Eugene Rogan is Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at Oxford University, where he has taught since 1991, a Fellow of St Antony’s College and Director of the Middle East Centre. He took his B.A. in economics from Columbia, and his M.A. and Ph.D. in Middle Eastern history from Harvard. In 2017 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy. He is author of The Arabs: A History (2009, 2017), named a best book of 2009 by The Economist, The Financial Times, and The Atlantic Monthly. His new book, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East (2015), was named a best book of 2015 by The Economist and The Wall Street Journal. His earlier works include Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire (Cambridge University Press, 1999), for which he received the Albert Hourani Book Award of the Middle East Studies Association of North America and the Fuad Köprülü Prize of the Turkish Studies Association; and The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948 (Cambridge University Press, 2001, second edition 2007, with Avi Shlaim). His works are translated into 18 languages.

Eugene Rogan:

Over a century after Lord Balfour made his declaration, there is little agreement about what Lloyd-George’s foreign secretary or subsequent governments intended to do with Palestine. It should not be such a mystery. Britain wanted Palestine for its own empire, for simple geo-strategic reasons born of the First World War. Towards that end, the British government sought to exploit the Zionist movement. Not to create a Jewish state, but to partner with Zionist settlers in managing Palestine over the predictable opposition of the Palestinian Arab majority. If one were to compare Palestine to the French mandate in Lebanon, the Zionists were the Maronites of British Palestine: a compact minority community that would openly advocate for a British mandate at the Paris Peace Conference and cooperate with the British in governing the territory.

This wish to draw Palestine into the British Empire was entirely new in 1917. Before World War I, Britain had no declared interest in the Ottoman territories of Palestine. This disinterested position would continue well after the outbreak of war. The de Bunsen Committee, convened in April and May 1915 to consider British imperial interests in Ottoman territory in Asia, practically disavowed any claim on Palestine, aside from a rail terminal in Haifa linking Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. “Palestine must be recognised as a country whose destiny must be the subject of special negotiations, in which both belligerents and neutrals are alike interested,” the de Bunsen Committee Report concluded.

These principles guided British partition diplomacy when Sir Mark Sykes concluded an agreement with Charles-Francois Georges Picot between April and October 1916. Palestine was to be internationalised under joint Russian, French and British administration, with Britain securing that enclave in Haifa for its Mediterranean port.

Between October 1916 and November 1917, Britain’s position changed dramatically from one of disinterest to a determination to secure Palestine for its own imperial control. One driver of that change was the Sinai Campaign. In the opening years of the war, the British had defended the Suez Canal from its western banks. With no wells or fresh water supply, troops could not be posted to the Sinai Peninsula. This had allowed the Ottomans free rein in Sinai, and to mount two attacks – in February 1915 and August 1916 – on the Suez Canal Zone. Modern artillery could strike ships in the canal from five or more miles away. From their lines in southern Palestine, with water from perennial wells, a hostile power could threaten shipping transiting the Suez Canal at will.

To drive the Ottomans out of the Sinai Peninsula, the British fought a slow campaign through the remainder of 1916 and into the early months of 1917, laying a railway line for supplies and a pipeline to provide water for the troops and their animals. They faced well entrenched Ottoman forces in Gaza who defended their territory against major British assaults in March and April 1917. The First and Second Battles of Gaza ended in British defeat, which made the British yet more aware of the danger posed by a hostile power in Palestine. It was this wartime experience that changed Britain’s position from one of disinterest to seeking dominion over Palestine.

It wasn’t until the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917 that British forces broke through Ottoman lines in southern Palestine and began their rapid advance towards Jerusalem, which surrendered in December. Three days after the breakthrough at Beersheba, Balfour pledged the British government’s best efforts to establish a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

It is clear that wartime experience had driven Britain’s new interest in securing Palestine for its empire. We can pinpoint that newfound interest to the period between the Sykes-Picot Accord in October 1916 and the Battle of Beersheba in October 1917. Yet in this fast-moving change of imperial policy, there is another element that requires explanation: the decision to back Zionist ambitions in Palestine.

The British government had no interest in Zionism before WWI. In 1913, the FO permanent under secretary, Sir Arthur Nicholson, refused to receive Nahum Sokolow, an executive board member of the World Zionist Organisation. He left his secretary to receive Sokolow, and after the secretary briefed Nicholson on the meeting, he replied: “In any case we had better not intervene to support the Zionist movement. The implantation of Jews is a question of internal administration on which there is great division of opinion in Turkey.” British officials were no more interested in Zionism when Sokolow tried to secure a second appointment in July 1914. “It is not really necessary that anyone’s time should be wasted in this way,” a Foreign Office memo noted, and the second visit never took place.

This is not surprising. Zionism was dismissed as a utopian movement with a very limited following in Britain in 1914. Out of a total British Jewish community of 300,000, there were no more than 8,000 members of Zionist organizations. So there was little reason to ‘waste time’ over a marginal political movement that attracted only an idealistic fringe of the Jewish community. And British society was highly anti-Semitic by today’s standards. One didn’t expect British officials to advocate Jewish movements.

It wasn’t until 1917 that Britain saw a strategic value in Zionism and their interest in the movement began to change. The Russian Revolution in 1917 placed Russian commitment to the Great War effort in question. Many in Britain believed Jews in the provisional government of Alexander Kerensky might encourage the Russian military commitment to the war if they saw an Entente victory advancing Zionist goals in Palestine. Others believed American Jews would influence Woodrow Wilson to enter the War, tipping the balance in the Entente’s favour, for the same reason. America was slow to enter the war – they only declared war on Germany in April 1917 – and its population unenthusiastic about the war effort. A pro-Zionist policy might encourage influential Jews advising the White House to accelerate America’s engagement. As Tom Segev comments, this was Zionism turning anti-Semitic clichés about a Jewish international that controlled global politics and finance to advantage. In the endless total warfare of WWI, Lloyd George and his government were open to any alliance that might help end the war with an Entente victory. And so Lloyd George and his government courted the Zionist movement.

There was another reason for Britain to seek a partnership with Zionism in 1917. Just one year earlier, Mark Sykes had agreed a distribution of Ottoman Arab territory with Georges Picot. France would hardly be sympathetic to new British claims to Palestine after both France and Russia had made clear their own interests in the Holy Lands, and had agreed to a compromise that left Palestine under international control. The British needed a third party to take responsibility for such a dramatic shift in partition diplomacy. By supporting the Zionist movement, Britain could stake its claim to Palestine not in terms of its selfish imperial interests, but as a matter of historic social justice – resolving Europe’s ‘Jewish Question’ through the return of the Jewish people to their biblical homeland. It was in that spirit that Lord Balfour addressed his fateful letter to Lord Rothschild promising British best efforts towards that end. It looked like Britain was promising Palestine to the Zionists when in fact Lloyd George’s government was using the Zionist movement to secure Palestine for themselves.

And so Balfour made his fateful declaration, committing the British government to exerting their “best endeavours” to “facilitate” the “establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”. Note: a ‘national home’, not a state; ‘the Jewish people’, not the Zionists. While many critics have focused on the fact that the Balfour Declaration does not refer to the Palestinians by name, but just to ‘existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’, I think the Balfour Declaration is equally non-committal to Jewish and Arab national identity. The Declaration is all about ‘civil and religious rights’ rather than national rights. The Balfour Declaration, in other words, is not a commitment to the establishment of a Jewish state. I see it rather as the establishment of a compact minority community in Palestine designed to facilitate British rule of a new colonial acquisition. Totally dependent on the British for their position in Palestine, the Zionists would be reliable partners in managing the mandate against the predictable opposition of the Palestinian Arab majority.

Britain was in no doubt of Palestinian opposition to its plans. They had enough operatives on the ground from December 1917 onwards, after Allenby’s occupation of Jerusalem, to have reliable intelligence on the political views of the local population. And if they had bothered to read the report filed by the American King Crane Commission in the summer of 1919, they would have had all the data to conclude their Balfour promise was a non-starter. The King Crane Report noted “that the non-Jewish population of Palestine – nearly nine-tenths of the whole – are emphatically against the entire Zionist program. The tables show that there was no one thing upon which the population of Palestine were more agreed than upon this.” The report also noted that “no British officer consulted by the Commissioners, believed that the Zionist program could be carried out except by force of arms.’ The British knew how strongly Palestinians opposed their plans.

Paradoxically, faced with such local opposition, the British seem to have been only more convinced of the benefits of establishing a loyal ally through the Zionist settler community. Jewish settlers were Europeans, and so culturally closer to the British than the Palestinian Arabs (though British officials continued to ‘Orientalize’ the Jews and to view them as lower in the social Darwinian scale than the British). A compact Jewish minority, viewed with hostility by the majority population, would be entirely dependent on the British to protect their position. Such dependence made them reliable. The British could trust the Zionist settlers to partner in the management of Palestine because the mandate made Zionist settlement possible and protected the settler community from the hostile natives.

“Dependent and reliable” was the holy grail of empire. The French resorted to minority policies more readily than the British. The Maronites in Mount Lebanon were one such minority community who actively lobbied for a French mandate. The French tried to foster such dependence with the Alawite and Druze communities of Syria, offering them mini-states for self-government under the French mandate in Syria. The British, for their part, had turned to the sons of Sharif Hussein of Mecca in a policy known as the Sharifian solution, placing Hashemite sharifs on the throne of Transjordan and Iraq. Foreigners in their own kingdoms with no popular support base or financial independence, Britain could be confident that Amir Abdullah in Trans-Jordan and King Faisal in Iraq would be dependent and thus reliable partners in running those states. Britain had no Sharifan solution for Palestine. Instead, the Zionist settler community fulfilled that role.

However, the Zionists would only be dependent and reliable so long as they remained a minority. Were they to achieve majority in Palestine, they would sue for independence. Britain had no doubt of the nationalist nature of the Zionist movement. It was as much to remind the Yishuv of the limits of Britain’s commitment as it was to calm Palestinian Arab antagonism that Winston Churchill issued his 1922 White Paper. Famously, Churchill ruled out a Palestine “as Jewish as England is English.” He ruled out “the disappearance or the subordination of the Arabic population, language or culture in Palestine”. He stressed that the terms of the Balfour Declaration “do not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded in Palestine.” What Churchill was saying was that the Jewish community of Palestine should remain a compact minority community, and within those limits they could look to Britain to advance the Jewish National Home project.

Of course, the British never reached an equilibrium point in advancing the Jewish National Home and preserving the peace in Palestine. After a wave of riots in 1929, the British organized a series of inquiries and issued a series of white papers against the background of spiking Jewish immigration following the Nazi seizure of power, between 1931 – 1933, and the passage of the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws in 1935. From an average 5000 immigrants per annum in 1930-31, the numbers rose to 9600 in 1932, 30,000 in 1933, 42,000 in 1934, and peaked at nearly 62,000 in 1935. By 1936, the Yishuv had grown from less than 10 percent to over 30 percent the population of Palestine, with no end in sight. Jewish immigration and land purchase compounded the economic effect of the Great Depression to raise misery and anxiety in the Arab Palestinian population. In 1936, the Palestinians broke out in full revolt against both the British mandate and the Jewish community fostered by the mandate.

The British secured a pause in the first phase of the Arab Revolt to dispatch yet another commission of inquiry. However, when the Peel Commission reported in August 1937, they basically declared the mandate a failure:

“An irrepressible conflict has arisen between two national communities within the narrow bounds of one small country. About 1m Arabs are in strife, open or latent, with some 400,000 Jews. There is no common ground between them. … Their cultural and social life, their ways of thought and conduct, are as incompatible as their national aspirations. These last are the greatest bar to peace.”

In other words, Britain for the first time in 20 years since the Balfour Declaration acknowledged that their mandate had set off a conflict between rival and incompatible nationalisms, Palestinian Arab and Zionist. According to the Peel Commission, this situation could be resolved only by the termination of the mandate and partition of the territory of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, governed by treaty relations with Britain “in accordance with the precedent set in Iraq”. Let that be your first warning signal about how ‘independent’ Britain intended the Jewish and Arab states to be. The 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty preserved British pre-eminence in foreign relations and military affairs in ways that simply re-structured the colonial relationship. A sort of Empire by Treaty.

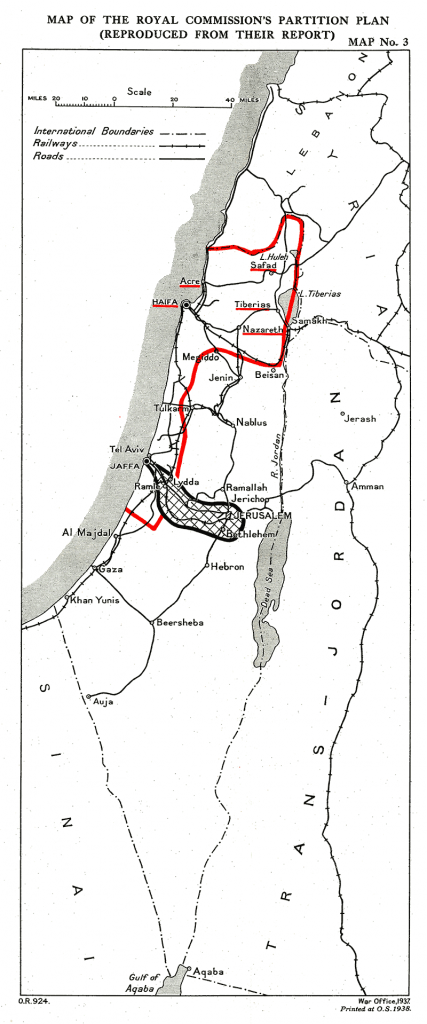

I would argue that the Peel Commission’s recommendations were about re-structuring the colonial relationship in Palestine but not to end it. Start with the 1937 partition map. The Peel Commission allocated roughly one third of Mandate Palestine to the Jewish state, stretching from the Galilee panhandle south to include Safad, Tiberias, and Nazareth, the frontier turning towards the West at Beisan, to take in the coastal plain from Acre and Haifa through Tel Aviv and Jaffa in a sort of inverted L of territory. Two things are obvious when you look at the map: The British had concentrated the key ports and economic centers of Palestine and placed them in the hands of their Zionist partners. More significantly, a country so small would be evermore dependent on British protection against Arab neighbors in Lebanon, Syria and the Palestinian territories whose hostility to the Zionist project was obvious to all. So rather than conceding statehood to the Zionist movement, the British were reorganizing the economic center of gravity in the Palestine mandate and placing that territory under their dependent and reliable Zionist partners.

This reversion to dependent and reliable partners is equally apparent in the Peel Commission’s plans for Arab Palestine. The remaining 2/3 of Palestine was to be united with Trans-Jordan under Amir Abdullah’s rule and the mandate for Trans-Jordan replaced with a Treaty of so called ‘independence’. In other words, the British were at long last applying the Sharifian solution to Palestine, and placing that troubled land under the control of a dependent and reliable ruler – Amir Abdullah.

The Peel Partition Plan of 1937 was not a call for Jewish or Arab independence. It was instead an effort to restructure the colonial relationship, along the tried and tested lines of Iraq, to shut down the dysfunctional mandate and restructure the imperial relationship in an Empire by Treaty scheme.

Needless to say, the Palestinian rejection of the Peel Report resulted in two further years of intense insurgency, forcing the British to deploy 25,000 soldiers and policemen to suppress the Arab Revolt. To restore the peace, the British issued a final White Paper in 1939 that laid partition to rest. The 1939 White Paper called for a limit to Jewish immigration to 15,000 per annum for five years, or a total of 75,000 new immigrants. This would bring the Jewish population of Palestine to 35% of the total. After five years, there would be no further immigration without the consent of the majority, and no one was under any illusions about the majority’s views on the matter. In 1949, Palestine would gain independence (again, presumably the sort of partial independence the British had already conferred on Iraq and now Egypt by 1939) under majority rule.

The telling detail in the 1939 White Paper is the precision with which Britain treated Jewish immigration: 15,000 per year for five years, taking the Jewish population to 35%. Full stop. By this policy, the Yishuv would remain a compact minority forever dependent on British protection in hostile surroundings. Had the British allowed the Jewish community to surpass the 50 percent mark, they almost certainly would face a Jewish nationalist bid to drive the British from Palestine just as they faced from the Palestinian Arab population. As a compact minority, as the Maronites of Palestine, the Yishuv would reinforce Britain’s imperial position in Palestine against the demands of the Arab majority. As a majority, the Yishuv would mount their own bid for independence.

Which is, of course, what happened. The Zionist Executive in Palestine, led by David Ben-Gurion, rejected the 1939 White Paper, but with war against Nazi Germany brewing, Ben-Gurion famously vowed to fight the war against the Nazis as if there were no White Paper, and to fight the White Paper as if there were no war. Other more radical members of the Yishuv openly declared war on Britain, launching a Jewish Revolt that would prove fatal to Britain’s position in Palestine. As the Irgun announced in their declaration of war in January 1944, “There is no longer any armistice between the Jewish people and the British Administration in Eretz Israel. Our people is at war with this regime – war to the end.”

The Jewish Revolt of 1944-47 proved fatal to the British mandate, in which the targeted assassination of officials, the attacks on infrastructure, the bombings of police stations, the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel were milestones. The growing pressure on immigration limits as shiploads of illegal refugees, mostly survivors of the Holocaust, made their way to the coasts of Palestine, as the Yishuv surged towards a critical demographic mass to realize their nationalist aspirations, compounded Britain’s untenable position. But in my view, what condemned the British position in Palestine once and for all was the collapse of Yishuv support for British rule in Palestine. In partnership with a compact Jewish minority, the British could hope to hold Palestine against the nationalist opposition of the country’s Arab majority. Against the rival and incompatible nationalisms their mandate unleased, Britain was left with no choice but to hand the Palestine Mandate over to the United Nations and withdraw.

So to conclude, Britain’s goal in Palestine was always to retain the territory as part of its empire – an empire it imagined would last for generations. The Jewish community in Palestine was an essential partner in securing and retaining Palestine…but only as a compact minority community. Britain never anticipated giving Palestine over to the Yishuv, and their policies supported the Yishuv only within the limits of their usefulness as partners in the imperial project. The fatal mistake the British made was believing they could manage the rival and incompatible nationalisms they set off in Palestine. As the population of the Yishuv reached a critical mass, the British had become irrelevant in Palestine.

Diana Safieh

Thanks so much for that.

So we’ve got a couple of questions already. If you’ve got any questions for Eugene, please pop them in the chat box and I’m going to try to get through as many of them as I can, but I can tell you already, we’ve had a few, so I’m going to try to batch them for ease and to get through as many subjects as possible.

The first one is about religion and how that might have influenced Balfour and Lloyd George. We’ve got this from Phillip Francis: “Balfour was not religious, but Lloyd George was a devout Methodist and a Bible based Baptist when he was at home in Wales. His pastor in Wales emigrated to America and was involved with founding the modern Southern Baptist movement who are fundamentalist Christians in the United States today. It seems to me that there are strong parallels with Lloyd George’s position then and the position of those who support Trump today, and the support of American Christians for the state of Israel. Is this a topic that you have looked at, or have any insight into?”

Then to add to that, Sir Vincent Fean, our chair of the Balfour Project has asked – well, he says, “Thank you Eugene,” and I second that, thank you very much. “What weight do you attach to the individual attitudes of, for example, Balfour and Lloyd George as restitutionists? – and the power of the Old Testament in policy thinking?”

So it’s quite a lot for you.

Eugene:

They’re questions that fit rather nicely together, because there is a certain amount of Bible thumping that goes with the way the British frame their claim. I cannot read the minds or hearts of Lloyd George, or Balfour or others in the cabinet. I know that they are all on record saying things that would set off alarm bells for anti-Semitism by today’s measure and so I always take with a grain of salt, their commitment to do well by the Jewish people. This doesn’t mean that they were openly hostile to the idea of the Jewish settlement movement in Palestine, or that they couldn’t see that there would be something kind of mystical and great about the idea of the restoration of the Jewish people to the biblical Homeland. That might have played to romantic ideals that Balfour was himself quite vulnerable to, but none of it would have happened if it hadn’t advanced the interest of the British empire.

That’s where I think the argument always, in a sense, falls into mistaken territory. I’ve given some of these arguments before and had people just push back saying no, you know, they were really won over by Chaim Weizmann and his invention of acetate and what that did for allowing artillery shells to be constructed in the First World War. He was able to get access and persuade, you know, Balfour and Lloyd George of the great idea.

You know, I’m sure that Chaim Weizmann was very persuasive, but you know, that’s why I quoted at the beginning the way in which Nahum Sokolow – who was himself, a very charming, charismatic spokesperson for the Zionist movement – simply couldn’t get his foot through the door at the Foreign Office up until 1914.

In other words, Zionism really is only worth thumping your Bible in favor of when it’s going to advance the interest of the British empire. I think we can really trace it back to that critical moment between when Sykes – Picot was concluded and when the British break through into Southern Palestine. They suddenly saw that they needed Palestine to secure the Suez Canal as the vital waterway for their empire and having Palestine in World War One and in hostile hands really forced a rethink that was entirely new.

Suddenly, the Zionist movement – never of interest to politicians of Britain before – had a kind of critical interest or importance to it that meant it was arguably in British empirical interest to give it a new, serious, second thought.

As far as how that links to Lloyd George’s pastor, his travels to America and the enthusiasm for Christian Zionism, going back a century ago, I don’t know a great deal beyond what I read in magazines and newspapers about the support of Christian Zionism. I’ve always been rather cautious about how kind that support was to the Jewish people. It always seemed rather instrumental to me that Christian Zionists wanted to bring on the end of time, and at a time which condemns Jews to eternal damnation because they did not accept Jesus’s message. So, you know, in a pragmatic way: allies, perhaps, but not people who made you want to invite them round for a Seder.

What drives Trump was always a mystery to me happily. We don’t talk about it now as much as we used to and his ideas seem to be less influential in the way we talk about things in Palestine. Thank you.

Diana:

The questions are coming in thick and fast. I’m going to read you a question from Magan Singodia and one from Harry Hagopian. Sorry, name pronunciation is not my strong point, as you can tell. Thank you. So from Magan: “If the British had granted the Palestinian independence in 1936 and then in ‘47, have the Palestinians any grounds for claiming to be an independent state?” So obviously very much on the mind after our conference last week about the rule of law. Then from Harry Hagopian: “Many thanks for a wonderful overview of this historical chapter. If I fast-forward yesterday and look at today, with the UK pooh-poohing the ICC investigation and refusing to recognise Palestine as a state under international law, what are the UK’s “mandatory” designs today – if any?”

Eugene:

Oh goodness. It’s such a good question. So UK mandatory designs today. In a sense, I left you at the end of my talk with a Britain that already by 1947 had been reduced to irrelevance and handed over to the United Nations. If they were irrelevant, even while they had troops on the ground in Palestine, imagine how much less relevant they are in an age where Britain’s concerns to try and make good the economic potential that drives this government’s Brexit policies by not doing anything that gets in the way of trade relations. And I’m afraid that when it comes to justice for Palestine, I really do think that Britain’s moral obligations will be sacrificed on the altar of post-Brexit trade. I could be wrong. I wish this country nothing but success as it moves forward and I like my adopted homeland, but on this one policy I’m not overwhelmingly hopeful. So that’s on the second question, now the first one.

I’m not an international lawyer, so I can’t recite for you the legal reasons why the Palestinians would have a claim, but even in terms of the Paris Peace Conference and the King-Crane Commission and their investigations and whatnot, what drove the claim to statehood was self-determination. The imposition of a mandate against the wishes of the majority population was a violation of self-determination. So I think certainly in 1919 and 1920 terms, the legal position of Palestinian claims to independence were stronger than Britain’s right to impose its colonial situation on the Palestinian people against their wishes. But it was still an Imperial age. Britain was an important power in the League of Nations. The United States was not a member of the League of Nations. And, you know, it was more concerned with what the French were going to sanction than really what the rest of the international community, let alone what the Arab people of Palestine would sanction.

I think that the Palestinians have had a legitimate claim to independence right through, but they’ve never had the force to impose that will and they lost it by losing a war in 1947-48, a civil war, and in subsequent Arab-Israeli conflicts in which the Palestinians lost territory by dint of conquest. But I don’t think they’ve ever lost their moral claim to statehood. And it’s been a claim recognized by more countries in the world today than those that have not – shame on Britain for not being one of them.

Diana:

Well, if that is a question that any of our audience are interested in exploring further, we have all the recordings from our conference last week, which touched on these topics extensively and from some amazing experts in the field. So I have posted the link to the recordings in the chat box. We also had a statement come out to conclude the conference that is also available on the website. We’ve also got a really interesting letter from Crispin Blunt MP to the Prime Minister about the ICC. So do check those out on the website. Like I said, all the links are in the chat box.

Right. So another question for you, Eugene. This is from Samir Shawa. “Can you please explain why Lord Balfour couldn’t wait for his army to occupy all of Palestine? Allenby entered Jerusalem five weeks after the ominous declaration, the mandate was given to Britain years later.”

Eugene:

Well, I think that the British government as a whole was looking at a rapidly evolving situation where the forces they were marshaling under Allenby and the Egyptian Expeditionary Force were in a position to break through Ottoman lines. And while it’s true it would take until December before the British entered Jerusalem, it was three days after the British had broken through Ottoman lines and were beginning their advance from Be’er Sheva and Gaza and moving up the coastline towards Jerusalem. So they were looking at a territory that was increasingly coming under British military occupation.

I think the very fact that Palestine was coming under a British military occupation was also a game changer in Britain’s conception of their rights and claims to Palestine. All very well for Russia and France to be saying, this has got to be internationalized. For the British, there was a sense that their claim was now higher for the two failed attempts on Gaza with high British casualties, and then the numbers that they’d suffered in finally breaking through and in conquering Palestine.

So I think it’s not a question of when should Balfour have made his claim. Once they’d broken through Ottoman lines and were advancing into Palestine, Britain wanted to really start to stake its claim to Palestine, to change the formula that Sykes – Picot had put down between Britain and France in particular. Russia was now a little more marginal because of the Bolshevik seizure of power, and then moving into a position of not taking interest in extra territorial empire.

So here, I think that’s part of why they were so hasty. Even in that, remember, they may be pushing the Ottomans back in Palestine, but there was no reason in December of 1917 to anticipate that the British and French would defeat Germany or win the First World War.

So in a sense, it’s still in a terrain of trying to advance partition diplomacy under great uncertainty of whether any of that partition diplomacy would be acted on. If Britain and France lost the war, if Germany and its allies won, then the Ottoman Empire would be talking about getting back Cyprus from the British and, you know, claiming islands back from Greece and a whole different discussion would have been going on. You just couldn’t know what the outcome would be.

So think of it really, not as Balfour imposing Britain’s will on anyone other than the French and trying to rewrite the partition diplomacy to firmly stake their claim on Palestine and to do so in the name of the Zionist movement so that the French couldn’t argue that the British were, you know, driven by their own Imperial interests. That would have complicated Anglo-French relations.

Diana:

I have an interesting follow-on question from Brian Chapman, “I understand the reason behind Britain looking to get Jewish support in 1917, some of the things you just touched on, but once the war was won in 1918, why didn’t they just backtrack at that point?”

Eugene:

Well, this is where my argument that the Zionists become the Maronites of the British and Palestine is, I think, the new takeaway from my talk. This idea… to me, the reason I chose the milestones I did, is because they really help us frame the limits that Britain wanted to put on the Zionists’ national home project to advance their own imperial interests in governing Palestine. So, you know, I think each of those milestones: ’22; Churchill; not a Palestine as Jewish as England is English… it’s already setting out. We’re looking at a kind of minority situation here. Partition is always taken as a moment where the British show their hand: look, they’re giving Palestine to create a Jewish state. But really, I mean, the kind of independence treaty that Britain was conceding in the 1930s – and look at the Iraqi and the Egyptian documents – is really just a “rebrokering” of the colonial situation.

And then you come to ’39, where they abandon partition and they limit Jewish immigration in such precise ways to keep them 35%. You know, what a convenient, compact minority, totally dependent on Britain, surrounded by enemies, hostile powers, you know, and in control of key territory and an economic infrastructure. That was the essential part for making the Palestine mandate work. And that’s why the British were willing to encourage the expansion of the Jewish community up to that 35% marker.

But the 1939 white paper to me really, you know, clinches my argument for the Zionists as the Maronites of Palestine. It’s when they revolt against the British that the whole British project in Palestine collapses, because you don’t have your dependent and reliable partner community anymore. They’ve surged towards a critical mass. They’re becoming a majority, and they’re going to bid for their own independence just as the British always feared they would if they were allowed to go beyond 35%.

So, I mean, I hope that argument makes sense. It’s funny, but that’s not the way the story is written now, and I think it should be. I think, by situating Palestine within its British imperial context, we can so better understand how it really was Britain trying to manipulate the Zionist movement and the Zionists outplaying the British in that game,

Diana:

It definitely is a very interesting perspective and way to frame it all.

I’ve got a question from Isabel Miller: “As I remember it, Professor Malcolm Yapp used to say that there was more emigration from Palestine by Jews than immigration to Palestine. In other words, Jews who went there in the ‘20s and ‘30s didn’t stay. Do you disagree with this?”

Eugene:

It’s funny. I remember those arguments being made more for the first couple of waves of immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th century that were encouraged by the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association of the Rothschilds and by the Montefiore philanthropic enterprise. And that there was a higher degree of out-migration, just because the idealists of the Eastern European Zionist movement really didn’t know what they were in for in Palestine and found it harder to make it work than they’d anticipated. Lots of them left.

I don’t know about out-migration in the 1920s, but certainly in the 1930s there were reducing numbers of options open to European Jews facing what the more astute recognized was, increasingly, the existential threat of Nazi Germany.

So, you know, the kind of numbers we saw that turned immigration critical in the 1930s, particularly from Germany or territories near Germany where people feared for their future, was of Jewish communities that were not subject to out-migration. Once they got to Palestine, it was their safehaven and they become a core of the sort of New Yishuv that would be important for the development of a military force out of the Haggadah and for creating a critical mass that would then go to work in 1944/45 to try and change the demographic balance. As the realities of the post-war world, including the Nazi murder of Europe’s Jews through the Holocaust, or the Shoah, would be a key driver.

Diana:

We have some comments from Tony Greenstein who says that there was a financial collapse that contributed in the ‘20s to many Jews leaving Palestine. That’s also an area that I don’t know very much about, so that would be maybe in another webinar. I’ve got a question from Professor Mahmood Mussa, “It is obvious that Arabs are victims of the empire,” he says. “Would you say that Israeli Jews are also victims?

Eugene:

Well, I think in my telling of the story, there was a willful manipulation of the Zionists by the British and of the British by the Zionists, both thinking that they were advancing their goals and ultimately it was the Zionists who won out. Had they been kept to a compact minority, a sort of despised agent of imperialism in an independent Palestine after 1949 had the 1939 white paper been realized, for instance, then one might have made the case that the British were exploiting the Zionists in a way which was harmful to their interests. You know, not letting them reach a critical mass, keeping them confined to this partner status that left them exposed to attacks and hatred and whatnot by the surrounding Arab community in Palestine.

As it turned out, the Yishuv, in the course of the revolt, was very successful in making Britain’s position in Palestine untenable and driving them out. So in my reading, I would say the Zionists prevailed over the British in securing their political ambitions.

Diana:

Following on from that, Christopher Ward says: “Many British serving in Palestine found the Yishuv quasi-communist. Didn’t this affect British policy?”

Eugene:

That’s a really interesting question because there certainly was one strand of Zionist thinking that had a very strong socialist component. If one looks at the debates in America, in Russia, the Soviet Union about recognizing Israel’s declaration of statehood, there really was a question of which way this new state would head. Would its socialist roots lead it more in line with the Soviet Block? Or would its origins as a British colony incline it more towards a more European and American model?

So I think that was a question mark, but aside from the collective farming, the Jewish middle-class in Palestine was sufficiently assimilated to capitalist markets and whatnot to reassure the British that they didn’t see themselves establishing, if you would, “the Peoples Soviet of Zionist Palestine.”

It was clearly one of many ideological strands that shaped the politics of the Yishuv, but it’s important to say the Yishuv was not a homogenous body. The Zionist executive was rife with debates among its members about their priorities and their politics and so it’s important to remember that among those politics were very strong communist and socialist ideals, many of them coming from the Eastern European experience.

Diana:

I’ve got a question from Mike Joseph and I’m asking this question, because again, this is a topic that came up a lot during our conference and I thought it was a very interesting point. “Would you comment on Martin Gilbert lecturing in 2011 and some of our speakers at our conference last week: the centerpiece of British policy – that Britain would withhold representative institutions to Palestine for as long as there was an Arab majority – this argues that Britain explicitly intended a future Jewish majority with a democratic voice while ensuring native Palestinian societies would never obtain such a strong voice. Do you have any comments on that?”

Eugene:

Well, it’s a good complicating factor that I am going to need to work into my parsimonious model because in talking about the idea of reaching parity – in other words, where you’d have equal sized communities – it would suggest that the British were entertaining the idea of going beyond a compact minority of, say, 35%. But it might also reflect a British will to prevent having to go to representative institutions altogether, because you could make that the condition for having a council and then never let the Jewish community reach the parity that would make it happen. I’d be keen to look at that further. Thank you for the comment.

Diana:

From Mathew Madain: “Histories of American foreign policy largely mention Palestine in the post-WWII era. Were the Americans largely supportive of Britain’s imperial project in Palestine in the interwar period?”

Eugene:

Well now, Mathew Madain is no stranger to Oxford’s Middle-East Centre, or indeed to me We worked together just last year while he was a master’s student here. So excellent to have you with us, Mathew, glad to be reaching from Oxford all the way to the west coast of the USA.

And you’ve asked me a question that I actually don’t know the answer to. What a sad way to end the presentation. I don’t really know of America having taken an active position until you get to the UN Commission’s examining of the plans for Palestine in 1946/47 and the Americans’ role in that, by which point, I think, the Americans are beginning to show some concerns for the partition plans that were put in place by the UN. And we know that the Americans tried to pursue a reversal of the partition resolution of 29th November, 1947. But where the Americans were in the 1920s and 30’s? I’ve just never read about that. It would seem to me, probably, an area – because it’s a colonial matter and sort of outside of America’s diplomacy – was probably not looming large.

But I don’t know more about it than that, Mathew, and shame on you for putting me to shame with a question I couldn’t answer!