the months after Mr. Maman took over one of the rooms of my home, his father and mother arrived in Haifa and lived together with him in that room,” Saadi recounted. “While I had hoped that Mr. Maman would keep his promise to me, matters became complicated and the father harassed me at every opportunity and demanded that the house be expanded at my expense.”

But Saada’s story didn’t end with the dispute with the Maman family. In the letter, he went on to describe the invasion of the apartment by another Jewish family that this time resulted in his own eviction from the house.

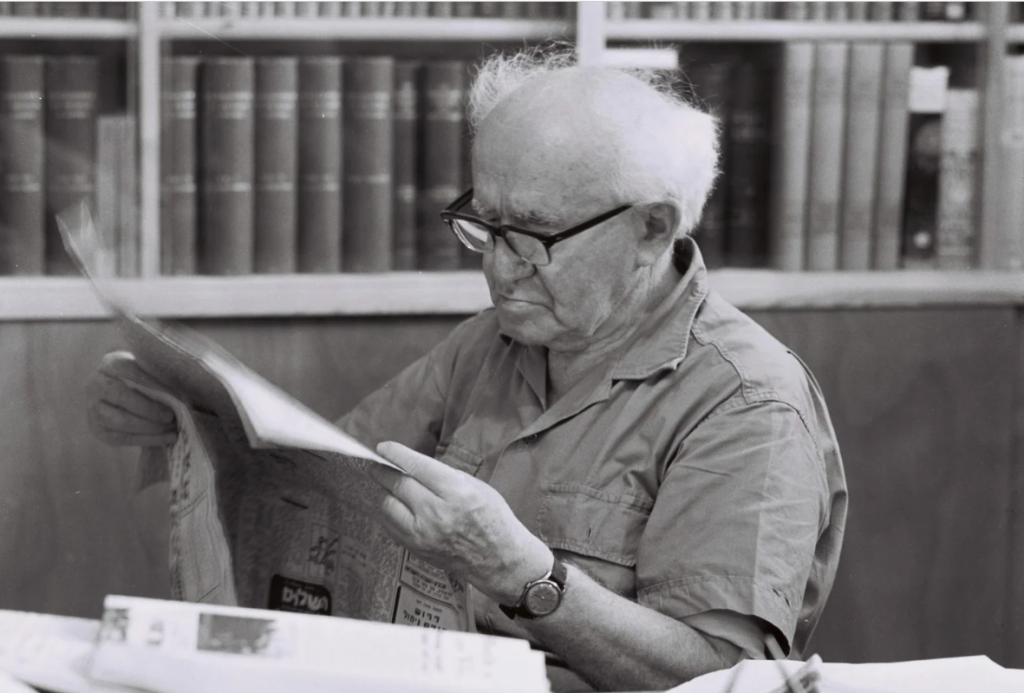

Credit: Fritz Cohen / GPO

“On the morning of April 7, 1949, a military company raided the Arab homes on Abbas Street and after seizing them, threw the tenants out into the street,” he wrote. “Now Mr. Maman and his father have found ample support for their actions against me. Through the military, the military police and the civilian police, they summoned an officer with the rank of captain named Chechik to raid my apartment. He beat me and expelled me from the house. I approached the authorities, but they did nothing for me. The occupiers threw me out and loaded all my furniture into one room.”

Sami Saada effectively became homeless. “I have the rental contract and make the payments in full just as I have made my payments for the residence while others improperly benefit from them, contrary to the law,” he noted.

In addition to evicting Saadi, he wrote that the two families, the Mamans and Chechiks, changed the lock on the front door and prevented him from having access to his remaining belongings there.

The contents of the letters that Saada sent to Ben-Gurion appear in historian Adam Raz’s Hebrew-language book the title of which translates as “Mr. Sami Saada’s Personal Catastrophe” (Carmel Press, Jerusalem). Raz, who is on the staff of the Akevot Institute, which describes itself as an institute for Israeli-Palestian conflict research, found Saada’s letters in Israel’s State Archives and in the Israeli army archives. They shed light on the tragedy experienced by many thousands of Palestinians when Israel was established.

“The Palestinians who remained in Israel were entirely without a voice,” Raz said. “They had remained in the country that had now become Israel and they were seventh-class citizens in it. Not only that. The entire Palestinian social and political structure had fallen to pieces. They were refugees in their land and in their home, subject to Jewish rule, which explains the despair in Saada’s letters.”

Credit: Tomer Applebaum

This is Raz’s second book on the subject, following “Looting of Arab Property in the War of Independence” (Carmel Press), which came out a few years ago in Hebrew.

“In that book, I described broad trends and policies, but in the book about Saada, I wanted to show a more personal side,” he said. “There’s a difference between writing a general statement that they looted Haifa and describing the story from the inside – the fears, the uncertainties, the hardships. It’s the difference between statistics and an individual case.”

And that’s not the only difference. The new book is written like a play, with the addition of two historical chapters.

“All along the way, it was clear that Saada’s story wasn’t suited to an article or a history book because there are too many holes in the plot,” Raz explained. “What was life like at Saada’s house after the two Jewish families moved in? Did he make himself coffee or was he afraid to do that? Who cleaned the kitchen? Did he share the refrigerator with them? There are so many questions, but I didn’t have the answers to them.”

Although he was unable to obtain all of the letters in which Saada described his difficult personal situation, Raz said he was able to gather enough material from the archives to provide an unusually detailed description of what had happened to him.

Credit: Reproduction of a photo from a family album

“His attempts to [pursue] court cases, once he decided to sue the squatters in two different courts, didn’t lead anywhere. The cases are no longer in the archives. Ben-Gurion didn’t respond to the letters that he was sent, but the minorities minister, Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, the Jewish minister who did the most for the Palestinians at the time and opposed Ben-Gurion’s expulsion policy, tried to help him. In the end, it wasn’t successful.”

What prompted Sami Saada to write letters to Ben-Gurion? Did he believe the prime minister would be sympathetic to his plight?

“Despite the Nakba [the flight and expulsion of Palestinians upon Israel’s creation] that occurred among the Palestinian people and the profound institutional change, there are social and political structures that continued to exist within Palestinian society, including the practice of addressing requests to the establishment through letters,” said Dr. Leena Dallasheh, a historian from Humboldt University in California who has also studied documents from Israel’s National Archives.

Credit: State Archives

“In 1926, the British authorities granted citizenship to Palestinians in Palestine and even though they were aware of the limitations of colonial citizenship, they habitually wrote to the British establishment to demand their rights as citizens. Therefore, writing to the Israeli establishment is a continuation of the period that preceded the state’s founding.”

The letters that Saada sent to Ben-Gurion are a window onto the personal suffering of the Palestinians and their dealings with the Jewish establishment that was now in control. In his book, Raz describes the legal battle that Saada tried to wage against the Israeli authorities to obtain the justice he thought he deserved.

On July 13, 1949, he filed a civil suit against Maman and Chechik for squatting in his apartment. The hearing on the case was scheduled for January of the following year. While awaiting his court date, Saada continued sending letters to Ben-Gurion – which, as noted, all went unanswered – and he remained displaced from the apartment.

“Swear to God, you have to let me know how long this oppression will go on,” he wrote on September 28, 1949. “All the papers that I have prove my rights. I beseech the authorities as a citizen of the country: Save me! I didn’t assault anyone and I didn’t break the law. They quickly threw me out into the street and they still disregard the laws and the government’s orders and are causing me major monetary damage at a time when I am in need every bit of funding.”

In another letter, from November 16, 1949, he described his desperate attempts to return to the apartment on Abbas Street and the ordeal to which he was subjected.

“In accordance with your latest instructions, I contacted Mr. Moshe Yatah, the clerk in charge of Arab affairs in Haifa. He told me that he already wrote to you about my case and that he was awaiting your instructions. I would like to take this opportunity to note once again the magnitude of the dispossession and damage done to me and my property by the barbaric acts committed by this group that belittles the law and your orders.”

According to the material that Raz found, Moshe Yatah, who worked at the Minorities Ministry branch in Haifa, did deal with Saada’s inquiry but apparently to no avail.

Credit: Taken from a Family album

“Sami Saada has a lease on the apartment. He continues to pay the rent for the apartment that he cannot live in. The two squatters continue to live in the apartment without paying rent,” Yatah wrote to his superiors.

It isn’t known if Yatah’s efforts helped at all. All signs indicate that Saada never regained possession of his apartment. The archives also didn’t provide answers to many other questions, including whether Saada won his civil suit and whether he in fact lived as a homeless person, as he stated in his letters.

Dallasheh said confiscation of Palestinian property was a deliberate act that was meant to send a message.

“The Israeli establishment transferred the Palestinian inhabitants of Haifa to the Wadi Nisnas area against their will, and they became absentees in the sense that they lost the connection to their property. He and the other Palestinians who did not flee saw how the social, economic and cultural structures they knew had crumbled, but despite the Nakba that they went through, they decided to stay and survive there despite it all. It’s important to remember that the state was in the process of being founded, and there was no expectation that a large number of Palestinians would remain. The priority that was given then to the appropriation of ‘absentee’ properties for the state and the Jewish majority played a role in the process of the state’s emergence and founding,” she said.

Two blows

Ra’id Saada, 60, who lives in East Jerusalem, said he first found out about the letters that his father wrote to Ben-Gurion from Raz, who showed him the material. “What my father told me is that he lived in a house in Haifa and he was moved to Abbas Street. He didn’t tell me what went on inside the house. He didn’t tell me about the letters, and I didn’t know what his life in Haifa was like after the war,” the son said.

“You have to understand that my father suffered two blows. The first was the conquest of Haifa and the second, which was just as painful, was that his family split apart when his wife and children stayed in Lebanon. Through all the years, he longed to reunite the family. It was constantly on his mind. A lot of Palestinian families came apart as a result of what happened in 1948. My father had to make fateful decisions in the shadow of the changes that were forced upon him and that caused confusion within the family as well.”

As if the loss of his home and the longing for his family weren’t enough, the oil company where Saada worked shut down following the war.

Credit: Reproduction from a family album

“His status changed and he lost what he had,” Ra’id said, adding that in the early 1950s, his father tried unsuccessfully to reunite the family.

“Because of various disputes and personal issues, my father wasn’t able to unite the family and he didn’t adjust in Lebanon. He didn’t find his place there. In the end, he separated from his wife, who remained in Lebanon with the children, and after awhile they obtained Lebanese passports.”

From Lebanon, Saada moved to Jordan and found work at the local branch of the oil company where he had worked in Haifa. “I have a suitcase with pictures of my father from when he worked in Jordan. There are even pictures of him with King Hussein,” his son said.

In 1960, Sami Saada married a Palestinian woman named Julia from Beit Jala in the West Bank who worked as a seamstress. He had met her in Amman. The couple had four children, including Ra’id. This new chapter in the life of the family also prompted other changes. Ra’id Saada said in the early 1960s, his father bought a hotel in East Jerusalem, the Jerusalem Hotel, and moved to the city.

“He happened to see an ad in the newspaper about a hotel for sale in Jerusalem,” the son said. “He showed the ad to my mother and she encouraged him to buy it. But he didn’t have enough money so he contacted my uncle, who was working in Iraq then, and they agreed to buy the hotel together.”

The Jerusalem Hotel is still owned by the Saada family. Ra’id Saada runs it with his brother and cousin.

The letters that Sami Saada sent to Ben-Gurion are polite and respectful. His son describes the father as a person who had exceptional patience and took great care with his appearance.

“He always wore a three-piece suit. Even when we went to the beach, he dressed formally. Everyone who knew Sami Saada remembers how much he was respected. People came to him for advice, and he would listen with understanding and find the solutions to every problem. He also was totally fluent in English. When I was studying English in school, I didn’t need a dictionary, because I had my father. He helped me with every question. He loved to write and was a good writer and wrote letters to people his whole life.”

Credit: Reproduction from a family album

It’s unclear why Saada never told his children about what happened at the apartment on Abbas Street or about the letters to Ben-Gurion.

“My father wasn’t a person who talked about his feelings or about things that were bothering him. He kept things to himself,” Ra’id said. “Maybe he did tell my mother about what happened at the apartment in Haifa. I never knew how he really felt.”

At one point, Saada’s eldest son, 78-year-old Rafiq, who lives in Greece, wanted to know what happened to the house where the family had lived. His father agreed to go to Haifa with Rafiq, and Ra’id came along as well.

“It was a few years after the ’67 war. They gave me a camera so I could take pictures of the house, but I did something wrong and I burned the film,” he recalled. “We didn’t find the house either, and my father didn’t say much after the trip.”

In the early 1980s, Sami Saada became ill with Parkinson’s disease. He died seven years later, at the age of 76. His wife Julia died just this past year.

“I think my father died with feelings of anger,” Ra’id remarked, “because right around that time, one of my sisters was killed in the civil war in Lebanon. [My father’s] illness got worse over time and the medications he took led to kidney failure, which led to his death. In the last part of his life, he forgot a lot.”

“My father had a hard life after the Nakba. He wasn’t able to hold onto his family or his home, but that didn’t stop him from moving forward and maintaining the family togetherness as much as was possible. And he did so thanks to his pleasant and intelligent personality,” the son said.

After his father’s death, the son returned to Haifa and this time was able to find the house on Abbas Street. “My father lived there for a long time and seeing the house was very meaningful for me,” Ra’id says. “This house is part of my family heritage, part of my identity.”