How the Zionists hitched a ride on the Imperialist bandwagon

By William M Mathew

It was fundamental folly to annex Palestine out of persistent anxieties over imperial, notably Indian, security, while at the same pursuing therein a policy of Zionist settlement that, through resulting ethnic conflict, served to render the territory almost useless as an imperial asset. Its strategic value was uncertain in any event given the wide geographical separation of Palestine and India and the weakening of British control in the subcontinent in the face of intensifying political and economic nationalism. The folly, in its various dimensions, being then widely recognised, fits Barbara Tuchman’s (The March of Folly) criterion that `the policy adopted…must have been perceived as counter-productive in its own time’.

The United Kingdom’s strategic priorities have not been much appraised in Zionism historiography, much of it markedly introverted and non-contextual on wider issues of imperialism; and general writings on imperial history seldom mention tiny Palestine in any detail, with the critical Palestine-India link barely identified. This piece attempts to reduce the analytic deficit, setting British Palestine policy in its broad global frame.

Two prime ministers, heavily involved in their different ways in Levantine policy, offered bleak reflections in the 1940s. For Winston Churchill, British rule had been `a painful and thankless task`, yielding not `the slightest advantage` for the home country; for Clement Attlee, it had been a decidedly `wild experiment`, conceived in `a very thoughtless way` – the interests of Arabs and Jews being ‘quite irreconcilable`.

Contents

I. Zionism and Empire

A. The Centrality of Imperialism

B. India: The Critical Context

C. The Imperial Mind: India, Suez, and Palestine

D. ‘Strategical Zionism’ and ‘The Seventh Dominion’

II. British Palestine and ‘The March of Folly’

A. Contemporary Anxieties

B. Ethnic Questions

C. The Fading Jewel

D. In Sum

Part One: Zionism and Empire

A. The Centrality of Imperialism

The proposition here is that the Zionist project, as defined in the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917, could not have been enacted without the British seizure of Palestine (incomplete at the time of the Declaration) from its Ottoman masters – but that the annexation itself, being India-prompted, was not undertaken to facilitate that enactment. This initial split focus has had century-long consequences. It proved folly to believe that both goals, the primary imperial (in its strictly political-annexationist sense) and the secondary Zionist, could be simultaneously pursued to good effect, the two only coming together, subjectively, in the fanciful idea of `strategical Zionism`.

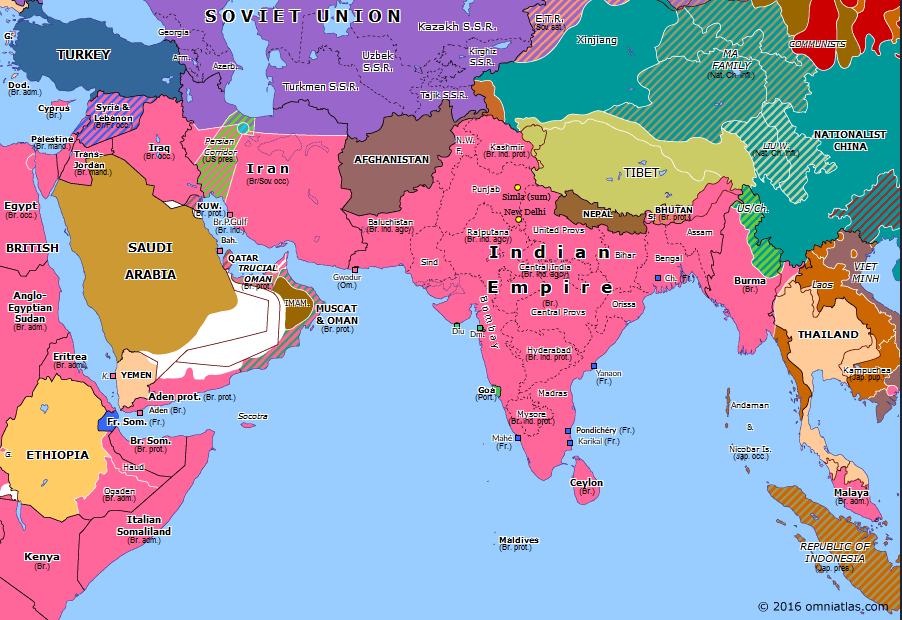

A related purpose is to bring Palestine within the orbit of the Ronald Robinson & John Gallagher argument (Africa and the Victorians [1961]) that for United Kingdom statesmen `India and the British Isles were the twin centres of their wealth and strength in the world as a whole`. Throughout the nineteenth century `it seemed imperative to make sure of the communications between the British Isles and India, if the spine of prosperity and security was not to be snapped. British positions and interests in half the world stood or fell upon the safety of the routes eastward`.

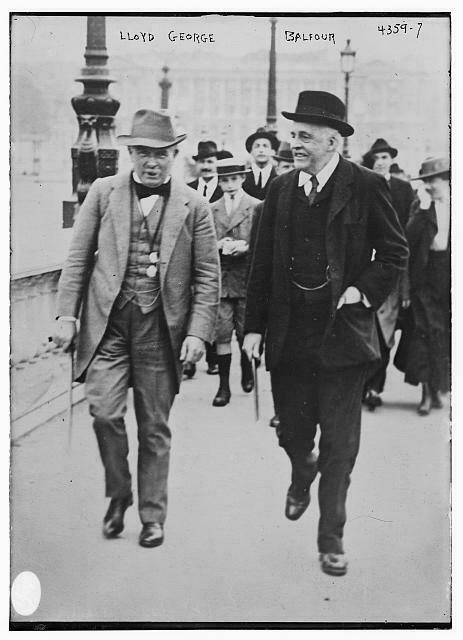

In that critical month of November 1917, War Cabinet Minutes show that the issue of a Jewish national home featured not at all in that central body`s deliberations on Palestine. The military and strategic aspects of British interest there, abutting as it did on Egypt and, more specifically, Suez, and thereby concerning India, featured, however, at as many as 17 separate meetings between the 2nd and the 30th. Stephen Roskill, biographer of the powerful head of the War Cabinet secretariat, Sir Maurice Hankey, notes (Hankey: Man of Secrets [1970]) how Hankey`s diaries for early November make no mention of the Balfour Declaration, explaining `the seemingly casual way` in which it was approved by the fact that `all the War Cabinet were at the time deeply involved in preparing for the historic Rapallo Conference` – to which meeting Lloyd George and his delegation departed the day after the Declaration was issued. The broad context of national and Empire security in time of world war was decisive. The suffering of European Jewry would not by itself have taken the British into Palestine. Zionism could never have trumped imperialism.

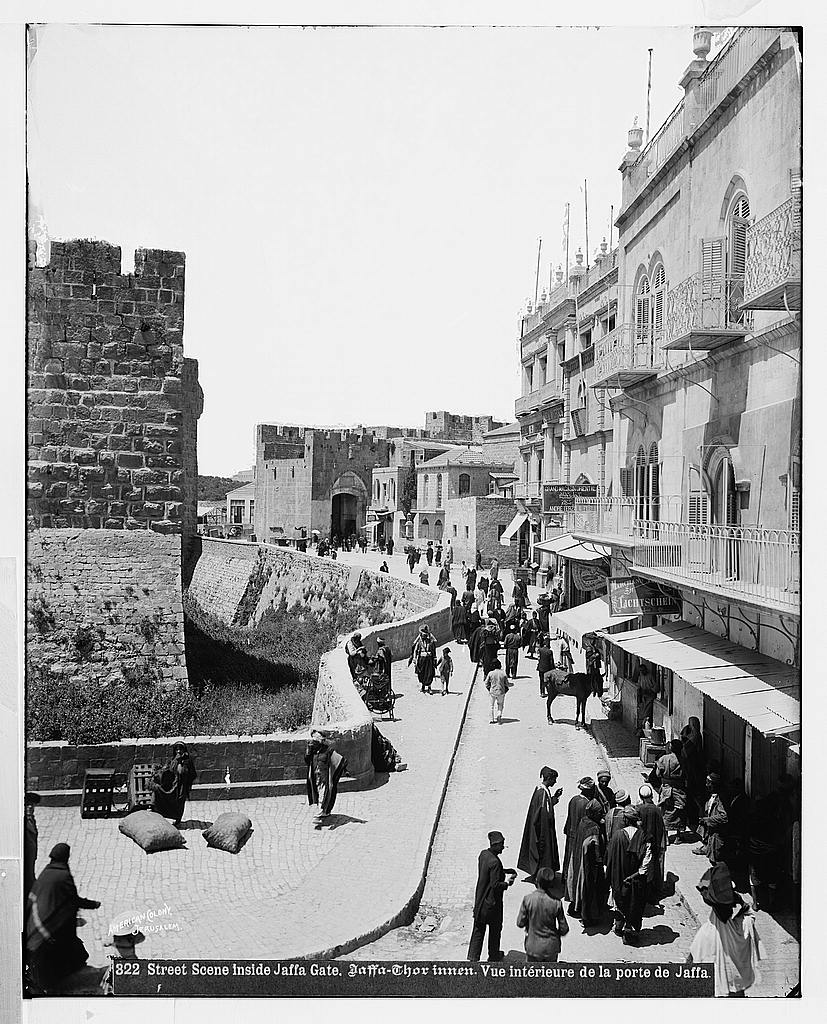

As with so many British acquisitions in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, any material attractions of the territories themselves counted for less than did their geographical location in relation to London`s international ambitions and anxieties. Such places, in consequence, were usually taken over in conditions of comparative ignorance, resulting in policies often ill-conceived in relation to local political and social circumstance. Concerning Palestine, the journalist Joseph Jeffries posed the question (Palestine; The Reality [London, 1939]): `What in 1917 did the war-torn British public, what did the deluded Jews of Russia, what did the general body of people outside the Near East know about the composition of the population of Palestine?` His answer: `Nothing`.

And ignorance bred contempt. Sir John Glubb of the Arab Legion commented (Britain and the Arabs [1959]) on how, during the 1914-18 war, `Nobody had time to call for statistics or read up reports or travellers` accounts of Palestine. The fact that there were Arabs living there passed almost unnoticed`. Arthur Balfour did take notice, but discounted it: `Zionist aspirations in Palestine`, he wrote to his government colleague Lord Curzon in 1919, were `of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land`. As for any future political settlement, Britain did `not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country` – telling Lloyd George that in the event of any such democratic deference they `would unquestionably give an anti-Jewish verdict`. Arab hostility to British policy, Balfour insisted in another context, was `almost fantastic in its extravagance` given that Britain had liberated the Palestinians from `a brutal conqueror` and was now only requiring them to give over a `small notch` of territory to people who had for centuries `been separated from it`. Another member of the War Cabinet, and co-drafter of the Declaration, Alfred Milner, shared the dismissiveness: Palestine`s future could not `possibly be left to be determined by the temporary impressions and feelings of the present Arab majority in the country of the present day` [all emphases added]. Sir John Shuckburgh, head mandarin at the Colonial Office, was even more derisory: `the time has come`, he pronounced, concerning Palestine Arabs, in November 1921, `to leave off arguing and announce plainly and authoritatively what we propose to do. Being Orientals, they will understand an order`.

In his Oxford Ford Lecture of 1974 (published in The Decline, Revival and Fall of the British Empire [1982]), John Gallagher observed that just `as care for the security of the Indian empire had led to the creation of an East African empire, so now [post-World War One] the renewed search for the safety of the Raj was building another empire in the Middle East….Here was an elaborate recasting of the Middle East, primarily for external reasons of Indian security.` Barbara Tuchman has written (Bible and Sword [1982]) of Palestine`s special vulnerability in consequence of its `fatal geography`, lying as close as it did to the exposed eastern flank of the vital Suez waterway. In Elizabeth Monroe`s words (Britain`s Moment in the Middle East [1963]), Palestine `was part of the hallowed area round the Suez Canal` – `the wasp waist of our Empire`, as the author of the Declaration himself described it (the Canal cutting the length of the sea journey between London and Bombay by some 40 per cent). The irony, Gallagher suggested, was that at that very time `internal security inside India was failing. It is like a householder seeking fire insurance while his house is beginning to burn down`. A possible double folly, therefore: Palestine acquired for essentially non-Palestine reasons; and these factors themselves now losing their compelling rationale.

Imperial nerves were regularly jangled in the Middle East in the years before the war. Germany, new to the imperialist game, and ruled by the capricious Wilhelm II, had provoked alarm by its ambitious, Suez-avoiding, Berlin-to- Baghdad railway (Bagdadbahn) project, the company set up in 1903 to extend German-financed south-east European and Anatolian lines all the way by land to the Persian Gulf, thereby connecting by sea to India. There was some eagerness, moreover, to stir Jihadi unrest among Britain`s 100-million-odd Muslim subjects across Asia and beyond (attracting the lively attention of the novelist-intelligence chief John Buchan, notably in Greenmantle [1916]: `the last dream Germany will part with is the control of the Near East….Germany`s like a scorpion: her sting`s in her tail, and that tail stretches way down into Asia`).

Kaiser Wilhelm, abandoning Bismarck`s realpolitik focus on strictly European affairs, pursued wider aspirations of weltpolitik, focusing in particular on the Near East, allying himself with the `Bloody Sultan` Abdul Hamid and visiting him in Constantinople in 1889, travelling through the Levant in 1898 and entering Jerusalem on horseback, conqueror-style, in Prussian military uniform. `Thus`, writes Sean McMeekin (The Berlin-Baghdad Express [2010])`was born Hajji Wilhelm, the mythical Muslim Emperor of Germany` Following his tour, `rumours of the Kaiser`s conversion to Islam spread widely throughout the bazaars of the Middle East`. Abdul Hamid`s particular `brand of resurgent Islam`, McMeekin suggests, `had great potential from the German perspective, for stirring up seditious sentiments among the Muslim subjects of Britain and France. Pan-Islam, spreading eastwards on the Baghdad railway, could be Germany`s ticket to world power` – this Islamic revivalism `veering dangerously close to the great imperial choke point at the Suez Canal`. Writing in 1909 (The Short Cut to India), David Fraser conveyed the heady expectations – and, for the British, apprehension – attending the railroad`s construction. `The maker of the line is German; by its means Germany is to colonise Asia Minor, reduce Turkey to vassalage, absorb Mesopotamia, oust Great Britain from the Persian Gulf, and finally to extend the mailed fist toward India`.

Construction impeded at the Taurus mountain barrier in southern Turkey, with the whole thrust of the project weakened politically by the overthrow of the Sultan by the Young Turks in 1908, the railway failed to reach its intended destination before the War, only reaching Baghdad in 1925, later extending to Basra and the Gulf. The Germans and their Ottoman allies, however, had together manifested hostile, provocative, anti-British ambitions for the Middle East and beyond, as such doing more than any other major powers to alert Britain to her Eastern vulnerabilities.

On the eve of the First World War, India provided the United Kingdom with its principal overseas commodity market, most notably for cotton textiles and capital goods.

German-trained Turkish forces had also caused concern by marching from southern Palestine, still under their control, across the open spaces of Sinai to attack the Suez lifeline – albeit unsuccessfully – in February 1915 and May 1916. British commanders and politicians alike agreed that the best guarantee for Suez and, therefore, Indian security now lay in pre-emptive strikes to the east across Sinai in order to block further assaults; to seize from the Turks their departure base in the Judean hills around Beersheba; and to secure the territory in advance of any French moves south from Syria. And so the British entered Palestine.

B. India: The Critical Context

The importance of India as the key referent for Palestine, by way of Suez, lies principally, but not exclusively, in material factors, these placing the sub- continent at the very heart of British commercial and financial self-valuation.

On the eve of the First World War, India provided the United Kingdom with its principal overseas commodity market, most notably for cotton textiles and capital goods, the value of exports there amounting to $344 million in 1913 – 13 per cent of the national total: ahead of the high-income markets of Germany, France, and the United States. No other advanced economy depended so heavily on the underdeveloped world – though it was barely recognised at the time that such orientation towards low-income consumers held little promise for the long-term economic future. Britain was merely replicating, with cottons, the trade that India itself had once dominated and could in time hope to revive with improved productive capacity and the assistance of the international trading structure British merchants were then developing – most notably in the farther East.

Although also a major source of raw materials and foodstuffs, the sub- continent was considerably less consequential as an exporter to the United Kingdom, the result being a large, long-running balance of trade surplus for the metropolitan economy. This combined with returns from massive and unusually secure government and railway investments – returns paid, critically, in sterling against a falling rupee – provided Britain with a payments surplus on its foreign accounts capacious enough in the immediate pre-war period to cover almost 40 per cent of the deficits accumulating in its dealings with increasingly competitive parts of the industrialising world. `India`, argues S.B. Saul in his indispensable study of British overseas dealings (Studies in British Overseas Trade, 1870-1914 [1960]) `was the key to the pattern of world multilateral settlements` – a system of `immense` value to the home economy.

It is important to stress that imperialism, rather than representing a positive exercise for securing added power abroad, was, more commonly, a negative, defensive, reflexive response to seeming threats to existing power.

Additionally, and of the greatest physical and psychological significance, India provided Britain with the world`s largest standing army, for employment not only in the sub-continent but in any part of the globe where British interests seemed under threat (as in Mesopotamia, where tens of thousands were engaged in bitter fighting against the Ottomans in 1917 – and, by telling circularity, in Palestine itself). On the eve of the war, the army comprised 193,901 Indians, 76,953 British, and 45,660 non-combatants – 316,514 in all:`this huge pivotal force`, in Elizabeth Monroe`s words. Beyond all this, it offered that vaporous necessity for a great power – the self-serving semblance of intimidatory authority around the globe. And such strength was available at no direct cost to the British taxpayer, the Indian population paying for its own military and commercial subservience through land taxes and customs & railway charges. Indian taxpayers were further obliged, as Neil Charlesworth shows (British Rule and the Indian Economy 1800-1914 [1982]), to meet `all administrative expenses incurred within Britain as well as in India, paying, for example, the wages of the charladies who cleaned the corridors of the India Office in London`. It was, in sum, the best formalised imperial deal of all time, both the realities and the myths of the Raj taking a firm hold on the ruminations of the British official mind as the Victorian and Edwardian years progressed.

It is important to stress that imperialism, rather than representing a positive exercise for securing added power abroad, was, more commonly, a negative, defensive, reflexive response to seeming threats to existing power – a sort of `protective imperialism` – combining its own ill-considered and short-term rationality with, as suggested above, an often minimal awareness of the specifics of the new territories being annexed. Contemporary theories of imperialism – by Hobson, Lenin, and Schumpeter – convey a sense of metropolitan crisis, of things gone wrong in relations with the so-called periphery.

C. The Imperial Mind: India, Suez, and Palestine

On general imperialist motivation, the prime minister, Lloyd George, `would`, by Michael J. Fry`s account (1977), `match the likes of Milner and Curzon…in their devotion to the Empire and its security`. As for Palestine specifically, imperial issues for him took precedence over Zionism: `Lloyd George would in fact seek Britain`s advantage and God`s purpose, in that order`. On these prime-ministerial priorities, Jon Kimche (1968) notes that `for the moment…it was the British Empire that needed help more urgently than did the Jews`. C.P. Scott records Lloyd George declaring in April 1917 that Palestine was the one` interesting` part of the war – and when earlier asked by the Liberal chief whip, Neil Primrose, `What about Palestine?`, he replied: `Oh we must grab that`. There was no mention of a Jewish national home.

Arthur Balfour, his promotion of Zionism notwithstanding, recorded some bewilderment in 1918 as to the imperial logic determining British policy abroad. `Every time I come to a discussion – at intervals of, say, five years – I find there is a new sphere which we have got to guard which is supposed to guard the gateways of India. These gateways are getting farther and farther from India, and I do not know how far west they are going to be brought`. An obvious part-answer was one he chose not to specify.

There was much clarity, however, in governmental and official appraisals of Palestine`s strategic importance. Lord Curzon, lord president of the council in the War Cabinet, and past viceroy of India, chaired an April 1917 governmental sub-committee on `the territorial desiderata in Asia`, arguing in his subsequent report that `it was of great importance` that `Palestine…should be under British control` and declaring by annotation to a further paper of late 1918:`Palestine is really part of Egypt….Strategically, Palestine is buffer to Suez Canal`. In June 1920, now foreign secretary, he explained to the House of Lords that `we went there…for distinct military and strategic objectives – namely to protect the flank of Egypt, which was threatened by the direct menace of the Turkish arms.` It was `on military grounds that we found ourselves advancing into the Holy Land` [emphasis added]. As for the Middle East generally, if it was asked `why should Great Britain push herself out in these directions? Of course, the answer is obvious – India`.

It was one of the oldest rules in the imperial playbook: retain or acquire a piece of territory whatever its intrinsic value lest others of dubious intent move in with their own forces.

Some weeks later Andrew Bonar Law, chancellor of the exchequer, speaking of the invasion of Palestine, explained to the House of Commons that it would be `a great mistake to suppose that the value of that operation is purely political or moral. That is very far from being the case….We are a great Eastern Power, and anyone who regards the situation at all closely will realise that the view which is taken of our position in India is itself not merely a question of moral [sic] or prestige, but is also a question of our strength in India`. From`the military point of view, then let the House consider what our position in the East would have been today if after we had been compelled to abandon the Dardanelles Expedition…we had left the position in Palestine as it was`. Military operations there and in Mesopotamia had `permanently relieved all danger of attack on Egypt` – and, therefore, Suez. The Balfour pledge was not mentioned.

Two other members of the War Cabinet, Alfred Milner and Jan Smuts, shared the same perspective, Milner, latterly war secretary and colonial secretary, declaring as early as 1915 that the strategic case for taking Palestine from the Turks was `most persuasive`, and Smuts, in 1917, viewing such annexation as a matter of imperial necessity, any other power in control there being likely to constitute a `serious menace`. Winston Churchill, Milner`s successor as colonial secretary, told the Commons in July 1922 that Palestine was presently`all the more important to us…in view of the ever-growing significance of the Suez Canal`. Regarding military spending (then under debate) he did `not think £1,000,000 a year [around £50,000,000 in present money]…would be too much to pay for the control and guardianship of this great historic land`.

Such strategic evaluations were especially important in the early 1920s following Lloyd George`s replacement, in October 1922, by a Conservative administration, uneasy over Zionist commitments but open, if warily, to the imperial arguments of its predecessor – as well as to notions of policy continuity. In the words of Arthur Balfour`s cousin and lord president of the council, the marquess of Salisbury (son of the imperialist prime minister) `the [Palestine] policy with which we are dealing tonight [Lords debate, 1 March 1923] is not the policy of the present Government. It is the policy of the late Government, to which we have succeeded….It cannot altogether be done, but to some extent we must pay regard to it, because the honour of this country and its consistency is engaged`. But as for Zionism specifically, the colonial secretary, the duke of Devonshire, was fully alert to the problematical`injustice of imposing upon a country a policy to which the great majority of its inhabitants are opposed` [emphasis added].

Devonshire`s office head, Sir John Shuckburgh, also held to the strictly annexationist perspective. He was concerned about the implications for Suez of the granting of qualified independence to Egypt in 1922. This could`seriously affect our hold upon the Suez Canal` – any adverse future circumstances in the region meaning that `the control of Palestine might be of vital importance to us`. He signalled his agreement with Sir Gilbert Clayton, civil secretary of Palestine, 1922-25, who had argued `that the retention of British control in Palestine is essential from the standpoint of Imperial strategy`. Turkish-German attacks on Suez during the war, Clayton argued, had shown that `the waterless regions of Sinai` were no longer an effective `barrier against hostile advance` – meaning that it was now `necessary to advance the line of the defence of the Canal by many miles`. The recent accommodation of Egyptian nationalism further showed that `the march of events has shifted the key to our Eastern communications by sea and air from Egypt to Palestine` (emphasis added). The Times offered a similar, if complacent, observation in November 1922: `it is, to put it no higher`, given Egyptian uncertainties, `wise strategy to have in Palestine a state [sic] that owes us thanks for its birth and early development`.

An 11-man Cabinet Committee set up in 1923 by Stanley Baldwin, now prime minister, to review Palestine policy was also in agreement with Clayton, reporting in July that it was a matter of `the most urgent need` that the Palestine mandate be decisively and finally confirmed.` Any withdrawal there would mean the strong possibility of either France or Italy taking charge in a manner likely to be `injurious to British … interests`; or, failing that, and with the resident Arab population left to its own devices, of a `disastrous` return by Turkey to retrieve its old domains, thereby making nonsense of all Britain`s war efforts in the Levant. Given `the strategical value` of the territory, `none of us` on the Committee `could contemplate with equanimity the installation in Palestine of another Power`. The cabinet promptly approved the report.

It was one of the oldest rules in the imperial playbook: retain or acquire a piece of territory whatever its intrinsic value lest others of dubious intent move in with their own forces. For Curzon, in his last months, and still foreign secretary, the special worry was the French – perhaps tempted, as he saw it, to attach any vacant Palestine to their adjoining Syria Mandate. Once again, Zionism was not mentioned. The stakes were much higher than those raised by the sponsorship of Jewish settlement – apart that is from its implied bearing on British `consistency`. Nothing `could be worse`, declared Lord Salisbury, than the government appearing to be `a zig-zag administration`. It was an elementary question of reputation. And so the Balfour commitment persisted within the imperial frame – but with no attendant enthusiasm whatsoever.

D. `Strategical Zionism` and `The Seventh Dominion`

Given London`s preoccupation with Palestine`s seeming strategic value rather than as a Jewish homeland, it is unsurprising that Zionists and their supporters picked up the imperial argument to advance their special cause. If the British could not guarantee a convinced and convincing long-term commitment to Zionism, then the movement`s advocates could at least take a knowing ride on the imperialist war horse . It was only at this point that the Zionist and imperial objectives seemed to fuse – but fallaciously so.

Winston Churchill speculated back in 1908 that the `establishment of a strong, free Jewish State [sic] astride the bridge between Europe and Africa, flanking the lands to the East, would … be an immense advantage to the British Empire`- Jews, presumably, being more trustworthy than Arabs as promoters of British interests. He was of the same mind in 1920: a future `Jewish state [sic] under the protection of the British Crown…would be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire`. Quite how this would work out in practice he did not say. It was a casual race-infused assumption.

Leo Amery, in Lloyd George`s Cabinet Secretariat during the war, was a little more specific, foreseeing a sentimental dividend. Zionism was a means of `establishing in Palestine a prosperous community bound to Britain by ties of gratitude and interest` – Jews, by another racist trope, also guaranteeing economic success by their supposed commercial acumen. He offered no evidence, however, as to the transferability of such virtue from the ghettoes of eastern Europe to the barren lands of Palestine. In similar vein Alfred Milner`s private secretary, William Ormsby-Gore, hailed the Jews in 1917 `as the one sound, firmly pro-British constructive element in the whole show`. Their function essentially was to be servants of empire; and if they were to bring in some of their assumed wealth, so much the better.

Christopher Sykes (son of Sir Mark) notably advanced the concept of `strategical Zionism` – imperial interests being served by the introduction of a European settler community into Arab Palestine. The journalist Herbert Sidebotham had a similar idea: `a Great Dominion of Jews` – people `at the same stage of development as ourselves`, and `as such not a burden, but an increment of strength`. Quite how the Jews would measure up to this role or resident Arabs fit into the racial polity was not considered. As with all supposedly inferior peoples, theirs was not to reason why. The Labour M.P. Josiah Wedgwood advanced yet another version of the same in the title of his book, The Seventh Dominion (1928), Jews to be given that imperial status within the broader empire. `Palestine is emphatically a place where we do want a friendly and efficient population – men on whom we can depend`. Even Sir Edmund Allenby, the conqueror of Palestine and one-time opponent of Zionism, came to believe by the early 1920s that the territory could hold major value for wider British interests

Appreciation was what Herbert Samuel, the first British high commissioner, expected, suggesting in 1917 before his appointment, that the best safeguard against any `menace` to Palestine, French or otherwise, would be the establishment there of `a large Jewish population, preferably under British protection`, such – as with Amery – being `calculated to win for the British Empire the gratitude of Jews throughout the world, and create among them a bias favourable to the Empire`. Again, the condescending notion of Jewish moral indebtedness, willingly accepted. At the Foreign Office, Hugh O`Beirne, former United Kingdom representative in Petrograd and Sofia, saw it rather more as a hard-nosed deal: Britain did not `propose to give the Jews a privileged position in Palestine for nothing but…we should expect wholehearted support from them in return`. They should be allowed to grow `strong enough to cope [sic] with the Arab population`, enabling Britain `to strike a bargain for Jewish support`.

One has to wonder if many in official circles were doing serious, informed thinking on these matters, as distinct from formulating abbreviated, lazy, derivative rhetoric about people, east European Jews as well as Levantine Arabs, about whom they knew, or chose to know, very little – apart from the inchoate assumption that in their tight little west-Asian locale they might together have some loose bearing on the security of the Raj. The imperial mind seems to have been approaching some degree of intellectual saturation given the scale and spread of the issues with which post-war officialdom was having to engage, the British empire being then not only at the very acme of its physical spread, but also, post-War, at its most vulnerable.

Zionists themselves, uncertain as to Britain`s enduring commitment to their cause, decided it might make political sense to take their cue from the welter of imperialist `reasoning`. Chaim Weizmann, writing to the journalist C.P. Scott in the early months of the war, referred to prospective Jewish settlers as being `a very effective guard for the Suez Canal`. Weizmann was always keen, Avi Shlaim suggests (2004), to hitch `a lift with the British Empire`. His English friend Israel Sieff recorded later (1970) that Weizmann`s conviction on the matter was in fact genuine rather than merely tactical; they both confidently `believed that a Jewish Palestine would become a bastion, firmly held in the course of time, by hardworking, skilful, devoted and loyal people, which would stand guard over the greatest sea and land routes linking the three continents`. Again, mere pious, racially implicit rhetoric, lacking any specificity on modes of guardianship.

The ageing French-Hungarian Zionist, Max Nordau, co-founder with Theodor Herzl of the World Zionist Organisation in 1897, repeated the same loose notion in an address to an Albert Hall audience in 1919 that included Lloyd George and Balfour: `We shall have to be the guardian of the Suez Canal. We shall have to be the sentinels of your way to India via the Near East [emphasis added]. For the Anglo-Jewish writer Israel Zangwill, a Zionist Palestine would serve as an `Asiatic Belgium …separating the Suez Canal` from any outside hostile forces. Herzl himself, back at the turn of the century, had written to the then foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, arguing that any concession, anywhere, of land for Jewish colonisation would mean that `at one stroke England will get ten million secret but loyal subjects active in all walks of life…all over the world`.

Weizmann had consistently told his fellow Zionists that their entire scheme would prove a hopeless quest without the force majeure of a `mighty and great power`; thus the insistent need to persuade the United Kingdom of the strategic value of Zionist settlement. Zionism, he knew, could only advance territorially if developing an intimate connection with the British Empire – or, at least, if British statesmen could be persuaded that such a relationship might be to their own imperial advantage. It was not a particularly difficult argument to advance in the nervous, expansionist climate of the times.

Part Two: British Palestine and `The March of Folly`

A. Contemporary Anxieties

`World systems`, writes John Gallagher, `are always insecure`. By that token one might assume the larger the spread the greater the insecurity. At the centre of the improbably far-flung British system – at its widest-ever after the War and now including Palestine – lay the Raj. The territorially licentious mindset of the times is exemplified by Sir Alfred Lyall in the 1919 edition of his book, The Rise and Expansion of the British Dominion in India. Lyall, sometime poet, biographer, and university lecturer, was no crude jingoist. He did, however, reveal the extravagances of the anxious India-focussed mind – his experience there dating back to the Mutiny/Great Rebellion of 1857 and his positions of authority including the lieutenant-governorship of North West Provinces & Oudh and membership of the secretary of state`s Council of India in London. Concerning the imperial predicament, however, he wrote with alarm – echoing Balfour – how nothing could `illustrate more signally the radical and inherent mutability, the accidental and elastic character, of all territorial settlements in Asia, than the fact that at this moment our statesmen are still in quest of that promised border-land whose margin seems to fade for ever as we follow it`.

The British, Lyall explained, had made clear `our determination to permit no encroachment of another European power upon the vast tracts of mountains and desert that stretch from the Himalayas northward to the confines of Mongolia. Our policy is to keep clear of intrusion all the approaches to India, and to hold in our hands the keys of all its gates [emphasis added]. Upon this system we have been obliged to multiply and throw forward our military outposts, and accept a great augmentation of sundry and manifold political responsibilities. The outer frontier of the British dominion that our policy now requires us to defend, has an immense circumference`. By such measure, Palestine counted as little more than a minor war trophy picked up along the highway to India.

Barbara Tuchman, in the wide-ranging study (The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam [1990 edn.]) that gives its title to this section, cites three criteria for `Folly`s` possible relevance to such governmental affairs, two of which state that `the policy adopted … must have been perceived as counter-productive in its own time`, and that `a feasible alternative course of action must have been available` . Palestine most certainly fits the former in the sense that the annexation and accompanying Zionist programme produced noisy choruses of alarm in the United Kingdom and in Palestine itself; and the second as well, considering that the British could not only have diluted their sponsorship of Zionism but also held back from annexation in favour of some peace deal with their one-time Ottoman allies – and generally sobering up on their India inebriation. There was much talk in 1918, and some thinking on Lloyd George`s part – when the Germans were in War-time ascendancy, lasting until the early autumn – of arranging a settlement with Turkey under which Palestine would be handed back to Constantinople. And if the territory was retained, Zionism could, Joseph Jeffries held, be promoted in strictly religious and cultural terms, avoiding all entangling commitments of a political nature.

It is the first of these Tuchman criteria that will be considered here for the six- plus years between the Declaration of November 1917 and the final Mandate settlement of July 1924. The second is essentially counter-factual, with the number of practicable variants registering as infinite. And our focus, it must be stressed, lies squarely on British policies as they affected British interests, and only on the Arab predicament as it affected these interests. The tragedy for the Arab communities needs a much stronger term than `folly`.

A great number of informed and concerned individuals pronounced unambiguously on the foolishness of the annexation and national-home plan well in advance of 1924, insisting that the policies would inevitably be, in Tuchman`s term, `counter-productive` for Britain as an Asian power. In the very month of the Declaration, Gertrude Bell, then oriental secretary to the British governor of Baghdad, expressed alarm in a letter to her parents: `I hate Mr Balfour`s pronouncement….To my mind it`s a wholly artificial scheme divorced from all relation to facts and I wish it the ill success that it deserves`. It was, she later suggested, `like a nightmare in which you foresee all the horrible things that are going to happen and can`t stretch out your hand to prevent them`.

The policy, however, was not discussed in Parliament; and such was the nervousness over its reception in Palestine that the British authorities in Cairo headquarters were instructed in 1919 to treat the Declaration as `extremely confidential, and on no account for any kind of publication` (which did in fact follow in May 1920). In government, Lord Curzon suggested in a much-quoted document of October 1917 that the Arabs `whose forefathers have occupied the country for the best part of 1,500 years` would not `be content either to be expropriated or to act merely as hewers of wood and drawers of water` for the incomers. In 1920, with the Declaration now the basis of policy, he hoped at least to `water down the Palestine mandate which I cordially distrust`. Two years later, even Lloyd George – ultimately responsible for the Balfour promise – told the Commons that the sense that `somebody has broken faith with them` was `disturbing the Arabs throughout the whole of this great area….The Arab race, its pride, its sense of justice and fair play has been outraged by the feeling that somehow or other things have not quite been done in the way they had expected` [emphasis added]. Sir Ronald Storrs, military governor of Jerusalem, did not share the feigned surprise: Arabs in Palestine seeking political justice had `about as much chance as had the Dervishes before Kitchener`s machine guns at Omdurman`.

Captain C.D. Brunton of intelligence services in Jerusalem reported to London, 13 May 1921, that `the Arab population here has come to regard the Zionists with hatred and the British with resentment` – the situation notably aggravated, he suggested, by Winston Churchill`s recent visit to Palestine as colonial secretary, when he managed to `put the final touch to the picture. He upheld the Zionist cause and treated the Arab demands like those of negligible opposition to be put off by a few polite phrases and treated like children`.

Some months later the same Churchill commented in a memo that Arabs and Jews were `ready to spring at each others` throats`. The former, showing `irritation, suspicion and disquietude`, were aware that the manner of British rule stood in contradiction to `our regular policy of consulting the wishes of the people in mandate territories`. A memo circulated by his office, June 1921, pointed out that the government was `following a policy which is unpopular with the people of the country`: it was now `almost universally recognised that the mandate cannot be maintained in its present form`.

The policy, however, was not discussed in Parliament; and such was the nervousness over its reception in Palestine that the British authorities in Cairo headquarters were instructed in 1919 to treat the Declaration as `extremely confidential, and on no account for any kind of publication’.

And almost the entire British civilian and military leadership in Palestine was volubly critical, General Sir Arthur Money, head of the immediate post-war administration, declaring in 1919 that `even a moderate Zionist programme can only be carried through by force in opposition to the will of the majority of the population`. Further official worries were triggered by riots in Jerusalem and Jaffa, these leading to the appointment of two commissions of inquiry headed by Major-General Sir Philip Palin, 1920, and Sir Thomas Haycraft, 1921. Palin`s conclusions were stark: `the native population, disappointed of their hopes, panic-stricken as to their future, exasperated beyond endurance by the aggressive attitudes of the Zionists, and despairing of redress at the hands of the Administration which seems to them powerless before the Zionist organisation, lies a ready prey for any form of agitation hostile to the British Government and the Jews`. Haycraft reported a range of basic Arab grievances `too genuine, too widespread, and too intense` to be disregarded, setting out as an example of Jewish provocation the evidence submitted to his body by the head of the Zionist Commission, Dr. David Eder, that `there can only be one National Home in Palestine, and that a Jewish one, and no equality in the partnership between Jews and Arabs, but a Jewish preponderance as soon as the numbers of the race are sufficiently increased [emphasis added]. It had been a Jewish assumption, commented Sir Ronald Storrs, that they would `have the new dish of freedom served up to them on a nice gold salver…while the Arabs waited gracefully at the table`.

The last head of the military establishment in Jerusalem (and previously General Allenby`s chief of staff ) Sir Louis Bols, complained to London in 1919 that Zionist leaders like Eder were flagrantly bypassing his authority: `this state of affairs cannot continue without grave damage to public peace and to the prejudice of my Administration….It is manifestly impossible to please partisans who officially claim nothing more than a “National Home”, but in reality will be satisfied with nothing less than a Jewish State and all that it politically implies`. There was an assumption that `in any question in which a Jew is interested discrimination shall be shown in his favour`. Richard Meinertzhagen, appointed Allenby`s chief political officer that same year and, as a self-described `ardent Zionist`, no friend of the Arabs, warned in 1922 that their leaders, recently bidding for political justice in London, `will return to Palestine with failure thrown in their faces and will assuredly not let the matter rest there. Arab mentality … will absorb the lessons of Ireland and Egypt. The extraneous toxin which has hitherto characterised Arab agitation against Zionism will continue to work on the Arab mind`.

This `Arab mentality` was held in aggressively low esteem by most of the Zionist leadership – not excluding Chaim Weizmann. The British themselves, John Marlowe observes (The Seat of Pilate [1959]), took an essentially colonialist view of the Arab population. `The possibility or the desirability of Arab-Jewish co-operation on equal terms…never seems to have been envisaged by H.M.G.` who `appeared to assume the same pattern of “white” colonisation as existed in East Africa and Rhodesia`. Weizmann, however, still found cause for complaint, writing from Tel Aviv in a long letter to Arthur Balfour, 30 May 1918, (Papers and Letters [1977]) that the British authorities in Palestine were being unduly fretful over local sensitivities, fearing `the treacherous nature of the Arab` who, `superficially clever and quick-witted…screams as often as he can and blackmails as much as he can`. Dominating the lower levels of the new administration, the Arab showed himself to be `corrupt, inefficient, regretting the good old times when baksheesh was the only means by which matters administrative could be settled`. Any attempt to show justice towards his community was `simply interpreted as weakness…The fairer the English regime tries to be, the more arrogant the Arab becomes`. The British in their foolishness were `not conversant with the subtleties and subterfuges of the Oriental mind. So the English are “run “ by the Arabs`, whose typical leader was `dishonest, uneducated, greedy, and as unpatriotic as he is inefficient` – such character standing in sharp contrast to the `conscious and considered` practices of `the majority of the Jewish people`, sturdy in their loyalty to their British rulers.

What is remarkable about this savage judgement is that it was delivered by the leading Zionist himself, who knew all about demeaning tropes – and that it was offered unqualified to the British foreign secretary, who one might expect, official bias aside, to have been looking for reassurances that the emerging polity could be ethnically harmonious and stable enough to defend wider British imperial interests. And Weizmann presumably knew from prior contacts that the crudity of his views would not be in any way troubling for Balfour – who, to add to the moral mayhem, could himself furnish a few anti- Jewish tropes, writing in 1919 about `the age-long miseries created for Western civilisation by the presence in its midst of a Body (sic) which it too long regarded as alien and hostile, but which it was equally unable to expel or to absorb`.

In early 1923 the Daily Mail added to the dispiriting forecasts, presenting more than two dozen articles by the Anglo-Irish journalist Joseph Jeffries, a former Middle East war correspondent, under the telling general title of The Palestine Deception (published in book form, Institute of Palestine Studies, Washington D.C., 2014) which ridiculed London`s efforts `to establish in a strategic corner in the Near East a body of people in close coalition with the British`. Jeffries provided chapter and verse to demonstrate, for the first time to a British readership, that the government had casually and provocatively betrayed the previous promises that they, through the person of their Cairo representative Sir Henry McMahon, had made to Emir Hussein and the Arabs, to the effect that they would be granted their own independent state after the war (articles of 11 and 12 January headed, respectively, `Misleading the Arabs` and `Broken Faith with the Arabs`). Chairing a meeting of the Cabinet`s Eastern Committee a year after the Declaration, with Balfour and T.E. Lawrence in the room, Lord Curzon reminded his colleagues of `our commitments` to Hussein of October 1915, `under which Palestine was included in the areas as to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future`.

The Mail`s editorial of 9 February 1923, after Jeffries, argued that `we ought to evacuate Palestine at once and not remain there. We ought, that is to say, to fulfil our first and earliest promises to the Arabs who are seven-eighths of the population of Palestine, and give them independence, instead of trying to force on them with our aircraft and bayonets the rule of a mere fraction of Zionists`.

British as well as Arab interests were at stake: `If we persist in this policy, then it may be predicted with certainty that nothing but embarrassment and ruinous expenditure await us in Western Asia.`

The Jeffries articles had an immediate energising effect in Parliament, the House of Lords putting aside a number of days in early 1923 for debating Palestine policy. Prominent in the exchanges were three recent imperial governors: Lords Lamington (Bombay 1903-07), Sydenham (Victoria 1901-03, Bombay 1907-12), and Islington (New Zealand 1910-12), all of whom had previously been party in June 1922 to a Lords call for radical revisions to the intended Mandate, and carrying their motion by a wide margin of 60 to 29 (with Arthur, now Lord, Balfour in dismayed attendance). Lamington, declaring himself to be a past supporter of the national home idea, observed how on a recent visit to Palestine he had had to acknowledge `the absolute impossibility` of its realisation `except with the protection of our troops`. In June, Viscount [Edward] Grey of Falloden, the former foreign secretary, set out his conviction that arguments for continuity, dating back to the Declaration, were now `against the public interest`. He could not `think of any instance where adherence to policy will be to a greater and graver degree opposed to the Imperial interest than the continuance of the policy as laid down and prescribed at the present moment in Palestine` [emphasis added].

Zionism did not sit at all comfortably with Britain’s Muslim responsibilities, most particularly in India.

B. Ethnic Questions

This great spread of acutely apprehensive opinion in the years running up to the Mandate`s final settlement was not remotely balanced by more optimistic assessments. The notion of possible compensatory benefits – that Jews would at least be able to perform as `guardians` and `sentinels` of the Suez Canal – was impossible to sustain, given that the bird-fly distance between Jerusalem and Suez across the desert wastes of Sinai was in excess of 200 miles and that there was no plan, fanciful or otherwise, to set up defensive Jewish guard- posts between Palestine and the waterway. The emerging polity overall could not by itself help protect the Canal by military or other means, being manifestly unstable from its very first days, with Muslim and Jewish communities suspicious the one of the other and regularly engaged in localised physical conflict. British energies were employed much more with the persistent political mayhem than with any defending of the far-distant Raj.

Issues `arising from Zionism in Palestine extend far beyond the geographical limits of the territory of Palestine`, Lord Islington suggested in one of the Lords exchanges in 1923. `The effect upon the whole Arab and Muslim world to-day Is a most unfortunate one. It has infected large masses of that world with discontent and indignation`. In 1921 Muslims accounted for nearly 70 million souls in the sub-continent – almost a quarter of the India population. And Suez itself, of course, was squarely located in Islamic territory. `Britain`, writes Jonathan Schneer (The Balfour Declaration [2010]), `…ruled over a Muslim empire whose main outposts were in South Asia, Egypt, and Sudan` – numbering close to a hundred million people. And, as has been noted, it was Germany`s particular hope that if Jihadi revolts could be energised in these Islamic communities, the entire British imperial edifice in the East might begin to crumble.

Zionism did not sit at all comfortably with Britain`s Muslim responsibilities, most particularly in India. There were elements in the Ottoman leadership, writes Schneer, who wished for `a compromise peace with the Allies` – to a degree reciprocated – but adamantly opposed by British Zionists. Lloyd George himself `could not get the possibility of a separate peace with Turkey out of his head. That such a peace might jeopardise the possibility of a British protectorate in Palestine, which he was simultaneously encouraging Zionists to anticipate, apparently did not matter to him`.

Herein lies further evidence of fracture in governmental reasoning, brought on – if one judges empathetically – by the short-term pressures of war, with its constantly fluctuating fortunes and sudden shifts in geographical and strategic focus, these inevitably causing confusion among those, at home and abroad, taking responsibility for the impossibly wide span of British imperial governance.

And what too of the predicted loyalty of Jewish immigrants to the British crown and its purposes? Ronald Storrs wrote that the large numbers coming in from Russia carried a powerful `Kultur` with them, involving a `deep-seated intellectual contempt of the Slav for the Briton`. The idea that a Zionist Palestine would become, in Joseph Jeffries` phrase, `a limb or defence of the British Empire`, was one he held to be `Preposterous nonsense. In the 9 months up to June last year there were 63 British immigrants out of 7,051: 6,220 were from Poland, Ukraine, Russia, etc. The majority are only interested in Hebraicism. Active non-British elements are amid them`. Such east European Jews were more likely to emerge as a threat to imperial interests then to perform as the `little loyal Jewish Ulster` of British imagining. `The new groupings in Palestine are Judaeo-Slav; their attitude upon life is Judaeo-Slav; their mental intoxication is Judaeo-Slav; and, should the present regime continue … all points to a State not protective but perilous to Egypt, to the Near East, and to British communications`.

C. The Fading Jewel

Finally: what degree of folly attaches to the focus on India as the paramount international concern of policy-makers? John Gallagher was cited at the outset observing that while India was continuing to transfix the British official mind, its `internal security was fading. It is like a householder seeking fire insurance while his house is beginning to burn down`. There was, however, a lot of destruction to be completed, and there appeared every sign after the War that the structure could stand for a good many years to come. Folly between the Declaration and the final Mandate lay less in any exaggerated appraisal of the sub-continent`s economic and military value than in the idea that a small, far-distant Levantine territory, destabilised by the Balfour policy, could, as `guardian` or `sentinel` for Suez, play any significant part in India`s security such as to justify Palestine`s annextion. And yet, as we have documented, that compelling India perspective, rather than Zionism, was the prime reason for its `grab`, by Lloyd George`s expression. Alfred Lyall`s comments, as cited, about seizing all the borderlands of India, show the inflamed imperial compulsions at work by which European rivals had to be kept well away from any territory on the passages to India or adjacent to it.

India was of great and continuing economic value to Britain, and in the uncertainties and instabilities of the post-war years the impulse was to cement rather than to loosen imperial ties. As late as 1938 India still served as Britain`s principal overseas market, taking $196 million worth of the country`s exports; and as an investment field, its share of the country`s overseas holdings stood at 13 per cent by estimated value in the same year. As for military manpower, the United Kingdom was able to count on huge numbers for World War Two, the Indian Army numbering more than 2.5 million by 1945, (with more than 87,000 killed in the hostilities). Arguably, the military contribution registered more in British minds, official and civilian, than did the more arid measures of trade and investment. In his The Rise and Fall of the British Nation [2019]), David Egerton characterises imperial Britain as more `warfare state` than `welfare state`, such being `central to the internal story of the colonial empire – it was kept by force, kept going in part to preserve military bases and lost by an inability to use enough force to keep it`.

It might, however, count as folly that this high degree of economic and military dependence was allowed to continue right up to Indian and Pakistani independence in 1947 – after which the mighty force of 2.5 million evaporated as a British asset, thereby radically altering the whole complex of the country`s overseas relations. Lord Alanbrooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff in World War Two, was clear: `Without the central strategic reserve of Indian troops able to operate either east or west we were left impotent`. Four of the ten Gurkha regiments were transferred to the British army in 1947, the remainder and all other forces being divided between India and Pakistan. It was, as Alanbrooke saw, an enormous blow to Britain`s standing and rationale as an imperial power, not only because of the loss of the military resource that had been used in various corners of the empire (including Suez, Sinai, and Palestine – where lancers from the northern Princely States, notably Mysore and Hyderabad, were famously involved in the capture of the port and railhead of Haifa in September 1918) but because independence itself had removed India and anxieties pertaining thereto as the prime motive and justification for earlier British imperial extensions. It was no mere coincidence that Zionist Palestine detached itself from the empire shortly after. Indian and Pakistani independence came on 15 August 1947; the state of Israel`s nine months later, 14 May 1948.

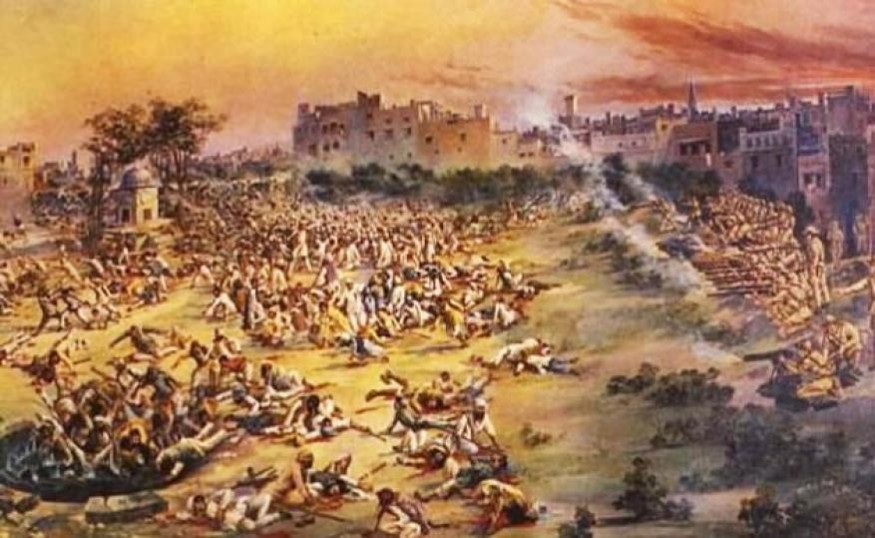

The political ground was ominously shifting, in no small part on account of war itself. India had contributed not only manpower and but also its funding in 1914-18. By Erez Manela`s account (The Wilsonian Moment [2009]) `wartime hardships fostered a general mood of restlessness and anticipation, and this, combined with the tremendous Indian contribution of men and materiel to the war effort, led many Indians to expect Britain to reward them, after the end of the war, with a greater voice in their own government`. Such gratitude, however, was not forthcoming. Sikhs and others returning home found themselves objects of suspicion under the repressive 1919 Rowlatt Act perpetuating War-time press censorship and provisions for imprisonment without trial as a means of suppressing anticipated `political outrage`. Further severe provocation came with the massacre at Amritsar in Punjab, 13 April 1919, when soldiers under the command of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer released without warning 1,650 rounds of ammunition on an unarmed, largely Sikh, crowd of 15-20,000 men, women, and children, celebrating the annual religious festival of Vaisakhi (solar New Year) in the enclosed Jallianwala Bagh, killing 379 by official statistics but multiples of that figure by other counts – an unrepentant Dyer (himself enjoying some empire-hero popularity back in Britain, with Rudyard Kipling contributing to his large support fund) declaring shortly after: `I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed…producing a sufficient moral effect from the military point of view`. This paralleled the sentiment expressed in 1920 by the commander-in-chief of the British army in India, General Henry Rawlinson: `You may say what you like about not holding India by the sword, but you have held it by the sword for 100 years and when you give up the sword you will be turned out`.

Concessions to nationalism in the form of the 1919 Government of India Act, following the Montagu-Chelmsford (India secretary – viceroy) report of the previous year, by only modestly extending the franchise for a limited range of regional-government matters, served more to provoke than to reassure, lending impetus to increasingly vigorous anti-imperial movements led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak up to his death in 1920 and Mohandas Gandhi following his return from South Africa in 1914 – the former, founder of the Home Rule (Swaraj) League in 1911, and much imprisoned by the British; the latter taking over the leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, working with the Muslim Khilafat body, organising his non-cooperation campaign (Satyagraha), and invigorating the existing buy-Indian movement (Swadeshi) which, in turn, was helped by the rise in import tariffs for cottons and other articles, principally for revenue reasons, following the circumstantial protections of war. Charlesworth writes of an `explosion in customs duties` after 1914.

The central reasons for imperial extension in Asia, from Palestine in the west to India`s borderlands in the east, were steadily weakening, and by 1948 had disappeared completely.

D. In Sum

The British, it is obvious, could not have implemented their Balfour Declaration without the concomitant annexation of Palestine, but as the argument here has indicated, that annexation did not take place to assist such implementation. Government ministers like Lord Curzon, Andrew Bonar Law, and many others made it clear in the years leading up to the finalisation of the Mandate in 1924 that the principal drive was imperialist rather than Zionist, relating in the main to the security of the Suez Canal and continuing access to India and the farther East. Knowing this, and in particular when official enthusiasm for Zionism started to wane after Lloyd George lost Office in 1922, proponents of the national home project knowingly used strictly imperial arguments to hold succeeding British governments to the Balfour commitment of 1917 – these arguments centring on India as the prime overseas support of British economic and military power around the world. The folly was to believe that a British Palestine could act as `guard` and `sentinel` for the protection of that vital imperial relationship – and, more generally, that India could continue as such a support for the metropolis into the indefinite future.

The restless concern over India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has to be powerfully emphasised, for it was that set of chronic anxieties that took the British not only into neighbouring territories such as Afghanistan and Burma, as Sir Alfred Lyall explained, but also, by Robinson and Gallagher`s arguments, into vast expanses of northern, eastern, and southern Africa as well. China too was forced into unequal treaties to protect India`s foreign-exchange earning capacity, initially through the opium trade.

Palestine, it is clear from the governmental judgements cited, was carried along in this sweep of protective expansionism – but essentially, by its size and its location, without actual imperial purpose. It featured more as the site of a latter-day, emotionally charged, settler experiment, this introducing chronic social and political instability into a part of the world which, if it was indeed to serve a broader strategic function, should have been a haven of Britain- oriented stability. That was a key dimension of folly, for it was clear, from almost universal contemporary appraisal, that the experiment was bound to fail by any means short of the incomers exercising a form of colonialist control over the residents; and that, in any broader sense, was no sort of success.

George Antonius, acknowledging (The Arab Awakening [1938]) the horror of European persecution of its Jewish populations and of the `sacrifices needed to alleviate suffering and distress`, registered shock at the solution that was in fact being adopted: `To place the burden upon Arab Palestine is a miserable evasion of the duty that lies upon the whole civilised world. It is also morally outrageous. No code of morals can justify the persecution of one people in an attempt to relieve the persecution of another` [emphasis added].

Palestine and India, intimately connected in the minds of British policy-makers in the aftermath of the First World War, progressively, in the inter-war period, drifted steadily apart – the former preoccupied with internal ethnic conflict (witness the bloody inter-communal violence of 1929-30 and the prolonged Arab Revolt of 1936-39) than with any grand imperial strategy; the latter, also looking inward, fixated on the destabilising turmoil accompanying ascendant nationalisms and class & religious conflicts. The global imperatives for Palestine that had seemed so compelling in the years between the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the Mandate settlement of 1924 were now rapidly receding over the eastern horizon.

In 1920, Winston Churchill had held that a future `Jewish state under the protection of the British Crown…would be in the truest interests of the British Empire`. Two decades on, as prime minister, he recognised the folly of such enthusiasm: Palestine had turned out to be a `very difficult place` to govern. `I am not aware of the slightest advantage which has ever accrued to Great Britain from this painful and thankless task`. His successor as premier, Clement Attlee, reflected a few years later, following his own struggle with Palestine impossibilities: `We`d started something in the Jewish National Home after the World War…; it was done in a very thoughtless way … a wild experiment that was bound to cause trouble….The interests of Arab and Jew in Palestine were quite irreconcilable`.

Two of Britain`s most involved statesmen, unambiguous by the 1940s on the country`s profound Levantine folly.

William M Mathew: MA (Glasgow) PhD (LSE) FRHistS, University of East Anglia (previously University of Leicester and University of Missouri St Louis). Books include The House of Gibbs and the Peruvian Guano Monopoly (London, 1981 & [Spanish edn] Lima, 2009); Edmund Ruffin and the Crisis of Slavery in The Old South (Athens GA and London, 1988 & [p’back] 2012); Keiller’s of Dundee: The Rise of the Marmalade Dynasty (Dundee, 1998); (ed) Joseph Jeffries, The Palestine Deception, 1917-1923 (Washington DC, 2014).

Suggested Further Reading

Balfour 1922-23: Fragile commitment and Zionist Response

Rescuing Balfour: Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office 1921-22

Joseph Jeffries and the ‘Palestine Deception’, 1923

Principal Sources

Antonius, George: The Arab Awakening (London, 1938)

Charlesworth, Neil: British Rule and the Indian Economy 1800-1914 (London, 1982)

Edgerton, David: The Rise and Fall of the British Nation. A Twentieth-Century History (London, 2019)

Gallagher, John, ed. Seal, Anil: The Decline, Revival and Fall of the British Empire (Cambridge, 1982)

Glub, Sir John Bagot: Britain and the Arabs. A Study of Fifty Years 1908 to 1958 (London, 1959)

(Hansard) The Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, House of Lords, sundry 1921-24

Ingrams, Doreen (Compiler and Annotator): Palestine Papers 1917-1922. Seeds of Conflict (London etc., 1972)

Jeffries, Joseph: Palestine: The Reality (London, 1939)

Jeffries, Joseph (ed. Mathew, William M.): The Palestine Deception 1915-1923. The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, the Balfour Declaration, and the Jewish National Home (Washington D.C., 2014)

Klieman, Aaron S.: Foundations of British Policy in the Arab World. The Cairo Conference of 1921 (Baltimore, 1970)

Lyall, Sir Alfred: The Rise and Expansion of the British Dominion in India (London, 1919 edn.)

McMeekin, Sean: The Berlin-Baghdad Express. The Ottoman Empire and Germany`s Bid for World Power, 1898-1918 (Penguin, 2010)

Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford, 2009)

Marlowe, John: The Seat of Pilate. An Account of the Palestine Mandate (London, 1959)

Mathew, William M.: `The Balfour Declaration and the Palestine Mandate , 1917-23: British Imperialist Imperatives,` British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (40, 3, July 2013)

Monroe, Elizabeth: Britain`s Moment in the Middle East (Baltimore, 1963)

Newsinger, John: The Blood Never Dried. A People`s History of the British Empire (London, 2006)

Robinson, Ronald & Gallagher, John, with Alice Denny: Africa and the Victorians. The Official Mind of Imperialism (London & Basingstoke, 1961)

Roskill, Stephen: Hankey: Man of Secrets, vol. I, 1877-1918 (London, 1970)

Sanghera, Sathnam: Empireland. How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (Penguin, 2021)

Saul, S.B.: Studies in British Overseas Trade 1870-1914 (Santa Barbara, 1990 edn.)

Schneer, Jonathan: The Balfour Declaration. The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (London etc., 2010)

Tharoor, Shashi: Inglorious Empire. What the British Did to India (Penguin, 2018)

Tuchman, Barbara W.: Bible and Sword. How the British Came to Palestine (PanMacmillan, 1982)

Tuchman, Barbara W.: The March of Folly.: From Troy to Vietnam (New York, 1990 edn.)

War Cabinet Minutes, September-November 1917, U.K. National Archives, CAB 23, 24

Weizmann, Chaim: The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann, Series A – Letters vol. VIII, November 1917- October 1918 (Jerusalem, 1977)

Woodruff, William: Impact of Western Man. A Study of Britain`s Role in the World Economy 1750-1960 (London etc, 1966)