By Ian Portman

Abstract

Faced with increasing antisemitism in Europe towards the end of the 19th century, many Jews chose to join the great waves of European emigration to the United States. Since the high middle ages, most of the world’s Jews had settled in eastern Europe, under welcoming Polish and later repressive Russian rule. During the social ferment around the turn of the 20th century in western Russia, a large and active social democratic movement developed that played a major role in the first (failed) and second (successful) Russian revolutions. The adherents of this movement – the BUND – aimed to build a nation among the nationalities of the Russian empire, speaking their own language, Yiddish and staying at home where they belonged.

Other movements, however, focussed on the ancient Jewish states of the Levant and developed the notion of a “return” of Jews to the land of Israel (said to have been given to the Jewish people by God) which ceased to exist some two thousand years ago. Prominent among such groups were Christian protestant evangelicals in Britain. These developed, from the 17th Century onward, a doctrine of conversion of Jews to Christianity, often linked with their return to Jerusalem. Only in this way, could the devoutly-desired second coming of the Messiah be secured. This belief became widespread in the middle of the 19th century in Britain where it influenced the highest levels of politics.

Towards the end of that century, a thoroughly-assimilated Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist, Theodor Herzl, reacting to antisemitism in Vienna and Paris, proposed the founding of a Jewish nation-state – der Judenstaat. This encountered vociferous opposition from almost all the Jews of Europe. But Herzl’s careful and incessant knocking on the doors of powerful men in the capitals of Europe was to bring success for his movement in the new century, as rivalries between the great powers spun out of control and crashed into the First World War.

Contents

- Refugees

- Loving the Jews: The Evangelical Origins of Zionism

- Another kind of antisemitism

- Where did the Jews of Eastern Europe come from?

- The beginnings of Jewish Nationalism

- Zionism finds its feet

- Footnotes

Refugees

Hundreds of thousands of refugees – the most of them poor and desperate – were pouring into western Europe in search of bread and a roof over their heads. Jews were on the run from racist terror in eastern Europe. The Russian authorities suspected many Jews of revolutionary ambitions and they were generally (but falsely) assumed to be behind the assassination of the liberalizing Tsar Alexander II. His successor’s administration, desperate to reassert imperial authority over the restive regions, turned against his Jewish subjects and passed harsh laws restricting their liberty. Pogroms in the Russian Pale of Settlement [1] grew in brutality and frequency. Some forty Jews were murdered in the Pale in the 1880s. Between 1903 and 1906, a more deadly series of pogroms rolled across western Russia, claiming some 3000 lives – some seventy in Kishinev (now capital of Moldova) and at least 400 hundred in Odessa alone. Many, but certainly not the majority of Russian Jews concluded it was time to leave.

The Russian empire was not known for treating its minorities with kid gloves. The Moscow Patriarchate presided over the state religion and other believers were generally disadvantaged, often persecuted or sometimes driven from Russian lands. The non-Orthodox were despised as unbelievers and thousands of Catholics were deported to Siberia in the mid 19th century. At the same time, around half a million Muslims were driven from the Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire, Iran or further afield. At the south-eastern border of the Pale of Settlement began the lands of the Circassians, a mostly Muslim group who had lived since the 14th century along the northern Black Sea coast from Sochi and eastwards into the Caucasus mountains. A long war of attrition ended in the genocide of 1865. According to official Russian statistics, the population was reduced by 97 per cent. At least 200,000, and possibly several hundred thousand people died through ethnic cleansing, hunger, epidemics and bitterly cold weather.

In a series of large-scale military operations that lasted from 1860 to 1864, the Northwest Caucasus and the Black Sea coast were virtually emptied of Muslim villagers. Columns of the displaced were marched either to the Kuban plains or toward the coast for transport to the Ottoman Empire. […] One after the other, entire Circassian tribes were dispersed, resettled or killed en masse [2].

This along with the massacres and mass deportations of the Crimean Muslim Tatars was where “the Russian Empire ended up inventing the strategy of modern ethnic cleansing and genocide with Crimean Tatars and Circassians as the first victims of massive territorial extermination in the 1860s [3].”

As Russia expanded southwards, it emulated the western powers by establishing colonies. It viewed its newly-acquired populations as wild and untameable: these were “races” which were unable to modernise and doomed to die out [4].

But the harsh Russian policy met with little resistance from other European powers. It was generally understood that Muslims had no place in Christian Europe. That the Tsar’s troops were getting their hands dirty on the south-eastern frontiers gave no cause for serious alarm in Paris and London.

In the Pale of Settlement, military repression of the population on this scale was unknown. But state action was not the only force driving Jews from the east: the Jewish population of the Russian empire had increased fivefold between 1800 and 1900. Following the liberation of the serfs in 1861, ever more day-labourers were available for work – but often found none. As capitalism began to work its magic in Russia, and mechanisation spread in agriculture, labourers who did find work had to put up with starvation wages. Jewish residents were at an additional disadvantage and, at the turn of the twentieth century, many decided to travel west. Between 1880 and the First World War over two million Jews from the Pale of Settlement emigrated to the United States of America.

Although Jewish people had long been part of the scene in central European capitals, a sudden upsurge in migration around the turn of the twentieth century rang alarm bells throughout the capitals of north-western and central Europe. Berlin and Vienna witnessed a very obvious increase in Jewish refugees, especially into those cities where, since the 1870s, nationalist, antisemitic propaganda had become part of the daily political discourse. The newcomers dressed strangely and spoke and prayed in a way that many found disturbing. The health authorities warned against the spread of disease. In short a full blown refugee crisis.

Jews had long been accustomed in western Europe to mistreatment and occasionally fell victim to economically- or religiously-inspired deadly riots but the situation in many places had improved during the Enlightenment and further during the nineteenth century. Freedom of movement and citizenship, established in territories conquered by Napoleon offered many the chance to take part in the mainstream of European life. The contemporary Haskaleh or Jewish Enlightenment encouraged Jews to move out of the ghetto, physically and mentally. In greater Prussia and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Jewish minority was gradually emancipated and became widely accepted by metropolitan citizens. Nevertheless, towards the end of the century, dissatisfaction with the slow pace of reform and the promise of a better life in the New World led hundreds of thousands of German-speaking Jews to emigrate. They joined some 2.25 million non Jewish Germans fleeing poverty, lack of opportunity and political persecution. In Vienna, Jews, many long-established, had come to play a leading role among the business and cultural elites. Immigration of Jews had been largely tolerated and those who came were often single men – many of them with professional qualifications. They integrated with relative ease. But a good number of the new wave of refugees who came around the turn of the century were different. They were not merely indigent, but usually brought the whole family with them. Many spoke no German and seemed foreign. They wore the black clothing of orthodoxy. Established Jewish residents saw them as a threat.

In turn-of-the-century Britain – especially in the east of London, where most Jewish immigrants gravitated – the government could not fail to notice an increasingly hysterical tone in the nationalist press. The much vaunted “alien menace” was code for the Jewish menace. Public meetings of the British Brothers’ League – a quasi militia – stoked the fires of resentment at these impoverished people who undercut the wages of native Englishmen. In 1905 the Conservative government of the then Prime Minister Arthur Balfour passed the Aliens Act – the first peacetime law to restrict immigration in modern Britain – a law which in reality targeted Jews.

Loving the Jews: The Evangelical Origins of Zionism

At the same time, Balfour demonstrated a markedly philosemitic bent. He had been raised as a Protestant by his mother in a strict evangelical tradition. Lady Blanche Gascoyne-Cecil had inculcated in her son through intensive daily study of the Bible, a literal, evangelical interpretation of the holy book in which both the old and the new testaments were considered of equal importance.

Like Balfour, Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had also been raised in an evangelical tradition, in his case in non-conformist Wales. He once remarked: “I was brought up in a school where I was taught far more history of the Jews than about my own land. I could tell you all the kings of Israel. But I doubt if I could have named half a dozen of the Kings of England. […] We were thoroughly imbued with the history of [the Jewish] race in the days of its greatest glory.”

The evangelical movement comprised a number of long-established non-conformist sects with a Calvinist proclivity but by the mid 19th century much of its doctrine had become widespread among the clergy of the Anglican church.

First promulgated in the 16th century in Geneva, John Calvin’s reformist doctrine spread rapidly from Geneva throughout Europe, especially in Strasbourg and then to Germany. It soon sprang over the channel to Scotland and England. The first mass-produced, bible printed in England was the Geneva Bible; it was widely read and discussed. At the start of the 17th century, a form of Calvinism caught on among the Puritans who, together with those opposed to the royal prerogative and distrusting the rise of Roman Catholic influence at court, demanded change. This came when parliament deposed and hacked off the head of King Charles I.

The printing of the Bible (previously available only in Latin and Greek) in various modern languages, led to a new evaluation of the importance of the Old Testament. Many children, born in the 17th and 18th centuries were given the names of Old Testament prophets.

In the Catholic church the new Testament was always given pride of place. But with the rise of Protestantism, the prophecies and claims of the Old Testament became widely available and contributed to a rise in prophetic speculation particularly regarding the status of the Jews. It became clear to many Protestant bible-commentators that the Jews were undoubtedly the chosen people of God and therefore deserved the interest and respect of Christians. This had the side effect that this new doctrine clearly distinguished Protestantism from Catholicism. Love and concern for the Jews became a badge of honour for reformed Protestants. In this way, the reformed Christians distanced themselves from the outrageous treatment of Jews by Catholics.

By this time, many evangelicals were ashamed of the attitude of the established churches towards the Jews. Gradually a doctrine developed among neo-Calvinists in Germany and Britain that Christians should honour Jews while at the same time being duty bound to convert them to (Protestant) Christianity. In the late 18th century, leading British churchmen developed this concept further, discovering in St. Paul’s letter to the Romans a God-ordained duty to assist modern Jews to “return” to Palestine .

Great Britain: chosen by God to return the Jews

It is important to note that, long before the notion of a “return” to Palestine had been seriously considered by mainstream Jewry, it had become a well-established theme among many Protestants.

Britain – thought to be the physical counterpart of the “New Jerusalem” – had been chosen by God to undertake this task . This was not entirely without an element of self interest since scripture implied (in this contested reading) that the gathering in of the Jews in Palestine would be a precondition for Christ to return at the end of time. This was an outcome devoutly to be desired. The Jews, according to evangelical belief, would then be given a last opportunity to convert by the returned Messiah before the final judgment. The fate of those who might refuse to convert was seldom mentioned. Naturally, leading Jewish thinkers found these ideas absurd – even insulting. A handful of (mostly German) Jews, did, however, convert, and contributed greatly to an industrious, wide-reaching, although ultimately not very successful missionary effort among their former co-religionists .

Following the French Revolution in 1789 which was seen as foreboding the collapse of the old order throughout Europe, the idea rapidly gained ground that the end of the world was indeed nigh: the conversion and “restoration” of the Jews became all the more urgent. The tireless engagement of the much-admired social reformer, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury advanced the evangelical agenda among leading politicians with many of whom he was closely related. He was for many years actively involved in the London Society for Promoting of Christianity among the Jews, a well-funded attempt to convert Jews as part of preparations for their return to Palestine .

Although Shaftesbury was a well-connected politician with international reach, and aware of developments in the Ottoman Empire, he had a certain blind spot. In his 1854 diary, an entry dated 17. May reveals:

All the East is stirred; the Turkish empire is in rapid decay; every nation is restless; all hearts expect some great thing. . . . Syria “is wasted without an inhabitant”; these vast and fertile regions will soon be without a ruler without a known and acknowledged power to claim domination. There is a country without a nation; and God now, in His wisdom and mercy, directs us to a nation without a country. His own once loved, nay, still loved people, the sons of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob.

His efforts led to the opening of an Anglican church in Jerusalem and the appointment of a British consul which soon led to rival powers doing the same. Shaftesbury thought strategically and used his political connections to great effect.

The race to establish a presence in “the Holy Land” was on. In later years, responding to anti-Jewish riots in the Russian “Pale of Settlement”, Lord Shaftesbury sent Revd. William Hechler on a mission to investigate the conditions of the Jews in Russia which marked the first contact between the well-established Christian Zionists and the nascent Jewish nationalist movement in eastern Europe.

In Britain, by the mid-to late 19th century, the hope for the restoration of the Jews had become mainstream with concrete political consequences. It formed part of the belief-system transmitted to Arthur Balfour by his mother and the re-conquest of Jerusalem for the Christian world became a goal for the prime minister during the First World War.

Following the British conquest of Jerusalem in 1917, David Lloyd-George noted with approval: “the capture by British troops of the most famous city in the world which had for centuries baffled the efforts of Christendom to regain possession of its sacred shrines.[5]”

The strength of both the prime minister and the foreign secretary’s belief in God and bible prophecy contributed indisputably to their espousal of the cause of Zionism. [6]

Another kind of antisemitism

Following the introduction of the Code de Napoléon – a legal codification of the rights and responsibilities of free citizens – in territories conquered and in many cases delineated by the Grande Armée, the idea of a state based on laws and reason marked a major milestone on the march to modernity. Napoleon’s emancipation of Jews in territories under his control seemed to herald a new era for European Jewry [7]. German states were among the first to legislate equality for citizens of the Jewish faith. The Grand Duchy of Hesse granted them equal rights in 1808, the Kingdom of Westphalia in 1811, the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt and Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1812, the Kingdoms of Prussia and Württemberg in 1828 and 1830 respectively.

But as the young states struggled to define themselves, other notions came to the fore. The new nationalisms drew more on romanticised concepts of shared religion, tradition, language and, increasingly, racial identity. Many German delegates to the 1815 Congress of Vienna resisted demands for Jewish emancipation and far-reaching reforms in many German territories took decades to arrive.

Although the widespread, religiously-motivated slaughter of Jews in western Europe of the Middle Ages was a thing of the past, resentment of Jewish people as an economic threat raised its ugly head occasionally. What changed in the 19th century was rapid and disruptive technological development and new forms of finance and global capitalism.

The currency reforms in Austro-Hungary (1811-16) and Prussia (1821), designed to unify and regulate the means of exchange led to a massive devaluation which practically destroyed the savings of those who had managed to set something aside.

As a result of the so-called freeing of the peasants and the gradual end of feudalism – which came late to many German speaking areas – traditional ties between landowners and farmers broke down. Landowners were now free to buy and sell their properties, which many did. Peasants in Prussian-controlled territory were required to purchase their liberty which often resulted in their continuing to work as before but under the additional burden of paying their landlords in installments for their freedom. The gradual introduction of new crops, farming methods and machinery led in practice to many landowners throwing peasants off the land, employing them only seasonally or as bonded labourers in inefficient cottage industries at low wages. This led to the “pauperisation” of great swathes of the population.

The resulting mass movement of people into urban areas disrupted traditional patterns of employment there and created a high degree of insecurity among workers and owners of small businesses. In many cities, in the mid 19th. century, some 70 to as much as 90 per cent of people were plunged into poverty. In Germany, a fast-growing heavy industry took advantage of the desperate condition of the poor and employed workers at hunger-wages. Those who could not find work sank further into misery. Marx saw in this process the transformation of feudal into capitalist exploitation: “The expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil is the basis of the whole process.[8]” As the century wore on, unrest began to threaten the social dispensation. In 1848 widespread demonstrations broke out in the Rhineland, in Berlin and in other large cities and in short order, two revolutions were brutally suppressed. This led to a massive rise in emigration to the United States.

It can be argued that the resulting cheapness of labour in the 19th. century was the main motor of the rapid concentration of capital and the rise of German manufacturing power which, by the end of the century had become the mightiest in continental Europe.

To deflect blame for the misery of the working poor and the social catastrophe, a scapegoat was needed – and found: the Jews. Often adaptable and industrious, some Jewish citizens were doing well. Many were increasingly integrating into mainstream society and becoming more secular.

Their new, improved status was, however, resented by those who were losing out to the dramatic economic shifts underway.[9] Jews who had lived in Europe for hundreds of years were seen as foreign to mainstream society. This scapegoating was mainly tolerated – and sometimes promoted– by nationalistic and right-wing parties.

Late nineteenth century Europe was awash with myths about race and breeding. The pseudo-scientific racial theories of Comte Arthur de Gobineau, (Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, 1855) considered northern European “Aryan” human stock to be superior to the lazy and feckless Celts and Latins. The British anthropologist, Francis Galton established the theory of eugenics in his work Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development in 1883. The doctrine of Racial hygiene (which provided the theoretical basis for the Nazis’ mass murder of disabled people) became fashionable. The German Darwinist and eugenicist Alfred Plötz (Grundlinien einer Rassenhygiene, 1895) focussed on “the degeneration of the Nordic race” (Entnordung). These themes were taken up and amplified by the mainstream press.

In this toxic atmosphere, the position of European Jewry became increasingly difficult. If nations were to be determined by race and religion, where did that leave them?

Meanwhile, the political and military establishments of major European countries, increasingly engaged in colonial projects in Europe, Africa and Asia, believed themselves to be racially superior to the people they oppressed. National honour and destiny became their watchwords. The British, French, Germans and Belgians preached of their civilizing role in Africa, while exploiting the cheap resources and indentured labourers of “the dark continent” on a massive scale.

While western European states were occupying ever more land in Africa, the Russian empire was consolidating its grip on lands acquired by conquest and diplomacy between 1791 and 1835. Having grabbed much of Poland and all of what is now Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus, the Tsarist state treated the non-orthodox inhabitants – mainly Catholics and Jews– harshly. Most of the Ashkenazi Jewish population were confined to the “Pale of Settlement” – where the great majority already lived – and they were subjected to increasing repressions. The Pale comprised some 20 per cent of Russian territory and at its greatest extent was larger than modern France, Germany and Italy combined. Towards the end of the 19th century, despite emigration, the Jewish population had reached nearly five million – the largest population of Jews on the planet. Most chose not to emigrate [10].

Where did the Jews of Eastern Europe come from?

The origins of the Ashkenazi [11] Jewish people of eastern Europe is the cause of much historical debate. Some Israeli scholars believe that they had arrived there indirectly from Palestine, from where, according to semi-official biblical narrative [12], they had been expelled by the Romans in 70 -71 AD, and again in 132 AD. How many Jews were expelled is, however, impossible to determine. In fact, the writer acknowledged as the greatest 20th century historian of Jewish history, Prof. Salo Wittmayer Baron, found no evidence to suggest that any expulsion took place but saw a long process of migration to more developed areas of the Roman empire [13].

At the beginning of the first millennium, Judaism welcomed and gained many new adherents around the Mediterranean sea [14]. Most of these converts were North African, Greek or European converts who had no family connection with the Levant. In first century Rome, conversions to Judaism from the officially-sanctioned Roman state religion were becoming so common that members of the Jewish religion were expelled outside the city walls several times for aggressive missionary activities.

Historians such as Shlomo Sand [15] argue that troublesome elites and religious leaders were banned by the Romans, but most of the Jewish population of Roman Syria Palaestina remained where they were, working the land. Following the Muslim invasion of the Levant in 635-40 AD it is likely that, in time, they converted to Islam, just as most Egyptian Christians (Copts) did after the conquest of Egypt.

Sand also espouses the Khazaria theory of the origins of Eastern European Jews. The Khazar Khaganate existed between the mid 7th and late 10th centuries C.E. and stretched from western Ukraine to Crimea and east to the Caspian sea. Not caring to choose between Christianity, as practised in the Byzantine Empire to the south west and Islam, the religion of the Abbasid empire to the south east, the Khan and his court opted for Judaism as their state religion. Numerous Jewish scholars travelled there to instruct these important converts. The extent to which the people converted is, however, unknown. Many writers – ranging from the French scholar of Christianity and Semitic civilizations, Ernest Renan to the popular British-Hungarian novelist and intellectual, Arthur Koestler have suggested that Ashkenazi Jews are descended from the Kahzars. This view is also held by most Karaite Jews. Many geneticists, however, find no connection between modern Ashkenazi Jews and the Khazars of 1500 years ago, although others dispute this fiercely.

But it is not disputed that Jewish merchants travelled with the Roman army during its expansion into northern Europe, especially under Julius Caesar and Augustus. By the early middle ages, significant communities had developed along the river Rhine – in Cologne, Mainz, Speyer and elsewhere.

Al-Andalus

In the 7th century, north African Jews, joined the Muslim armies that swept through the area in 690 AD, and went on to assist in the conquest of Visigoth Spain where they played an active role in the cultural and economic life of Andalusia for several hundred years. Al-Andalus (known in Hebrew as Sefarad ) became the most important religious and cultural centre of Judaism. The great Sephardi philosopher, Maimonides, the most influential scholar of the Torah in the middle ages, taught and wrote in a Muslim society in Europe. But in the 8th century, Christian armies commenced a 750 year long campaign to drive Muslims out of the Iberian peninsula. The Holy See adopted a policy of re-establishing Christianity by the sword. In newly Christianised statelets, Jews were seen as collaborators with the alien Muslims: a potential fifth column. Gradually, over hundreds of years, some Jews converted to Christianity while more and more Jews began to seek a home elsewhere: in the Maghreb, Egypt, the Byzantine Empire – and later in the Ottoman Empire where they were welcomed.

A northern European haven for Jews

In March of the year 1000, the Roman Pope Otto III travelled to pay his respects at the tomb of St. Adalbert in Gniezno, today in central Poland. There he was received with great ceremony by the Catholic duke Bolesław the Brave. During this event, the Pope is said to have recognized Poland as a nation state. Twenty-five years later, Bolesław I was crowned king of Poland, a state which was distinguished by long periods of open governance, tolerance and respect for the rule of law.

Jews were already present here in the 10th century, some migrated from Andalusia as the Christian Reconquista got under way and a hundred years later thousands more came, fleeing excesses against the Jewish populations in the Rhineland and elsewhere in the Holy Roman Empire during the first Crusade.

By the high Middle Ages, Poland had grown to be one of the largest states in Europe. In 1264, a General Charter of Jewish liberties mandated unprecedented rights and privileges to Jewish citizens. Karaite Jews from the Crimea (who believed they were descendants of Khazaris) were invited by Prince Vytautas the Great of Lithuania at the turn of the 14th Century and were granted land and special privileges.

In the 16th century Polish territory expanded with the establishment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under a common monarch.

By the mid 1600s, some three-quarters of all the world’s Jews lived on Polish territory, their forebears having enjoyed 700 years of relative peace and security in the heart of Catholic Europe.

While the imperial expansion of Poland brought opportunities, it also brought dangers for the Jews many of whom moved eastwards too. Polish nobles, took over large tracts of land in the east known as the “wild fields” (now modern central and southern Ukraine along the river Dniepe.)

This take-over was, of course, resented by the native population. Many were Cossacks – a warlike people of diverse origin who were often runaway serfs. They were fiercely Orthodox and their distaste for Catholic oppression was augmented by widespread resentment of the Polish nobles’ estate managers and rent collectors who were often Jews. Commonwealth Jews also secured a virtual monopoly on the sale of alcohol [16], which further stoked popular animosity. It did not bode well for the future that many of the conquered peoples of the East believed Jews to be agents of the occupying power.

The Deluge

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, gradually weakened by internal conflicts, was shocked to be attacked by Cossacks in 1648: a skirmish which developed into a war which ended with the establishment of an independent Cossack state. But this was just the beginning of a catastrophic decline known as “the Deluge.” In the second half of the century, Poland was invaded repeatedly by various Swedish armies, which looted its treasure and killed tens of thousands of civilians. Swedish forces occupied most of western Poland, destroying nearly 200 towns and cities. In 1654, Russian forces invaded and captured the eastern provinces. With great difficulty, in time, the Polish crown reasserted it control over much of its territory, but it was now in a an extremely weakened condition.

In the 18th century, as a result of another series of wars and treaties, the country was dismembered by Prussia, Austro-Hungary and Russia as each grabbed treasure and territory until nothing was left of Poland. During this period, many thousands of Catholics and Jews fell victim to the greed and religious intolerance of the invaders.

The beginnings of Jewish Nationalism

Jewish Russians: absorbed by conquest but not welcome

By 1796, most Polish Jews were living under the rule of the Russian Tsar, Pavel I, who also took the title of King of Poland. They now found themselves subjected to restrictions such as being required to live in specific areas, forbidden to work the land and, in most cases, being denied access to higher education. Pavel’s successor, Nicholas I, a conservative and repressive Tsar, tightened the screws by requiring Jewish youths to attend boarding schools away from their families and to serve from the ages of 18 for 25 years in the Russian armed forces. These measures were conceived as a means of integrating the Jewish population. The few Jews who converted to Russian Orthodoxy were accepted as full citizens.

Tsar Alexander II came to power in 1855. He was somewhat progressive and recognised the need to modernise his vast empire. He set about this by emancipating bonded labourers and allowing more freedom of movement to national minorities. He also mitigated anti-Jewish edicts in the Russian Empire, rescinding forced conscription and allowing Jewish students into universities. He authorised Jewish emigration out of the Pale.

But the Russian people as a whole wanted more freedom and a better life. Revolutionary groups of all shades were not content with half measures. Members of the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) revolutionary party made several attempts on the Tsar’s life, the last of which succeeded in March, 1881.

His son and successor, Alexander III presided over a nationalist, right-wing administration with vengeful characteristics. The interior minister accused Jews of being behind the murder [17] and took the opportunity to implement repressive edicts − the May Laws− withdrawing many of the measures of his father and again limiting the freedom of Jews to travel or engage in agriculture, commerce and industry. They were required to move into certain towns and cities of the Pale.

The official promotion of antisemitic propaganda and the tightening restrictions on Jewish citizens were an effort to deflect popular anger from the government and focus it on the alleged “enemy within”. But a widespread radicalisation of Russian intellectuals was now well underway and they were mobilising against the Russian authorities.

Revolutionaries!

Jewish Russians played a leading role in the struggle for socialism in the Empire. Increasingly active as workers in cities, many joined the proletarian struggle for a just society. They were especially active in this respect in Belorussia and Lithuania. In the 1890s it was common for Jewish workers and intellectuals to organise study groups for the advancement of socialist ideas. The majority were held in Russian and promoted revolutionary solidarity instead of minority national identity.

Foremost among many revolutionary groups, however, was the Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter Bund in Litah, Poyln un Rusland, known in the West as the Bund. Founded in Vilnius in 1897 by delegates representing some 3,500 members, the Bund played a central role in creating the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), with three of the nine delegates at the founding session. Their practical engagement for and wide support among working people contrasted starkly with the well-heeled elite who gathered around Theodor Herzl in Vienna whose Zionist movement was launched in the same year. But the Bund insisted on Jewish nationality in a socialist system within a Russian federation of nationalities.

Vladimir Menem, a leading Bundist put his theory of nationalities like this:

Let us consider the case of a country composed of several national groups, e.g. Poles, Lithuanians and Jews. Each national group would create a separate movement. All citizens belonging to a given national group would join a special organisation that would hold cultural assemblies in each region and a general cultural assembly for the whole country. The assemblies would be given financial powers of their own […] Every citizen of the state would belong to one of the national groups, but the question of which national movement to join would be a matter of personal choice and no authority would have any control over his decision. The national movements would be subject to the general legislation of the state, but in their own areas of responsibility they would be autonomous and none of them would have the right to interfere in the affairs of the others.[18]

The Bundists promoted the widely-spoken Yiddish as their future national language.

Unwaveringly secularist in its beliefs, the Bund also relinquished the idea of the Holy Land and the sacred tongue. Its language was Yiddish, spoken by millions of Jews throughout the Pale. This was also the source of the organization’s four principles: socialism, secularism, Yiddish and doyikayt or localness. The latter concept was encapsulated in the Bund slogan: “There, where we live, that is our country [19].”

The Bund disapproved greatly of Zionism and considered the idea of emigrating to Palestine to be political escapism.

In 1905, following the Battleship Potemkin incident [20] towards the end of the disastrous Russo-Japanese war, uprisings to protest the condition of sailors proliferated and took on a revolutionary character. The Bund was especially active in organizing and in street fighting. Its popularity grew enormously − membership rose to almost 40,000. But following the defeat of the uprising, its influence diminished. The Bund focussed now on activism among the work force and on developing Yiddish cultural groups. In 1906 it evolved into a social democratic movement and allied itself with the Menschvik tendency of the RSDLP.

The revolutionary ferment of the period, the increase in numbers of Jewish workers, their growing proletarization and the development of Jewish national sentiments – both cultural and political –set the stage for their participation in the Revolution of 1917 and the struggle for national rights within that context.

In fact, for Jewish Russians, most of whom remained on Russian territory, the Communist Revolution of 1917 was to bring the formal emancipation and citizenship of which they had long dreamed. Following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, legal discrimination of all kinds against Jews was cancelled. The Petrograd Soviet marked this with a special session in March, 1917. A Jewish delegate compared the new found freedom with the delivery of the Jews from Egypt…

This is not to deny that antisemitic sentiment was present among the masses whose favour the Bolsheviks courted. At the first Congress of the Soviets in July, 1917 a resolution was passed, that condemned antisemitism as a form of counterrevolution. In July, 1918, a front page headline in Pravda read: “To be against the Jews is to be for the Tsar!”

Anti-Jewish violence continued to mark the revolutionary period, however, despite significant efforts by the soviets to contain it. Some pro-Bolshevik mobs took part in anti-Jewish riots, but the majority of pogroms were the result of anti-revolutionary agitation. The White Army, led by former officers of the Russian imperial army orchestrated campaigns of anti-Jewish violence, resulting in the deaths of thousands of Jews in pogroms, especially in the Ukraine. During the revolutionary period, several million Russians died as a result of the civil war, on the battlefield, in massacres, through disease and starvation, among them a large but unknown number of Jews.

In the fevered atmosphere from the 1890s until the First World War, many Jews, both revolutionary and of the liberal secular mainstream, rebelled against the stifling, tradition-bound life of traditional, orthodox Judaism. They wanted to assimilate into Russian society, just as their western cousins were doing in their countries. But a small minority, mostly of a religious persuasion, joined groups proposing agricultural settlements in Palestine or in central Asia.

Green shoots of Zionism fail to make the desert bloom

Hovevei Zion (aka Hibbat Zion) was one such: a loose movement of local organizations throughout the Pale but centred in Odessa, promoting agricultural settlements in Ottoman Palestine and offering perspectives for those oppressed by political and economic exclusion. As we have seen, in the wake of the May Laws, Jewish agricultural workers could find no employment so some saw resettlement as a way out of their difficulty. Suspicious of any Jewish political activity, but won over by the idea of Jews moving elsewhere, the Russian authorities eventually approved the establishment of the Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz Israel in 1890. Hovevei Zion’s membership grew to around 8,000 by the end of the century. Hovevei Zion groups formed a kind of proto-Zionist movement, but without a unified or clearly-defined political programme. This was about to change.

Dr. Yehuda Leo Pinsker, of Odessa was of secular persuasion. Originally an assimilationist and a Russian patriot, he became convinced that a new, global approach to the Jewish Question (as it was known) was needed. He crystallized his thinking in a ground-breaking pamphlet Autoemancipation [21], 1882.

We understand ourselves not only as Jews; we feel ourselves as men. As men, we too wish to live and be a nation just as the others.

The ghostlike apparition of a wandering corpse, of a people without unity or organization, without land or other bonds, no longer alive, and yet walking among the living − this outlandish form without precedence in history, … lacking a model or a likeness could not fail to leave a strange, outlandish impression on the imagination of the nations. And if the fear of ghosts is something inborn, and achieves a certain justification in the psychic life of mankind, why be surprised at the widely-accepted impression produced by this dead but still living nation?

To the modern reader, the frank and often racist tone of Zionist discourse comes as something of a shock. It must be borne in mind, that nationalism and racism coloured much European political writing at that time: Leon Pinsker was reflecting a widely accepted view of race and nationality.

For Pinsker:

The goal of our present endeavours must be not the “Holy Land,” but a land of our own. […] We need nothing but a large tract of land … sufficient for the settlement, in the course of time, of several million Jews. This tract might form a small territory in North America, or a sovereign Pashalik (province) in Asiatic Turkey…

Intervention from an unexpected quarter

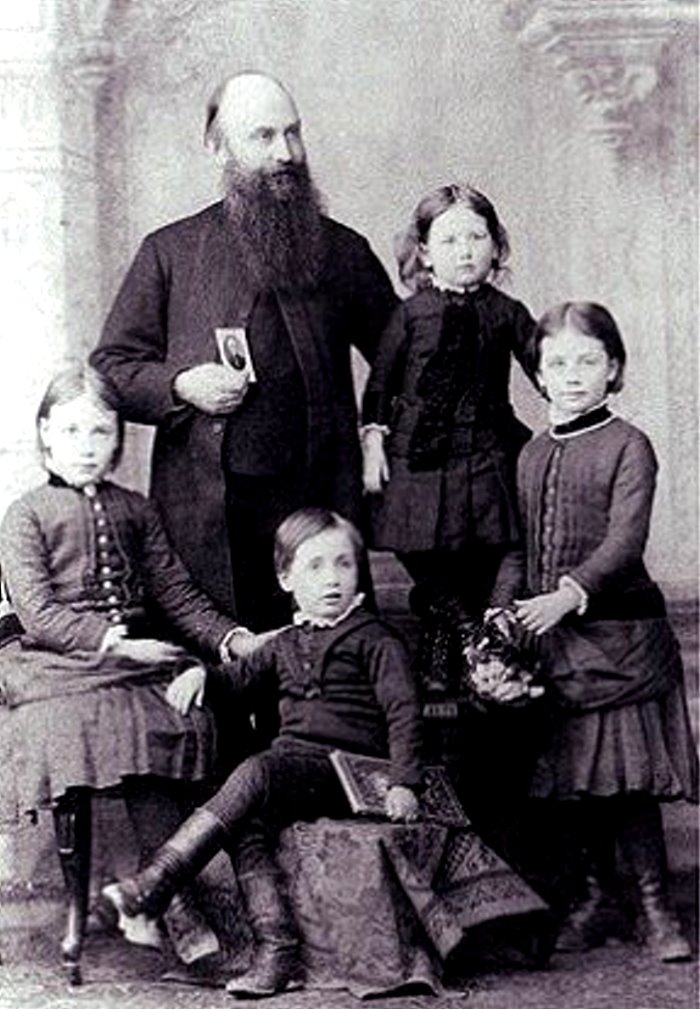

Just after he had published Autoemancipation, in January 1882, Pinsker was surprised when a somewhat eccentric, bearded man with piercing blue eyes paid him a visit in Odessa. This was the English evangelical preacher, Dr William Hechler (see Loving the Jews). He was there ostensibly to enquire about the condition of the Jews in Russia and was mightily pleased to learn of the stirrings of Jewish nationalism but horrified that Pinsker had no preference as to where the Jewish nation should be founded.

his children

Hechler introduced him to the pietistic interpretation of prophesy. He showed him verses from the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Amos from which, Hechler concluded, the gathering in of the Jews in Palestine (the term most used by Christian and Jewish settlers) was a necessary condition for the second coming of the messiah. God was about to bring the Jewish exile to an end [22].

Now Pinsker felt the religious Jews who longed for Jerusalem were on a hiding to nowhere. The appearance of a visionary Christian on a mission who told him he had foreseen that the return to Zion would begin in 1897 must have struck him as bizarre. Nevertheless, the reverend returned to England and reported to his sponsor, Lord Shaftesbury — the elderly yet still active and influential Christian Zionist politician, that he had persuaded Pinsker that Palestine should be his only goal.[23] Whatever the truth of Hechler’s claim, within two years the non-religious Dr Pinsker had become chairman of Hovevei Zion.

Naturally, as revolution or emigration were being hotly discussed, there were also periods of tranquillity and places untouched by the uproar. David Ben-Gurion – who was later to become Prime Minister of Israel – grew up in eastern Poland with parents who were leading members of Hovevei Zion. He remembered:

For many of us, anti-Semitic feeling had little to do with our dedication [to Zionism]. I personally never suffered anti-Semitic persecution. Płońsk was remarkably free of it … Nevertheless, and I think this very significant, it was Płońsk that sent the highest proportion of Jews to Eretz Israel from any town in Poland of comparable size. We emigrated not for negative reasons of escape but for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland [24].

Palestine: a land without people?

Not all members of Hovevei Zion had a Jewish state in mind – some were deeply religious and considered the building of a new temple in Jerusalem would be blasphemous unless directed by a specific sign from God. Then there was the question of the people who already lived in that part of the Ottoman Empire. Although many Zionists subsequently perpetuated the myth that the land was practically empty, some, who were in contact with the settlements in Palestine, were compelled to face reality. By 1870, the area later officially recognised as Palestine had a population of approximately 380,000 people: 300,000 — 88 per cent — were Muslims or Druze, eight per cent Christian, and four per cent were Jews [25]. In 1914-15, according to official Ottoman Census statistics, there were 722,143 people in Palestine, of whom 602,377 were Muslims, 81,012 Christians and 38,754 Jews (of whom 12,332 were Ottoman citizens and the rest immigrants. [26]

A group of activists known as “cultural Zionists,” did worry about Palestine’s majority Arab population. Preeminent among these was the Russian writer Asher Ginsberg, who took the pen name Ahad Ha’am (Hebrew for “one of the people”) by which he is best known. He had joined Hovevei Zion but sought a revival of Jewish culture centred on a limited, symbolic presence in that land with so much resonance for the Jewish faith. Ginsberg’s take on Zionism later attracted a number of leading intellectuals such as Martin Buber, Albert Einstein, Harry Sacher and Hannah Arendt. For Ginsberg, the goal of Zionism should be to revive Judaism not to rescue Jews. The Jewish “homeland” he interpreted as a spiritual renewal. Mass migration to Palestine was impractical and unacceptable. Settlers would be obliged to assist the Arab population to develop the country and should treat them with respect. Although Ginsberg was a friend of Pinsker’s, he deeply opposed colonizing a land inhabited by people of a different culture and religion.

In 1891, Hovevei Zion asked him to visit Palestine to report on conditions there. This fact-finding tour opened Ginsberg’s eyes; in The Truth from the Land of Israel, he wrote:

From abroad, we are accustomed to believe that Eretz Israel is presently almost totally desolate, an uncultivated desert, and that anyone wishing to buy land there can come and buy all he wants. But in truth, it is not so. In the entire land, it is hard to find tillable land that is not already tilled … If the time comes when the life of our people in Eretz Israel develops to the point of encroaching upon the native population, they will not easily yield their place [27].

Hovevei Zion’s agricultural colonies, financed by Baron Edmond de Rothschild and run by his agents, were for the most part economically unviable and their monoculture system hopeless. They were barely eking out a living, and making do with philanthropy and by exploiting cheap Arab labour. Jewish purchases had led to land speculation, resented by the indigenous population. Under these circumstances, significant expansion of the Yishuv (the Zionist project in Palestine) was neither possible nor desirable. In any event, of the approximately two and a half million Jews who left Russian controlled territory between 1800 and 1913, just over 3 per cent chose to move to Palestine. Hovevei Zion had clearly failed to mobilize eastern European Jewry

Zionism finds its feet

The Dreyfus Affair

In France, during the so-called Belle Époque the standard of living among the upper middle classes rose dramatically while many workers and unemployed people slipped further into poverty, breeding the resentment documented in Emil Zola’s novels. The country was plagued by right-wing Catholicism and jingoistic nationalism. A corrupt and racist military elite brought matters to a head in 1894 by accusing Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a proudly patriotic Jewish artillery officer from Alsace, of offering military secrets to Germany. The charges were patently false and the only evidence was that of an amateur graphologist who imagined it was Dreyfus’ handwriting on an incriminating note taken by a French housekeeper at the German embassy in Paris. The trial took place largely in secret and was influenced by other forged documents insinuating that Dreyfus was a homosexual. He was convicted in short order and sentenced to be deported to Devil’s Island off French Guiana. A huge outcry developed. The novelist Emil Zola penned the celebrated appeal J’accuse! (for which he himself was imprisoned) and under popular pressure, a second trial took place. Again Dreyfus was found guilty and his sentence extended. He was, however, then pardoned by President Emile Loubet. But it was not until 1906 that his name was finally cleared. During the whole affair, a rabid antisemitism shook the Third Republic. The outcome led to a profound reordering of French political life. The subsequent liberal victory played an important role in pushing the far right to the fringes of French politics.

Despite his humiliation, Dreyfus remained a French patriot to the end of his life, and held Zionism to be merely a dream. Reporting on the events was the young Austro-Hungarian writer Theodor Herzl, correspondent for the Viennese Neue Freie Presse. He later wrote that the affair had convinced him on the need to establish a Jewish homeland (although some scholars have cast doubt on this, noting that Zionism among Jews was a well-established topic in the 1880s and that Herzl had himself experienced antisemitic taunts as a student.) In any case, the widespread distaste at the events in France laid the groundwork for a frank, public discussion of the future of European Jewry.

Paul Johnson writes in his book History of the Jews [28]:

The left won an overwhelming electoral success in 1906. Dreyfus was rehabilitated and made a general. … In 1895, Herzl was not to foresee the victory of the Dreyfusards … [whose] outright victory in France…reaffirmed the view that there at least the Jews could find not only security but opportunity and a growing measure of political and cultural power.

Herzl seizes the moment

Theodor Herzl was born to a wealthy businessman, Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl and his wife, Jeannette in Budapest, Hungary. The family moved to Vienna in 1878 where Theodor studied law at the University of Vienna. His desire to be an engineer came to nothing, but he dabbled in playwriting and journalism, with which he had some limited success. Like many of his class and education, Herzl admired German culture and took the need to integrate into the national mainstream for granted [29].

His attachment to Judaism was practically non-existent, his knowledge of things Jewish rather vague, consisting principally of memories of occasional visits to a Budapest synagogue from his childhood. But by the end of the century, in the light of increasing attacks on Jews in eastern Europe and under the influence of Russian Jewish thinking, he, too, came to believe that something had to be done about “the Jewish question.” He toyed at one point with the idea of a mass conversion to Christianity [30]. In time. however, he came to the conclusion that Jews should leave Europe and establish their own homeland. Argentina came to mind but also Palestine. In Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), published in February 1896, he argued that Jews had been and would continue to be persecuted wherever they settled, even in civilized nations. He concluded: “The Jews who wish for a State will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes.”

Herzl was not the first European Jew to consider the idea of migration to Palestine. The Perushim − orthodox Jews who came to believe in the imminent appearance of the Messiah – emigrated to Jerusalem in the second half of the 19th century and Pinsker’s Hovevei Zion movement encouraged small-scale agricultural settlement in Palestine. These efforts, however, met with limited success: most Jews in Palestine lived in abysmal poverty, and many wanted to get back home to Europe as soon as they could.

Forgotten in the shadows of Herzl’s renommée are others — proto-Zionists — notably Moses Hess, a friend of Karl Marx, who converted Engels to Marxism. But Hess was attacked by Marx and Engels in their Communist Manifesto of 1848 and accused of not being a true revolutionary. In the 1850s, Hess abandoned the central Marxist concept of class struggle, and moved towards a theory of racial competition. He also re-evaluated his Jewish roots, changing his name to Moses/Moise (from Moritz) as a protest against the growing integration of Jewish Germans into the secular mainstream. He became, in short, a proponent of Jewish religious nationalism. In 1861 Hess wrote Rome and Jerusalem: The Last National Question [31], an appeal for the emigration of the “Jewish race” to Palestine. It received little attention at the time and was soon forgotten.

Sixty years later, however, the thoroughly bourgeois Theodor Herzl praised the almost forgotten Hess. Herzl opined that he would not have written Der Judenstaat had he read Rome and Jerusalem. The compliment does not, however hide the fact that the two men’s concepts of Zionism were quite different.

As we have seen, Herzl was not a religious man but like many European decision-makers of the time, he saw nations and peoples in racist terms. He came to believe that antisemitism was built into the character of non Jews – a racist belief propagated by many Zionists to this day. According to this doctrine, those who belonged to a nationality with a homeland would always reject the outsider and antisemitism would exist so long as the Jews had no nation of their own. In his introduction to Der Judenstaat, we read:

I think the Jewish question is no more a social than a religious one, notwithstanding that it sometimes takes these and other forms. It is a national question. The unfortunate Jews are now carrying the seeds of Anti-Semitism into England; they have already introduced it into America.

As a general principle, his idea has been proved wrong. He could not, of course know, that antisemistism would prove a short-lived problem in Britain and the United States where a large majority of people continue to view their Jewish citizens in a positive light. In the United States, residual antisemitic sentiment has continuously decreased in the last twenty years [32].

Israeli Historian Benny Morris considered that Herzl foresaw that antisemitism might be harnessed for the realization of Zionism:

Herzl regarded Zionism’s triumph as inevitable […]. The European political establishment would eventually be persuaded to promote Zionism. Herzl recognized that anti-Semitism would be harnessed to his own Zionist-purposes [33].

In his diaries, as Herzl discusses how Jews will emigrate from Europe, we read: “The anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.[34]”

Hillel Hakin points out in the Jewish literary magazine Mosaic [35] that Herzl was more or less unknown in the wider Jewish world:

It was Herzl’s good luck, it might have seemed at the time, that The Jewish State went largely unnoticed when published. This was so not only in Germany and Austria, where the very idea of Zionism was a curiosity, but in Jewish Eastern Europe as well… Although it has been said that Herzl appeared in the skies of East European Jewry with a sudden, comet-like brilliance, that was hardly the case. A cursory review of the Hebrew press suggests that there was almost no interest in him until the weeks preceding the [first] Zionist congress … . Even when his existence was acknowledged, as when an article of his … appeared in the Warsaw Hebrew daily Hatsefirah, it was with no sense of the role he was about to play. Introducing the article, Hatsefirah’s editor Naḥum Sokolov described Herzl, for the benefit of readers who had never heard of him, as an author, “well-known in the literary world of Vienna,” whose ideas, though “their practicality can be challenged,” deserved a hearing.

[Herzl] demonstrated the difference between the Yiddish-speaking and Hebrew-reading Jews of Europe’s East, with their inborn rootedness in their people’s traditions and culture, and the deracinated Jews of the West, who needed anti-Semitism to remind them of who they were.

But Theodor Herzl, although an unknown quantity among European Jews, was an extremely active and dedicated organiser. A keen networker and enthusiastic diarist and correspondent, Herzl’s papers reveal a man who strove to make an impression on the movers and shakers of the imperial order. He had little time for religion nor for politics of the left or of the right: he was a one topic lobbyist and a top-down leader. He would talk with whoever he could – as long as that man might advance the Zionist case.

He used his contacts with the press and his connections with Jewish organisations in England, France and Germany as well as in the east of Europe to drum up support for an international Zionist conference. Initially he wanted to hold this in Munich, but there he met with such fierce opposition from the conservative and well-integrated Jewish community that he decided to hold the first Zionist Congress in Basel from 29th to 31st August, 1897.

Herzl’s experience in the theatre had taught him the necessity of making an impression, so despite inner misgivings whether the event would stir any interest, he worked tirelessly to make his congress a success. It was a formal affair: men were required to appear in full morning dress. The proceedings were designed to make important people sit up and take note.

An atmosphere of optimism pervaded the proceedings, and there was enthusiastic reaction in much of the world ‘s press [36]. But the Zionist ideal was generally rejected by the overwhelming majority of Jews in Europe and in America [37].

Many, now well-established and increasingly secular citizens with a Jewish background found the idea of a nation state for Jews threatened their position in their respective homelands. Religious Jews pointed to widely-known sacred texts that condemned the gathering of Jews into Palestine without God’s explicit call as blasphemy. The Chief British Rabbi Dr. Hermann Adler, in an interview in the London Daily Mail in 1897 [38], said:

While I yield to no one in being an ardent lover of Zion […] I believe that Dr. Herzl’s idea of establishing a Jewish State there is absolutely mischievous. It is contrary to Jewish principles, the teaching of the prophets and the traditions of Judaism. It is a movement … which can be entirely perverted and may lead people to think that we Jews are not fired with ardent loyalty for the country in which it is our lot to be placed. And in saying this I believe, I am expressing the opinion of, with a few exceptions, the entire Anglo-Jewish community.

But Herzl had gathered around him a small group of believers who dedicated themselves to the promotion of “the new Jew”. Among them was Max Nordau, a widely-published intellectual, who married a Danish Christian and was exclusively secular in outlook. Nordau’s most widely-read work was Degeneration in which he attacked the fin die siècle cultural and physical decline of western society. Nordau was convinced that especially the “Jewish race” had degenerated and urgently needed regeneration through his program of physical and mental exercises to create the new Muskeljude. He blamed assimilation for the state of European Jewry, which he likened to those Spanish Marranos who converted to Christianity to preserve their social position.

I think with horror of the future development of this race of new Marranos, who are normally sustained by no tradition and whose soul is poisoned by hostility toward their own and strange blood, and whose self-respect is destroyed through the ever present consciousness of a fundamental lie [39].

In his introduction to Der Judenstaat [40], Herzl makes it clear, however, that assimilated Jewish citizens would also benefit from the new state:

The “assimilated” would profit even more than Christian citizens by the departure of faithful Jews; for they would be rid of the disquieting, incalculable, and unavoidable rivalry of a Jewish proletariat, driven by poverty and political pressure from place to place, from land to land. This floating proletariat would become stationary. Many Christian citizens – whom we call Anti-Semites – can now offer determined resistance to the immigration of foreign Jews. Jewish citizens cannot do this, although it affects them far more directly; […] they feel first of all the keen competition of individuals carrying on similar branches of industry, who, in addition, either introduce Anti-Semitism where it does not exist, or intensify it where it does.

The “assimilated” give expression to this secret grievance in “philanthropic” undertakings. They organize emigration societies for wandering Jews. There is a reverse to the picture which would be comic, if it did not deal with human beings. For some of these charitable institutions are created not for, but against, persecuted Jews; they are created to dispatch these poor creatures just as fast and far as possible. And thus, many an apparent friend of the Jews turns out, on careful inspection, to be nothing more than an Anti-Semite of Jewish origin, disguised as a philanthropist.

It did not occur to Herzl, that his own efforts to dispatch the “wandering Jews” to another continent might also be considered racist.

This notion that Jews comprised a race shattered centuries of mainstream Jewish belief that they were brothers and sisters in religion. The return to Jerusalem, prayed for each year at the end of the Seder (passover) feast, by Jews all over the world, was not meant literally: it was a spiritual Jerusalem, much as Bob Marley, quoting Psalm 137, later sang of the return to Ethiopia “By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion.” For most Jews at the turn of the 20th century, only the imminent return of the Messiah would bring about a return to Zion.

Dr. Yaad Biran of Haifa University points out:

Zionism, like other national-liberation movements, preferred a romanticized conception of the past, according to which it would create a new common denominator for the Jews. In order to negate the present, Zionism had to internalize anti-Semitic stereotypes: to criticize the deteriorating life of Eastern European Jews and offer this Diaspora-style redemption. The danger was that romanticized nationalism was liable to deteriorate into fascism – because, if we are good and special, we have the right to take action in defense of our wonderful identity [41].

This “romanticised nationalism”, this idea that Jews constituted a race, differed from the national struggles of the early nineteenth century which drew their ideas from Voltaire and Rousseau and were catapulted into reality by Napoleon. Towards the turn of the 20th century, however, as imperialism and nationalist racism reached a new high point, it seemed to Herzl clear that “the Jewish race” needed a Jewish state. It was a colonialist ideology [42].

Herzl’s concept began to spark interest among non-Jews, especially those who feared an influx of refugees from eastern Europe and the undesirable political consequences. And, as we have seen, an influential group of evangelical Christians had been actively promoting the Restoration of the Jews to Palestine for some considerable time.

When browsing in a Vienna bookshop in the spring of 1896, the chaplain of the British embassy in Vienna, came across Der Judenstaat − and was electrified. He arranged an introduction through an acquaintance, and thus began a long and for Herzl very helpful relationship. The clergyman was none other than the active Anglo-German Restorationist, Revd. Dr. William Hechler who had pointed Leon Pinsker towards Palestine 14 years earlier in 1882.

Hechler was by now established in Vienna and made assiduous use of contacts through the embassy. He remained, however, eccentric in his appearance and his beliefs about the Jews and Jerusalem, centering around his abstruse recalculations of biblical prophetic verses was not at all to Herzl’s taste. As he had with Pinsker, Hechler assured Herzl that he was the agent of the Almighty and was fulfilling prophesy.

Initially distrustful of the man, Herzl nevertheless came to value Hechler’s contacts with German royalty in his quest to get in touch with influential people.

Hechler’s former employee and friend, the Grand Duke of Baden, became a keen Zionist. He put Herzl in contact with Kaiser Wilhelm II whose support Herzl hoped for in the matter of establishing a Jewish entity in Palestine.

In the summer of 1896, Herzl made contact with the Ottoman government, meeting the Grand Vizier in Istanbul. Herzl’s idea was to offer the Ottoman state great deal of money (which he hoped to rise from Jewish-owned banks) to help alleviate Turkey’s debts in exchange for being granted a Jewish state in Palestine. But the offer was rejected. Despite many later approaches, the Sultan or his Vizier had always brushed Herzl off, perhaps recognising that to grant Islam’s third holiest site to Zionist immigrants would cause uproar throughout the empire.

In 1898, Wilhelm II proposed a trip to Istanbul and the Levant. He invited Herzl to meet him near Jerusalem. Naturally, Herzl hoped the Kaiser could persuade the sultan to play along. But the meeting in the Kaiser’s encampment near Mikveh Israel was a disappointment. The German Foreign Minister von Buelow, mindful of the opposition of Jewish German bankers and of the Jewish press to a move which could call their loyalty into question, persuaded Wilhelm not to promote the scheme.

Despite this setback, Herzl recognized Hechler’s deep commitment to the Zionist cause and became a lifelong friend. Hechler was present at the first World Zionist Congress and, became “not only the first, but the most constant and the most indefatigable of Herzl’s followers.[43]”

So the determined and long-established efforts of Christian Zionism and the still uncertain proposals of a thoroughly-assimilated Jewish journalist came together against vociferous opposition from almost all the Jews of Europe. Herzl’s careful and incessant knocking on doors in St. Petersburg, Vienna and London was to bring success for his movement in the new century, as rivalries between the great powers spun out of control and crashed into the First World War.

© Ian Portman, Stuttgart, Germany. Email: info@balfour.de

Footnotes

[1] The Pale of Settlement, to which most Jews were restricted covered some 20 per cent of Russian territory It comprised land now mostly belonging to what are now Ukraine, eastern Poland, Lithuania, Moldova and Belarus. Russia’s policies of containment of its nationalities continues to this day, with restrictions on movement of Caucasians and Turkic minorities and discrimination against them.

[2] Charles King, The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus, p 95. Oxford University Press; November, 2009

[3] Arno Tanner, The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe – The History and Today of Selected Ethnic Groups in Five Countries. p 19. East-West Books. 2004.

[4] Irma Kreiten (Southampton University), The Russian final subjugation of Northwestern Caucasus: Colonial Atrocities and European Responsibilities, October 2008. Available online at: http://www.circassianworld.com/pdf/Colonial_atrocities.pdf

[5] Marx, Kapital 1: 669. Also: Marx, Grundrisse, 471-514.

[6] It would be naive, however to imagine that politically adept, experienced statesmen would be blind to the more pressing matter of war goals. The cabinet was determined to protect the Suez Canal and to control the expected riches of the Persian Gulf. The land route to India – a vital source of raw materials and a major trading partner – was also an important consideration. So the British looked favourably on the establishment in Palestine of a friendly state that would owe a debt to Great Britain.

[7] Napoleon was simply implementing the original principles of the French revolution. He also thought European Jews might be of assistance to him in maintaining his European empire. After he invaded Palestine in 1799, his progress slowed at Acre. The French revolutionary newspaper Le Moniteur Universelle, proclaimed on 22nd May: “Bonaparte has published a proclamation in which he invites all the Jews of Asia and Africa to gather under his flag in order to re-establish the ancient Jerusalem. He has already given arms to a great number, and their battalions threaten Aleppo.” The status of this proclamation is questionable: no original has been found. In any case, the British chased Napoleon out of Palestine. In 1806, the Emperor invited Jewish communities to send delegates to the Grand Sanhedrin (named after a traditional ancient Hebrew general assembly) which met in 1807. The assembled Jews were grateful for Napoleon’s granting them their natural rights and accepted, at the Emperor’s urging, that “Paris is our Jerusalem.” See also Ben Weider (1997). Napoléon et les Juifs (in French) (PDF); http://www.napoleonicsociety.com/french/pdf/NapoleonJuifs.pdf

[8] Marx, Kapital 1: 669. Auch: Marx, Grundrisse, 471-514.

[9] An early example of this type of antisemitism can be seen in the Hep-Hep riots in Germany of 1819. Following disastrous harvests which led to widespread hunger, the riots began in Würzburg and spread across Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden, then north, continuing sporadically for two months. Several Jewish citizens were murdered, many beaten, and thousands driven out of their communities. The failed harvests in many parts of Europe were caused by the explosion, in 1815, of the Indonesian volcano, Tambora – the greatest observed eruption of all time. Ash from the event brought about disastrous harvests in northern Europe for several years and led to mass migration from Europe to America – including more than half of the population of Ireland. It should be noted that a number of people including several prominent figures offered shelter to affected Jewish citizens.

[10] Despite further appalling massacres by White Russian forces during the civil war, Jews’ position improved somewhat in the immediate aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution: many of the revolutionaries were themselves Jews and Lenin condemned antisemitism several times. By the 1930s, Jews formed 1.8 percent of the Soviet population but between 12 and 15 percent of university students. See Arad, Yitzhak (2010). In the Shadow of the Red Banner: Soviet Jews in the War Against Nazi Germany. Gefen Publishing House, Ltd. p. 133.

[11] Most were Ashkenazi, however there were smaller communities of Sephardi, Caucasian and Bukhari Jews.

[12] The first book of Maccabees which deals with these events has no official status in Judaism or in the protestant churches. It does, however, appear in Catholic and Orthodox bibles. Scholars differ widely on the reliability of the narrative.

[13] Salo Wittmayer Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews (New York/Philadelphia, 1952), vol. 2, pp. 122-; .Columbia University Press, 1937.

Also see Israel J. Yuval (Professor of Jewish History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) The Myth of the Jewish Exile from the Land of Israel, Duke University Press, 2004 (article). In A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People pp. 102-3, Section: The Jewish Settlement after 140 CE we read:

“Although Jews were still forbidden to reside in Jerusalem, the authorities tended to ‘turn a blind eye’ when they arrived in the city of pilgrimages, provided they stayed only a short time. The settlements in the south — in the Shepehlah and the Jordan valley — continued to exist and the percentage of the urban population in these places increased. The Galilee remained almost entirely Jewish…Economically, the lot of the Jewish population improved in the generation following the religious persecution by Hadrian….some Jews who had left the country returned, a few prisoners-of-war managed to return to their settlements, and those already settled never thought of leaving the Holy Land…..”

[14] See Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People, Verso Books, 2009.

[15] Dr Shlomo Sand, Professor of History, Tel-Aviv University.

[16] See http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/165467/jews-and-booze

[17] In fact only one Jewish female student was found to belong to the group Narodnaya Volya ( = ‘People’s Will’) that carried out the assassination.

[18] Medem, V. 1943. Di sotsial-demokratie un di natsionale frage (1904) pp. 173-219. See also http://homepage.univie.ac.at/herbert.preiss/files/Plasseraud_How_To_Solve_Cultural_Identity_Problems.pdf

[19] 60th Anniversary of the Israeli Bund The last word, in Yiddish, auth: ‘bennym’ Haaretz, 19 July, 2011, [Hebrew] cited and translated by Tony Greenstein at https://azvsas.blogspot.de/search?q=bund (retrieved November 15th 2017), Available here: https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.1181006

[20] Neal Bascomb, Red Mutiny: Eleven Fateful Days on the Battleship Potemkin, Houghton-Miflin, New York, 2007

[21] German original text: https://archive.org/details/LeoPinskerAutoemanzipation

[22] Victoria Clark, Allies for Armageddon: The Rise of Christian Zionism, Yale University Press, 2007, p. 9. See also The Road to Balfour: The History of Christian Zionism by Stephen Sizer

[23] Paul C. Merkley, The Politics of Christian Zionism 1891-1948; Routledge, 2012; p 16

[24] David Ben Gurion, Memoirs, World Publishing Company, 1970 p. 36

[25] Alexander Schölch, Palestine in transformation, 1856-1882, 1993. S 26. Die Statistik basiert sich auf osmansichen Zensusdaten.

[26] Salman H. Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917 -66, Palestine Land Society, London 2010 p 21;

[27] Alan Dowty, Ahad Ha’am’s “Truth from Eretz Yisrael”, Zionism, and the Arabs, Israel Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2000) 154–181.

[28] Paul Johnson History of the Jews, St. Martin’s Press, 1988. Quoted in the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs,

Also: Allan C. Brownfeld in Herzl Misread the Meaning of the Dreyfus Affair, 14 September, 2009. https://www.wrmea.org/2006-september-october/a-century-ago-zionism-founder-herzl-misread-the-meaning-of-the-dreyfus-affair.html

[29] Elon, Amos, 1975. Herzl, p. 23, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[30] The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl. Vol. 1, ed. Raphael Patai, translated by Harry Zohn, p. 7. Available online at: https://archive.org/stream/TheCompleteDiariesOfTheodorHerzl_201606/TheCompleteDiariesOfTheodorHerzlEngVolume1_OCR_djvu.txt

[31] Moses Hess, Rom und Jerusalem, online at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Rome_and_Jerusalem

[32] See FBI statistical tables here: https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/. In summary: 1996: 1,182 incidents, 2006: 967 incidents, 2016: 684 incidents. Latest available statistics (2014) for total number of arrests for all categories of crimes were 11,205,800. Anti-Jewish hate crimes account for about 0.006 per cent of incidents in the U.S.A. This level is still unacceptable, but it remains very small.

[33] Benny Morris, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-200, p. 21; Vintage Books, New York

[34] The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl. p. 84.

[35] https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/2016/10/what-ahad-haam-saw-and-herzl-missed-and-vice-versa/

[36] z.B, in the Times of London, 4. Sept, 1986: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/56/Zionist_Congress%2C_The_Times%2C_Saturday%2C_Sep_04%2C_1897.png

[37] Fromkin, David (1990). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. Avon Books.

[38] July 30, 1897, cited here: http://www.jewishmag.com/145mag/herzl_hechler/herzl_hechler.htm

[39] Address by Max Nordau at the First Zionist Congress (August 29, 1897) http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/address-by-max-nordau-at-the-first-zionist-congress

[40] Herzl, Der Judenstaat. In English available here: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/quot-the-jewish-state-quot-theodor-herzl. The German original is here: https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Der_Judenstaat

[41] Yaad Biran, 60th Anniversary of the Israeli Bund The last word, in Yiddish, Haaretz, 19 July, 2011, [Hebrew]

[42] see Gilbert Achcar, The Zionist Project’s Duality: Escaping Racist Oppression and Reproducing It in Colonial Context. Achcar is Professor of Development Studies and International Relations at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Article also available here: http://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/34667/The-Zionist-Project%E2%80%99s-Duality-Escaping-Racist-Oppression-and-Reproducing-It-in-Colonial-Context

[43] Paul Merkley, The Politics of Christian Zionism 1891-1948, 1998,Frank Cass & Co, London also Jerry Klinger, http://www.jewishmag.com/145mag/herzl_hechler/herzl_hechler.htm