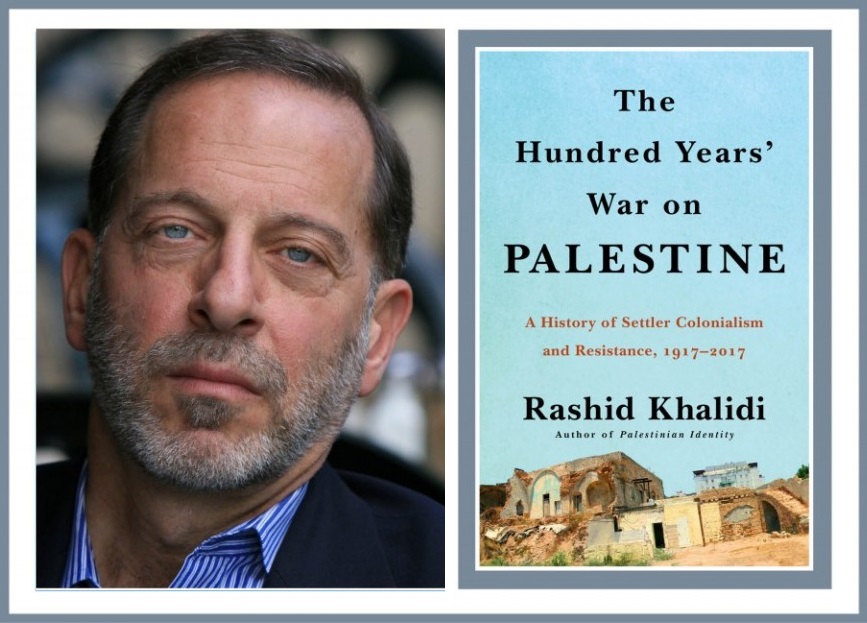

By Rashid Khalidi Profile Books £25.00

Book review Review by Tim Llewellyn

In the midst of Jerusalem’s Old City, on the cusp of the Muslim and Jewish quarters, reposes the Khalidi family library, an archive of scriptures, literature and letters in Arabic, Hebrew and European languages reaching back to the 11th Century. In the early 1990s, Rashid Khalidi found a letter from his great-great-great uncle, Yusuf Diya, a scholar, linguist and Ottoman official, written to the founder of modern political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, in 1899, the year the library was founded. Replying to Herzl’s advocacy of Palestine as the refuge and homeland for the Jews, Yusuf Diya wrote that “the brutal forces of circumstances had to be taken into account…Palestine…is inhabited by others.” Herzl’s reply brushed the Palestinian off, as became the way of the Zionists and their allies and enablers, the empire-builders in London and, much later, Washington. The Arabs, though 90 per cent of the Palestinian population at that time, were not to be taken seriously.

The Khalidis—Rashid, the author, is now Edward Said Professor of Modern Arab Studies at Columbia University—are an old and distinguished extended family of intellectuals, political activists and writers, including Walid Khalidi, Rashid’s cousin, the prime chronicler of the Nakba. This was the Palestinian Catastrophe, of 1947-49, when Palestine was purged of nearly 60 per cent of its Arab population by Jewish fighters and terrorists, later the Israeli army. Rashid Khalidi has written seven books on Middle East politics, the U.S. involvement there and the Palestinians, and is co-editor of the authoritative Journal of Palestine Studies.

One of the many merits of the book under review is the way Khalidi uses his family and his own life experience to tell this tragic, yet-to-be-righted, story of the Palestinians. For example: his father, Ismail, took from his elder brother, Husayn, Mayor of Jerusalem, the news of the Palestinians’ collective rejection of partition to King Abdullah of Jordan, in November 1947. The King was in favour of the separate states plan as he sought “wisaya” or “guardianship” of the promised Arab sectors. “You deserve what happens to you,” Abdullah angrily told Ismail. That Jordanian tutelage duly came anyway, in the next year, after the Nakba, for the West Bank and the Khalidis’ home of East Jerusalem. West Jerusalem, home of thousands of Arabs before 1948, had fallen exclusively into the hands of the Jewish forces.

Much worse was to follow, and still obtains, though not because of any lack of Palestinian resistance, as Khalidi makes clear at each step of his six selected stages of the wars against Palestine; but because of the massive weight of international “interests” that were thrown against the Arabs and used to support the Zionists from the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the British enabling of Jewish statehood during the mandate years, to the creation of Israel in 1948, the war of 1967, the war on the PLO in Lebanon in 1982, the betrayals of Oslo, and now the Trump “deal of the Century”, which enshrines a Jewish Jerusalem and stamps the Occupation (and therefore an apartheid-style rule) with American superpower authority.

Khalidi the author is uniquely well placed to recount this story, and suggest the makings of a solution. He was born and brought up in New York City, but studied and lived in Beirut in the crucial PLO years of the seventies and early eighties, often working with the movement. He and his wife and children were there when Israel invaded, besieged and battered Lebanon from air, land and sea during three months of the summer of 1982. He was there during the Sabra-Chatila Palestinian refugee camp massacre in September, when Israel’s forces surrounded the camp and gave the Lebanese Christian forces’ killers access to the helpless civilians*. He thus sees both through the Palestinian lens and that from outside, especially from the commanding heights of the United States.

He reminds us of the British responsibility for it all, from the Balfour Declaration onwards, including the vital incorporation of that template into the League of Nations mandate for the British rule of Palestine, supposedly and ostensibly to bring the Palestinians to self-government.

He reminds us too of British deviousness, hence Arthur Balfour, British Foreign Secretary, in a confidential memorandum to the Cabinet, in 1919 (not to be published until well after Israel was a fact more than 30 years later): “…in Palestine we do not propose to go through the form of consulting the present inhabitants of the country…the four Great Powers [Britain, France, the U.S.and Italy] are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions…of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land,” (My emphasis.)

So much for the self-determination aims and principles of Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations. But as Khalidi later stresses, since the United States took over the role of Imperium, and main sustenance, propagator and protector of Israel and its aggressive settler-colonialism, it has—even at its occasional moments of apparent support for a just solution, say under the first President Bush or Barack Obama—never stepped away from its own strategic interests, which it has seen as protecting and projecting Israel as a central strut of U.S. foreign policy. The European powers, Britain and France, having done so much to support Israel in the 1950s and early 1960s, with political and military support, and France’s vital contribution to Israel’s nuclear weapons programme, have continued on course since Washington seized the reins in the mid-1960s. They have followed lamely in the U.S. wake. The Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia have done nothing effectively to challenge the U.S.

President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital “summarily disposed”, says Khalidi, of “the centre of the Palestinians’ history, identity, culture, and worship…without even the pretence of consulting their wishes,” a decision he sees in the direct line and thinking of the Imperialist Balfour.

Khalidi however does not acknowledge a clear Zionist victory. While Zionism did create a thriving new people in Palestine, it could not supplant the country’s original population. He thinks it unlikely it will or could. For all its might, “the Jewish state is at least as contested globally as it was at any time in the past.” But though the Palestinian cause has made good progress internationally, even among (younger and even Jewish) Americans, it has never seized hearts and minds as effectively as Israel did from the start, with its massive advantages of superpower backing and, later, the impact of the Holocaust and Zionist political power which that tragedy massively increased, most importantly in Europe and the West.

So, how to fight this? Khalidi , like many of his eminent Palestinian compatriots these days, emphasizes the issue of inequality: “equality of rights is key to a just, lasting resolution of the entire problem.”

The population of former Mandate Palestine divides almost equally between Jews and Arabs. Five million Palestinians in the Occupied Territory of the West Bank, Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip have no rights at all. The 20 per cent of Israelis who are Palestinian, living within Israel, lack full citizenship and national subject status, and even these are being eroded by Israeli Government fiat. “That inequality is the central moral question posed by Zionism, and that it goes to the root of the legitimacy of the entire enterprise is a view shared by some distinguished Israelis,” Khalidi writes.

Any resolution of the conflict will fail if it is not based on the principle of “equality of human, personal, civil, political, and national rights…” whatever structural formula, one-state, two-state, is ultimately agreed. This, he argues, is the way to reach those elements of potential Western support that the Palestinians have yet to tap.

Khalidi has straight talk for the Palestinians on the question of compromises. While his condemnation of Israel’s policies and historic Zionism is as unrelenting as his analysis of the events of the past century in the Holy Land, he says that Palestinians also must recognize that there are now two peoples in Palestine “irrespective of how they came into being, and the conflict cannot be resolved as long as the national existence of each is denied by the other.”

He advocates a massive and unprecedented Palestinian effort to engage American, European, Russian, Indian, Brazilian and Chinese public opinion, skills Palestinians abroad have massively improved in such areas as political activism, literature, drama and cinema, but are still sadly lacking among political leaders in Palestine. The United States should no longer hold the ring on any future negotiations but be treated as “an extension of Israel.” Issues created by the 1948 Nakba, shut down by UN Security Council Resolution 242 after 1967 and Israel’s famous victory, need to be reopened: the return of refugees , the 1947 partition borders, the status of Jerusalem as a corpus separatum and the basic rights of the Palestinians inside Israel.

Khalidi concedes that all this is a long haul given the present dispositions of world power, but these are changing. And one thing that has never changed, which the Khalidi family down the years has exemplified, is sumud—that unique Palestinian determination to stay put, to keep going, to survive in place, whatever the odds.

*It was Rashid who telephoned me at the Commodore Hotel in Beirut on the evening of September 16, 1982, to tell me that “something was going on” at the Sabra-Chatila refugee camp. It was nearly two days before reporters, diplomats and NGO officials were able to get to the camp and discover what had happened. My report on the 1400 GMT September 18 newsreel of the BBC World Service was the first the outside world, and the Israeli Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, knew of the massacre.

Tim Llewellyn is a member of the Executive Committee of the Balfour Project and a former BBC Middle East Correspondent.