House of Lords, 21 June 1922

By William M Mathew

Contents

PART I

On 21 June 1922, following his elevation to the peerage a few weeks earlier, Arthur Balfour – now the Earl of Balfour – delivered his maiden speech to the House of Lords, this in response to a motion in the name of Lord Islington (John Poynder Dickson-Poynder, 1866-1946; governor of New Zealand, 1910- 12; war-time under-secretary-of-state for India) that:

`The Mandate for Palestine is unacceptable to this House, because it directly violates the pledges made by His Majesty`s Government to the people of Palestine in the Declaration of October, 1915 [”Great Britain is prepared to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories included in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif”], and again in the Declaration of November, 1918 [“The object of war in the East on the part of Great Britain was the complete and final liberation of all people formerly oppressed by the Turks…”], and is, as at present framed, opposed to the sentiments and wishes of the great majority of the people of Palestine; that, therefore, its acceptance by the Council of the League of Nations should be postponed until such modifications have therein been effected as will comply with pledges given by His Majesty`s Government`.

In the course of a long speech, prefaced by extravagant praise of the ennobled Balfour (`this House has not experienced a similar or comparable occasion since the day, now over half a century ago, when Lord Beaconsfield [Disraeli], on his translation from another place, first addressed your Lordships` House`), Islington moved debate on the terms of the proposed Palestine Mandate in advance of any ratification by the Council of the League of Nations, noting the words of article 22 of the Covenant of the League that `the wellbeing and development` of the former subject peoples had to be clearly affirmed, and that the mandatory Powers had to render `administrative advice and assistance` to these communities `until such time as they are able to stand alone`.

Islington`s argument was that a privileged Jewish Home in Palestine would stand in contradiction to such principles, imposing on the United Kingdom `the responsibility of trusteeship for a Zionist political predominance where 90 per cent of the population are non-Zionist and non-Jewish`. He quoted the recent judgement of the colonial secretary, Winston Churchill, that any such commitment `conflicted with our regular policy of consulting the wishes of the people in mandated territories and giving them a representative institution as soon as the peoples were fitted for it` – and cited the cases of Iraq and Egypt where `self-government has been established`. Why the delay for Palestine?

`One can draw only one conclusion`, Islington suggested, `and that is that before self-government is given to Palestine time must be allowed for that amount of immigration of the Jewish community to take place which will enable the system of self-government to be based upon a Jewish Constitution`.

The strictly political problem had been compounded by the recent concession to the Ukraine-born Zionist, Pinhas Rutenberg, of monopoly rights for the generation of electricity from the Jordan and Oudja rivers, thus awarding `a Jewish syndicate wide powers over the economic, social and industrial conditions of an Arab community…for no less than seventy years` – in the process ignoring `a whole stream of quite reliable applications…from native sources in Palestine` in line with `a deliberate policy of economic preference to the Zionists`.

`This scheme`, Islington concluded, `of importing an alien race into the midst of a native local race… is an unnatural, partial and altruistic experiment, and that kind of experiment is a very grave mistake today, wherever it is tried, and particularly in the East and among Eastern peoples….During the last four years His Majesty`s Government have made many well-meaning efforts towards social and racial reconstruction. Some of them have succeeded; others have not been so successful. I venture to suggest that the fault in almost every case has been that their schemes have been too precipitate, that they have not waited for a deliberate discussion in which all sides of the question could be considered, and attention brought to bear upon the efficacy of the proposals made….I would earnestly appeal to His Majesty`s Government to apply the “Geddes Axe” [proposed retrenchment in British government expenditure] to Zionism in Palestine, and to constitute in its place a national system. I am convinced that it will have to be done sooner or later. Surely it is wiser to do it now, instead of waiting for it to be the outcome of revolt and, possibly, bloodshed`.

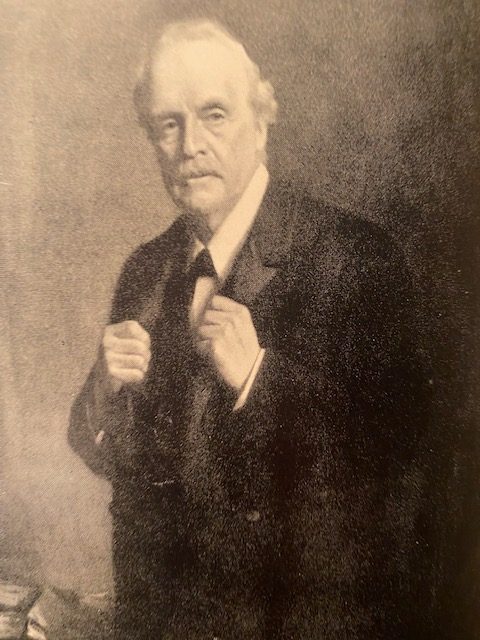

PART II: The Lord President of the Council (The Earl of Balfour)

This was the first occasion on which Balfour, a few weeks short of his 74th birthday, presented a detailed justification in parliament of the government`s National Home policy – more than four-and-a-half years on from his Declaration. The speech (little featured in the recent literature) carries its own distinctive linguistic flavour – Dennis Judd (Balfour and the British Empire [1968]) noting that Balfour was a man who `frequently thought while on his feet. He rarely made copious notes for speeches, and those he did produce were often scribbled on the backs of envelopes`. Delivered from the assured self-regard of a high-born past prime minister and foreign secretary, his Lords speech came with a grandiosity of expression, emotive accusation, and false binaries – Balfour adept at generating his own fog of political battle. He displayed a tendentious failure to identify, far less address, any of the contradictions and provocations that large numbers of individuals, in government and beyond, in Britain and Palestine, had recently identified in the Zionist commitment – not least the findings of two official commissions of inquiry headed by Sir Philip Palin (1920) and Sir Thomas Haycraft (1921): the former referring to a `native population, disappointed of their hopes, panic- stricken as to their future`; the latter identifying Arab grievances `too genuine, too widespread, and too intense` to be ignored. And there was no attempt on Balfour`s part to harmonise with the concerned perceptions of his government colleagues, in particular Lloyd George and Winston Churchill.

In objecting to the fact – as he fallaciously claimed – that parliament had never previously considered the issue of Palestine and its governance, Balfour displayed what Piers Brendon (Eminent Edwardians [1979] calls his characteristic `lackadaisical ignorance`. Lord Curzon, his successor as foreign secretary, considered him `the worst and most dangerous` individual to have held the office, writing of his `lamentable ignorance, indifference, and levity….He never studied his papers; he never knew the facts; at the Cabinet he had seldom read the morning`s FO telegrams; he never got up a case; he never looked ahead` – trusting instead to `his unequalled power of improvisation`.

Concerning Palestine, his performance was, to use Scott Fitzgerald`s phrase, one of `vast carelessness`. Balfour`s assertion in the Lords that he had `not read these [parliamentary] orations…due to the fact that I have, unfortunately, spent so much of the time outside the frontiers of this country` – referencing his work at the Paris Peace Conference and, later, at the League of Nations and the Washington Naval Conference – has an obvious validity. It might have been expected, however, that he of all people, having authored the Declaration and led the Foreign Office until October 1919, would have at least kept a curious eye on the intense controversies that had developed around his Palestine policy over the previous four years. It was as though no-one had uttered a word of concern until that very day in the chamber.

The fortunes of the resident Arab majority in Palestine were, his speech confirms, of scant interest to him. A.L. Tibawi writes (Anglo-Arab Relations and the Question of Palestine 1914-21 [1978]: `He was fully aware of the Arab opposition to his policy but decided to ignore it completely` – this contrasting with the alertness to Arab sensitivities shown by his Zionism-supporting colleague Winston Churchill in a Commons debate of the previous June, specifying the `ardent declarations of the Zionist organisations throughout the world…of their hope and aim of making Palestine a predominantly Jewish country`, thereby having `greatly alarmed and excited the Arab population` and its sense of `Arab nationality`. Balfour would never have used such language. Indeed, he thought, in his casual dismissiveness, that such people should be showing due appreciation to Britain for their liberation from Turkish rule. Any worries as to their possible subordination to Zionist power were dismissed, three times in his speech , as `fantastic` – this despite his written approval of a 1917 Foreign Office draft which had stated that `Palestine should be constituted as the national home of the Jewish people`. As Jason Tomes (Balfour and Foreign Policy [1997] notes, `There was no ambiguous “in Palestine”, here, nor any mention of the rights of non-Jews`. ( The same sort of discriminatory racist mindset appears in his earlier perceptions of Ireland, where he served as chief secretary between 1887 and 1891 – contrasting the sturdy and industrious Protestants of the North with the inert Catholic majority who had been happy to `squat generation after generation on the bogs of the inclement West`. Catherine B. Shannon (Arthur J. Balfour and Ireland 1874 1922, 1988) writes of his `consistent tendency to view Irish history through the prism of condescending and racialist British Imperial values`, citing his declaration in Parliament: `Before English power went to Ireland , Ireland was a collection of tribes waging constant and internecine warfare, without law, without civilization. Although the law is imperfectly obeyed…all the law, and all the civilization in Ireland is the work of England.` There was some family form here, his aunt, Lady Salisbury, having stated a long-held and `intimate conviction that the only cure for the evils of Ireland is the total extermination of the inhabitants…`.)

In the debate, Balfour declared, startlingly, that he could not, `imagine any political interests under greater safeguards than the political interests of the Arab population of Palestine`. These were the very interests, of course, that had been deliberately omitted from his 1917 Declaration, in which only `civil and religious rights` had been specified. `Balfour`s dialectical chicanery`, writes Brendon, `was such that he even bamboozled himself`.

His House of Lords argument was, in its highly mannered content and drift, strangely apolitical – strange, that is, from someone who had traded in political conflict, compromise, and posture since he first entered parliament almost a half-century before, and had held the highest of political offices, notably as, successively, Ireland secretary, prime minister, and foreign secretary. The presentation is essentially idealistic in the neutral sense of the term, the ideas in play forming a dialectic, not of prospective Jewish polity and Arab polity, but, more narrowly, of Jewish suffering and Jewish genius.

As for serious political commitment, in any cause, he was, as he casually observed of himself, `a thick and thin supporter of nothing, not even of myself`.

A.J. P Taylor refers to him as `cynical, unprincipled, and frivolous`- the latter characteristic notably exemplified in his exchanges with the French ambassador in London during the war, Paul Cambon. When Balfour declared `that it would be an interesting experiment to reconstruct a Jewish kingdom` in Palestine and Cambon warned that, according to scripture, a Jewish king would signify the end of the world, Balfour`s arcane-facetious response was `that such a denouement would be even more interesting`.

My Lords [the speech here being only marginally trimmed, to remove excess verbiage], I am sorry that I was not present at the opening remarks of my noble friend who has just sat down. I was unavoidably detained by circumstances which your Lordships will easily conjecture, and I could not be in my place when my noble friend rose….I do not think that I have lost any essential points of my noble friend`s case. As I understood him, he thinks, in the first place, that the Mandate for Palestine is inconsistent with the policy of the Powers who invented the mandatory system, who have contrived the mandatory system, and who are now carrying it into effect. That is his first charge. His second charge is that we are inflicting considerable material and political injustice upon the Arab population of Palestine. His third charge is that we have done a great injustice to the Arab race as a whole.

I should like to traverse all these statements….The mandatory system always contemplated the Mandate for Palestine on the general lines of the Declaration of November, 1917 [but not on the general lines of Mandate policy elsewhere]. It was not sprung upon the League of Nations….It was a settled policy among the Allies and Associated Powers that met together in Paris to deal with the peace negotiations….As for this country, I happened to be the mouthpiece of my colleagues in making the Declaration of November, 1917. I do not know why we have waited – I do not know why your Lordships` House has waited – until 1922 to attack a policy which was initiated in 1917 or before [an extraordinary charge, later rebutted by Lord Islington: see below], which was plainly before the world and was dealt with in detail in 1919 in Paris, and is now being carried out by the Allied and Associated powers and by the League of Nations [though in 1919 he himself had described as `flagrant` the `contradiction between the letters of the (League) Covenant` and British Palestine policy].

I will come to his more particular charges. These particular charges were in the first place, as I understood him, that it was impossible to establish a Jewish home in Palestine without giving to the Jewish organisations political powers over the Arab race with which they should not be entrusted, and which, even if they exercised them well, were not powers that should be given under a British Mandate to one race over another. But I think my noble friend gave no evidence of the truth of these charges. He told us that it was quite obvious that some kind of Jewish domination of the Arabs was an essential consequence of the attempt to establish a Jewish Home….I cannot imagine any political interests under greater safeguards than the political interests of the Arab population of Palestine [Balfour himself having declared that `Zionist aspirations in Palestine are of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land`, making it clear that Britain did `not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country`].

Every act of the Government will be jealously watched. The Zionist organisation has no attribution of political powers. If it uses or usurps political power it is an act of usurpation. Is that conceivable or possible under the lynx eyes of critics like my noble friend, or of the Mandates Commission, whose business it will be to see that the Mandate is carried out, or of a British Governor-General [the mis-titled Zionist High Commissioner, 1920-25, Herbert Samuel – `I presume`, wrote Hubert Young of the Colonial Office, ` that the idea in appointing a Jew as the first Head of the new administration in Palestine is to make it clear that H.M.G. really propose to carry out their Zionist policy…`] nourished and brought up under the traditions of British equality and British good government, and, finally, behind all these safeguards, with the safeguard of free Parliamentary criticism in this House and the other House? These are fantastic fears [despite his prime minister, Lloyd George, accepting that same year that: `The Arab race, its pride, its sense of justice and fair play has been outraged by the feeling that somehow or other things have not quite been done in the way they had expected`]. They are fears that need perturb no sober and impartial critic of contemporary events, and whatever else may happen in Palestine, of this I am very confident: that under British Government no form of tyranny, racial or religious, will ever be permitted.

Now, I go from that broad charge of putting the Arab population under the domination of the Zionist organisation, and I come to the more detailed attacks made by my noble friend. He criticised the whole system of immigration. I do not know why he did that. No human being supposes that Palestine is an over-populated country. It is, I believe, an underpopulated country at the moment at which I speak, before all the economic developments to which I look forward have had time to take place, and if the hopes that I entertain are not widely disappointed, the power of Palestine to maintain a population far greater than she had, or could ever have, under Turkish rule, will be easily attained in consequence of the material well-being which under Turkish rule were wholly impossible….

The hopes that I have just expressed…with regard to the numbers it could support, of course are based, and necessarily based, upon the amount of capital expenditure, and upon the character of the Government under which all these operations will be carried out.

Now, I ask my noble friend, who takes up the case of the Arabs, and who seems to think that their material well-being is going to be diminished under the new system, how he thinks that the existing population of Palestine, of whom he has – very rightly from his point of view – constituted himself the advocate in this House, is going to be effective unless and until you get capitalists to invest their money in developing the resources of this small country – small in area, though great in memories – which according to all the information we possess, might carry a population far bigger – I will not venture to give figures, but far bigger – than that which it now supports. But it can only do so, I believe, if you can draw on the enthusiasm of the Jewish communities throughout the world [an entirely speculative and crudely developmental argument, exclusively Jewish in emphasis, and devoid of any economic or demographic measurement, or appraisal as to how inter- community relations might develop politically – beyond, presumably, Arab gratitude and submission]. As soon as all this Mandate question is finally settled, as soon as all the existing legal difficulties have been got over, they will, I believe, come forward and freely help in the development of a Jewish Home….

I am not going in detail into the Rutenberg controversy….But I can tell my noble friend that this whole scheme was examined in the most critical spirit by the experts of the Colonial Office, and that they were quite unanimous that the terms…were such that you could with no prospect of success hope for any better contract being made than that which was offered to Mr Rutenberg….I was rather surprised at the whole tenor of my noble friend`s criticism….The first charge is that there is favouritism in giving the contract [which had not been put out to competitive tender, and was awarded to a Zionist], the second that when the contract is accomplished and the works are finished, there will be favouritism in their employment as between different sections of the population. I can hardly believe that my noble friend seriously thinks that that possibility can occur. Palestine is no vast area….It is small in extent, it is under the eyes of the Government officials from end to end, from East to West, from North to South, from Dan to Beersheba; and the notion that this great scheme, sanctioned by the Government, is going to be used as a method of oppression by those who have found the money against those for whom the money is to be used, seems to me one of the most fantastic accusations ever made, here or elsewhere….But if the populations who were trampled under the heel of the Turk until the end of the war are really to gain all the benefits that they might, it can only be by the introduction of the most modern methods, fed by streams of capital from all parts of the world, and that can only be provided, so far as I can see, by carrying out this great scheme which the vast majority of the Jews – not all, I quite agree, and very often, perhaps commonly, not the wealthiest – the great mass of the Jews in East and West and North and South believe to be a real step forward in the alleviation of the lot which their race has had too long to bear [a switch in the argument from Palestine requisites to Jewish suffering]. I do not think I need dwell upon this imaginary wrong which the Jewish Home is going to inflict upon the local Arabs.

But that is not the only charge which my noble friend made. He told us that we were doing a great injustice to the Arab race as a whole, and that our policy was in contradiction of pledges given by General [sic] MacMahon and the Anglo-French Declarations conveyed to the native populations by General Allenby. Of all the charges made against this country I must say that the charge that we have been unjust to the Arab race seems to me the strangest.

It is through the expenditure of British blood, by the exercise of British skill and valour…in the main that the freeing of the Arab race from Turkish rule has been effected. And that we, after all the events of the war, should be held up as those who have done an injustice, that we, who have just established a King in Mesopotamia, who had before that established an Arab King in the Hejaz [these very concessions, as Islington indicated, serving only to highlight the comparative political deficit imposed on the Arabs in Palestine], and who have done more than has been done in centuries past to put the Arab race in the position to which they have attained – that we should be charged with being their enemies, with having taken a mean advantage of the course of international negotiations, seems to me not only most unjust to the policy of this country, but almost fantastic in its extravagance. [Nowhere in his circumlocution does Balfour visualise any sort of equitable Arab-Jewish polity: implicit is the notion of an impending Jewish state. The separation of the communities is clearly suggested by his idea, set out some years earlier, of the `small notch` that Arabs, allegedly rich in land, would `not grudge` handing over to the Jews as their exclusive territory.]

Again I would ask: Why is it that now, for the first time, towards the end of June in 1922, we hear these accusations? If they have any basis at all that basis was as strong three years ago, or four years ago, as it is now. My noble friend has kept silent for those years [at which point Lord Islington interjected: `No; we have had six debates on this subject, and possibly more` (for example, in June 1921, in both Houses)]. Then I am sure my noble friend must have very thoroughly covered the ground, and I really most respectfully apologise for the fact that I have not read these orations. It was entirely due to the fact that I have, unfortunately, spent so much of the time outside the frontiers of this country….

I think I have traversed the main lines of my noble friend`s attack….I see no reason [ignoring those enumerated at length in the official Palin and Haycroft reports of 1920 and 1921] why those who lived, according to my noble friend himself, in amity under Turkish rule should insist on quarrelling under British rule. I hold that from a purely material point of view the policy that we have initiated is likely to prove successful policy. But we have never pretended, that it was purely from these materialistic considerations that the Declaration of November, 1917, originally sprung. I regard this not as a solution, but as a partial solution of the great and abiding Jewish problem.

My noble friend told us in his speech, and I believe him absolutely, that he has no prejudice against the Jews. I think I may say that I have no prejudice in their favour. But their position and their history, their connection with world religion and with world politics, is absolutely unique. There is no parallel to it, there is nothing approaching to a parallel to it, in any other branch of human history. Here you have a small race originally inhabiting a small country [but long ago succeeded, as his cabinet colleague Lord Curzon had pointed out, by Arabs whose `forefathers have occupied the country for the best part of 1,500 years`]. I think of about the size of Wales or Belgium, at any rate of comparable size to those two, at no time in its history wielding anything that can be described as material power, sometimes crushed in between great Oriental monarchies, its inhabitants deported, then scattered, then driven out of the country altogether into every part of the world, and yet maintaining a continuity of religious and racial tradition of which we have no parallel elsewhere.

That, itself, is sufficiently remarkable, but consider…how they have been treated during long centuries…how they have been subjected to tyranny and persecution; consider whether the whole culture of Europe…has not from time to time proved itself guilty of greater crimes against this race. I quite understand that some members of the race may have given, doubtless did give, occasion for much [sic] and I do not know how it could have been otherwise, treated as they were; but if you are going to lay stress on that [no- one, Balfour apart, was conveying anti-semitic asides in the debate], do not forget what part they have played in the intellectual, the artistic, the philosophic and scientific development of the world. I say nothing of the economic side of their energies, for on that Christian attention has always been concentrated….You will find them in every University, in every centre of learning; and at the very moment when they were being persecuted by the Church, their philosophers were developing thoughts which the great doctors of the Church embodied in their religious system. As it was in the Middle Ages, as it was in earlier times, so is it now.

And yet, is there anyone here who feels content with the position of the Jews? They have been able, by this extraordinary tenacity of their race, to maintain this continuity, and they have maintained it without having any Jewish Home. What has been the result? The result has been that they have been described as parasites on every civilisation in whose affairs they which mixed themselves – very useful parasites [sic] at times I venture to say. But however that may be, do not your Lordships think that if Christendom…can give a chance, without injury to others [the central concern for Palestine, dismissed in a phrase], to this race of showing whether it can organise a culture in a Home where it will be secured from oppression, that it is not well to say, if we can do it, that we will do it. And, if we can do it, should we not be doing something material to wash out an ancient stain upon our own civilisation if we absorb the Jewish race in friendly and effective fashion in those countries in which they are the citizens [hardly the spirit of his anti-Jewish 1905 Aliens Act when prime minister, or in accord with his 1919 observation that Jews comprised `a Body` creating `miseries…for Western civilisation…which it was … unable to expel or to absorb`].

It may fail. I do not deny that this is an adventure. Are we never to have adventures? Are we never to try new experiments [in someone else`s land]. I hope your Lordships will never sink to that unimaginative depth, and that experiment and adventure will be justified if there is any case or cause for their justification, surely, it is in order that we may send a message to every land where the Jewish race has been scattered…that we desire to the best of our ability to give them that opportunity of developing, in peace and quietness [no sense whatsoever of inter-community conflict, already much in evidence] under British rule, the great gifts which hitherto they have been compelled from the very nature of the case only to bring to fruition in countries which know not their language, and belong not to their race. That is the ideal which I desire to see accomplished, that is the sum which lay at the root of our policy I am trying to defend; and though it be defensible indeed on every [sic] ground, that is the ground which chiefly moves me.

PART III

In ensuing speeches, Lord Sydenham (George Sydenham Clarke, 1848-1933; successively governor of Victoria and Bombay; later a vocal anti-semite and fascist sympathiser) praised Balfour`s `very eloquent and forcible` remarks, but objected , like Islington, to his claim `that the question of Palestine has never before been raised in this House. It has been raised many times, and nearly the whole story of the difficulties, and, as we think, the injustices, upon the Palestinians has been already told. Palestine was not the original home of the Jews. It was acquired by them after a ruthless conquest, and they never occupied the whole of it….They have no more valid claim to Palestine than the descendants of the ancient Romans have to this country`. If such assertions were to be admitted, `the whole world will have to be turned upside down`.

Lord Buckmaster (Stanley Owen Buckmaster, 1861-1934; lord chancellor in the Asquith government, 1915-16), following, claimed that Balfour had departed `from what appeared to me to be the correct and rather dusty road of debate and wandering into the pleasant pastures of history and philosophy, and partly, I think, of religious discussion with regard to the origin and the action of the Jews`. If the issues under debate were not so serious, he would have had pleasure `in joining him in those wanderings…and in all his new idealistic adventures…`.

Balfour was congratulated by Lord Lamington (Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 1860- 1940; successively governor of Queensland and Bombay; commissioner of British Relief Unit in Syria 1919) `on the dialectical skill with which he skimmed over thin ice` thereby failing to acknowledge `the breach of pledges given to the Arabs at the time when we so urgently needed their help`. He `did not come to close quarters` with the troubling fact, evident from Lamington`s own recent visit to Palestine, that the Mandate in its current form `gave an overwhelming strength to Zionism or the Zionist Organisation`.

The debate concluded with Lord Willoughby de Broke (John Verney, 1896- 1986; former aide-de-camp to the governor of Bombay) claiming that, having listened to Balfour, he almost wished `that I was a Jew myself because they came in for some very handsome treatment at his hands`.

And so the exchanges ended. Remarkably, not one of the assorted peers who opposed the motion – including the lord chancellor Viscount Birkenhead and an earlier foreign secretary, the Marquess of Lansdowne (Balfour had been his fag at Eton) – stood up to declare in the lord president`s support: on his side of the debate, his was the solitary voice.

The House divided, Islington`s motion being carried by a margin of to 60 to 29. It had no effect on the finalisation of the Mandate two years later. The `experiment` continued unamended.

Suggested Further Reading

India, Palestine and the Balfour Declaration

Balfour 1922-23: Fragile commitment and Zionist Response

Rescuing Balfour: Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office 1921-22

Joseph Jeffries and the ‘Palestine Deception’, 1923