Stephen Sizer

The Promised Land – From the Nile to the Euphrates?

I will establish my covenant as an everlasting covenant between me and you and your descendants after you for the generations to come, to be your God and the God of your descendants after you. The whole land of Canaan, where you are now an alien, I will give as an everlasting possession to you and your descendants after you; and I will be their God. (Genesis 17:7-8)

Those who insist that the Jewish people are God’s ‘chosen people’, also insist that the promises made to Abraham and the Patriarchs, concerning the land bequeathed to them, are promises that apply to his physical descendants today. So the contemporary State of Israel is seen as evidence of God’s continuing protection and favour toward the Jewish people. David Brickner sees the occupation of Palestine in 1948 and Jerusalem in 1967 as the fulfilment of the promises made to Abraham and the Patriarchs:

I believe the modern day state of Israel is a miracle of God and a fulfilment of Bible prophecy. Jesus clearly said that “Jerusalem would be trodden down of the Gentiles until the time of the nations is fulfilled” (Luke 21:24). It has been 50 years since the founding of that state, but only 30 years since Jerusalem came under the control of Jews for the first time since Jesus made that prediction. Could it be that “this generation shall not pass until all these things are fulfilled?”[1]

So, the Third International Christian Zionist Congress held in Jerusalem in 1996, expressed the belief of many in affirming:

According to God’s distribution of nations, the Land of Israel has been given to the Jewish People by God as an everlasting possession by an eternal covenant. The Jewish People have the absolute right to possess and dwell in the Land, including Judea, Samaria, Gaza and the Golan.[2]

In this chapter we will consider what the Bible has to say about the significance and purposes of the Promised Land as well its geographical extent. Then we will look at whether the land was intended as an ‘everlasting possession’ of the Jewish people or whether they were only temporary residents. Then we will examine the terms under which they were allowed to return after the exile, and whether the kingdom was nationalistic or universal. Finally we must consider what Jesus and the apostles have to say about all this.

The Significance and Purposes of the Promised Land

In God’s redemptive plan, he chose Abram, from what is today, Iraq, and called him to leave his home in Ur by the Euphrates and go to the land of Canaan. These were the promises God made:

The LORD had said to Abram, “Leave your country, your people and your father’s household and go to the land I will show you. “I will make you into a great nation and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” So Abram left, as the LORD had told him.” (Genesis 12:1-4)

After Ishmael was born to Abram and Hagar, God ratified the covenant once more (Genesis 17:1-8).

The covenant promises made to Abraham were repeated once more after Isaac was born (Genesis 22:16-18). It was subsequently made to Isaac ‘because Abraham obeyed me’ (Genesis 26:2-4) and then finally to his grandson Jacob (Genesis 28:13-15). There is no doubt that the vision of a ‘Promised Land’ was central to the hopes and aspirations of God’s people as they languished in slavery in Egypt as well as during their long wanderings through the wilderness of Sinai (Exodus 23:27-33). The promise of land with specific boundaries demonstrated the trustworthiness of God and his faithfulness in caring for those who called upon his name (See Genesis 26:3-5; Exodus 6:1-8; Joshua 24:11-27). God’s faithfulness in the land promises was celebrated throughout the history of Israel, notably in Psalm 105.

O descendants of Abraham his servant, O sons of Jacob, his chosen ones. He is the LORD our God; his judgments are in all the earth. He remembers his covenant forever, the word he commanded, for a thousand generations, the covenant he made with Abraham, the oath he swore to Isaac. He confirmed it to Jacob as a decree, to Israel as an everlasting covenant: “To you I will give the land of Canaan as the portion you will inherit.” (Psalm 105:6-11. See also 37-45)

Clearly, the covenants were intended to instill trust in God and faithful obedience from his people. Yet, the present ambiguous borders of Israel are only a fraction of those God apparently intended for the Jewish people.

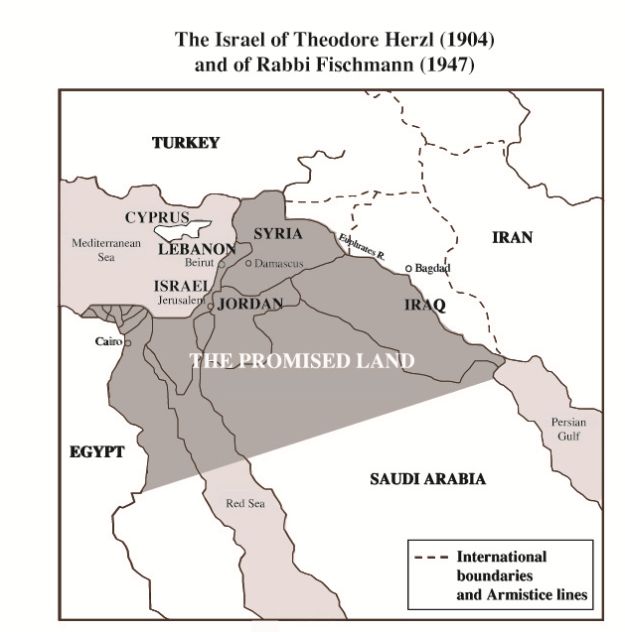

The Geographical Boundaries of Israel: From Egypt to Iraq?

The boundaries of the land God promised to Abraham and his descendents are demarcated in Genesis 15. “On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram and said, ‘To your descendants I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the Euphrates.’” (Genesis 15:18). The ‘river of Egypt’ most likely refers to one of the tributaries of the Nile. The word in Hebrew ‘nahar’ denotes a large river and this is how early Aramaic translations along with Jewish commentaries identify the location (See 1 Chronicles 13:5). The Euphrates begins in Turkey and flows through Syria and Iraq before entering the Persian Gulf.

If these boundaries were applied today, and depending on the route of the southern border from Eilat to the Euphrates, parts of Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, and even Kuwait and parts of Saudi Arabia would be incorporated. Some Zionist groups lay claim to all this territory using the term ‘Eretz Israel HaShlema’ to denote the whole or complete land of Israel. While most secular Israeli’s today would not identify with these ‘biblical’ borders, the founders of Zionism, including Theodore Herzl, Vladimir Jabotinsky and David Ben-Gurion, certainly did. They saw the creation of the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan, in 1922, as a betrayal of the British Mandate because it denied Zionists the right to settle there.

Nevertheless, it is significant that after nearly 60 years since the foundation of the State of Israel, successive governments have failed to declare what they regard as their territorial boundaries. Israel must be the only country in the world that has not yet recognised its own borders.

Cyrus Scofield, in a footnote to Deuteronomy 30:5 in his Reference Bible claims, ‘It is important to see that the nation has never as yet taken the land under the unconditional Abrahamic covenant nor has it ever possessed the whole land’.[3] Arnold Fruchtenbaum elaborates further on why this claim to much of the Middle East is nonnegotiable.

So, then, according to the Scriptures, three promises are made with regard to the land: first, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were all promised the possession of the land; second, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were promised the possession of the land; and third, the boundaries of the promised land extended from the Euphrates River in the north to the River of Egypt in the south… At no point in Jewish history have the Jews ever possessed all of the land from the Euphrates in the north to the River of Egypt in the south. Since God cannot lie, these things must yet come to pass. Somehow or other, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob must possess all the land, and second, the descendants of Abraham must settle in all of the Promised Land.[4]

The problem with this kind of literalism is that it goes too far, setting Scripture against Scripture. Advocates have to ignore the way the Bible itself interprets the promises made to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The books of Joshua, 1 Kings and Nehemiah all indicate that the promises were fulfilled. Having entered Canaan, the Bible tells us, ‘So Joshua took the entire land, just as the Lord had directed Moses.’ (Joshua 11:23). At the end of the book of Joshua, the same assessment is repeated but rather more emphatically (Joshua 21:43-45).

However, in chapter 23, in Joshua’s farewell address before he dies, he says:

Remember how I have allotted as an inheritance for your tribes all the land of the nations that remain—the nations I conquered—between the Jordan and the Great Sea in the west. The LORD your God himself will drive them out of your way. He will push them out before you, and you will take possession of their land, as the LORD your God promised you. (Joshua 23:4-5)

Clearly Joshua and the Israelites did not conquer all the territory and yet he believed ‘Not one of all the Lord’s good promises to the house of Israel failed; every one was fulfilled’ (Joshua 21:45). So either the writer of Joshua was not a ‘literalist’ in the modern sense of the word or perhaps he had the wrong maps.

In 2 Samuel, the writer describes how King David ‘went to restore his control along the Euphrates River’ (2 Samuel 8:3-4) suggesting that, even if only briefly, the kingdom had by then extended this far north. Then under King Solomon, the boundaries of Israel were consolidated, extending from Egypt to the Euphrates. The writer of 1 Kings uses the metaphor of sand on the seashore from Genesis 22:17 to show that he understood the boundaries of Solomon’s kingdom to be a fulfilment of the promises made to Abraham (1 Kings 4:20-21, 24).

Tiphsah, mentioned in this passage, was a city on the west bank of the Euphrates. By around 440 BC Nehemiah could look back and give thanks to God for the fulfilment of his promises, again using the language of Genesis (Nehemiah 9:7-9, 25).

It is hard to see how these clear statements, which demonstrate the faithfulness of God, can be ignored or reconciled with the ultra-literalist claims of those who insist the promises have yet to be fulfilled.

Everlasting Possession or Conditional Residence?

The land of Canaan was given to the Israelites as a sign of God’s grace and mercy, not because of their size or significance (Deuteronomy 7:7). Nor was the land a reward for their righteousness or integrity. In fact, God describes them in rather less than complimentary terms as a ‘stiff-necked people’ (Deuteronomy 9:5-6). Moses and the Hebrew Prophets repeatedly state that the land belongs to God and residence there is always conditional. For example,

‘The land must not be sold permanently, because the land is mine and you are but aliens and my tenants’ (Leviticus 25:23).

In Jeremiah 2, God says, ‘I brought you into a fertile land to eat its fruit and rich produce. But you came and defiled my land and made my inheritance detestable.’ (Jeremiah 2:7 emphasis added). It is God’s land not theirs (see also Jeremiah 16:18). Because the Land belongs to God, it cannot be permanently bought or sold. The Land is never at the disposal of Israel for its purposes. Instead it is Israel who is at God’s disposal. The Jews remain aliens and tenants in God’s Land. Perhaps this is why it is only referred to as the ‘land of Israel’ six times in the whole of the Bible. The reason is clear. It is God’s land, as is the rest of the earth (Psalm 24:1).

Zionists, however, like to emphasize that God promised the land from Egypt to Iraq as an ‘everlasting possession.’ (Genesis 17:8). So the International Christian Embassy says:

We simply believe the Bible. And that Bible, which we understand has not been revoked, makes it quite clear that God has given this land as an eternal inheritance to the Jewish people… According to God’s distribution of nations, the Land of Israel has been given to the Jewish People by God as an everlasting possession by an eternal covenant. The Jewish People have the absolute right to possess and dwell in the Land, including Judea, Samaria, Gaza and the Golan.[5]

They therefore invariably oppose the dismantling of Jewish settlements in Gaza and the Occupied Territories, justify the Separation Barrier, assist Jewish people from around the world to move to Israel and support the colonisation of Palestine. Exobus is just one of many organisations funding the transportation of Jews to Israel[6], while Christian Friends of Israeli Communities actively encourage churches to adopt and fund illegal Jews-only Settlements in the Occupied Territories.[7]

Genesis 17:8 does indeed describe the land as an ‘everlasting possession.’ However, a text without a context is a pretext and Genesis 17:8 is a good example. The very next verse provides the context in the form of a conditional clause.

Then God said to Abraham, ‘As for you, you must keep my covenant, you and your descendants after you for the generations to come’… Any uncircumcised male, who has not been circumcised in the flesh, will be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant (Genesis 17:9, 14).

Residence in the land was therefore always conditional. In Deuteronomy, residence in the land is explicitly made conditional on adherence to the Law. Notice the “if” and “because”:

” If the LORD your God enlarges your territory, as he promised on oath to your ancestors, and gives you the whole land he promised them, because you carefully follow all these laws I command you today—to love the LORD your God and to walk always in obedience to him…” (Deut. 19:8-9)

At the end of Deuteronomy, God promises his people blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience.

|

Blessings for Obedience |

Curses for Disobedience |

| If you fully obey the LORD your God and carefully follow all his commands I give you today, the LORD your God will set you high above all the nations on earth. All these blessings will come upon you and accompany you if you obey the LORD your God…The LORD will grant that the enemies who rise up against you will be defeated before you. They will come at you from one direction but flee from you in seven… Then all the peoples on earth will see that you are called by the name of the LORD, and they will fear you. (Deuteronomy 28:1-3, 7, 10) | However, if you do not obey the LORD your God and do not carefully follow all his commands and decrees I am giving you today, all these curses will come upon you and overtake you: You will be cursed in the city and cursed in the country… |

The LORD will cause you to be defeated before your enemies. You will come at them from one direction but flee from them in seven… You will be uprooted from the land you are entering to possess. Then the Lord will scatter you among all nations, from one end of the earth to the other. (Deuteronomy 28:15-16, 25, 63-64)

In Leviticus, the language is even more explicit, leaving no room for doubt. Even while the Israelites were still wandering in the desert, the Lord uses some of the most graphic language in the Bible to spell out the basis for their future residency in the Promised Land (Leviticus 18:24-28).

The opening chapter of Joshua provides a good example of the promises and conditions given to the Israelites as they are about to enter Canaan.

|

Unconditional Promise |

Conditional Clause |

| get ready to cross the Jordan River into the land I am about to give to them—to the Israelites. I will give you every place where you set your foot, as I promised Moses. Your territory will extend from the desert to Lebanon, and from the great river, the Euphrates—all the Hittite country—to the Great Sea on the west. No one will be able to stand up against you. (Joshua 1:2-5) | Be careful to obey all the law my servant Moses gave you; do not turn from it to the right or to the left, that you may be successful wherever you go. Do not let this Book of the Law depart from your mouth; meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do everything written in it. Then you will be prosperous and successful. (Joshua 1:7-8) |

As the conquest begins we find by Joshua 7, the Israelites are threatened not just with exile but with destruction.

Israel has sinned; they have violated my covenant, which I commanded them to keep. They have taken some of the devoted things; they have stolen, they have lied, they have put them with their own possessions. That is why the Israelites cannot stand against their enemies; they turn their backs and run because they have been made liable to destruction. I will not be with you anymore unless you destroy whatever among you is devoted to destruction. (Joshua 7:11-12)

Notice the conditional clause, “I will not be with you… unless…” So, the unconditional promises concerning the land were always clarified or supplemented by conditional clauses. These made continued residence in the land dependent on adherence to the covenant terms. Near the end of Joshua’s final speech he repeats the warning:

If you violate the covenant of the LORD your God, which he commanded you, and go and serve other gods and bow down to them, the LORD’S anger will burn against you, and you will quickly perish from the good land he has given you. (Joshua 23:16)

The warning of the prophets, in explaining the reasons for their exile from the land, reinforce the promises and warnings of the Mosaic Law. Jeremiah 7 is just one example, “Through your own fault you will lose the inheritance I gave you. I will enslave you to your enemies in a land you do not know, for you have kindled my anger, and it will burn forever” (Jeremiah 7:4).

Thankfully God’s anger did not literally ‘burn forever’ against the Jewish people because he sent Jesus to take their punishment and ours upon himself (Isaiah 53:4-6). The pattern set in the Law and Prophets is nevertheless one which the existence of a largely secular State of Israel tests.

Repentance, Revival and Restoration: But in which Order?

From their beginnings in the early decades of the 19th Century, organisations such as the London Jews’ Society, promoted the belief that the Jewish people would come to recognise Jesus as their Messiah, be restored to the land once more and then Jesus would return. Scofield claimed that biblical prophecies foretold a third restoration to the land coinciding with the return of Jesus: ‘Israel is now in the third dispersion from which she will be restored at the return of the Lord as King under the Davidic Covenant’.[8] Until the beginning of the 20th Century, the consensus was that God would restore the Jewish people to Palestine as a Christian nation.

With the birth of the Zionist Movement, and growing numbers of secular Jews emigrating to Palestine, Christian writers began to seek an alternative prophetic interpretation. E. Schuyler English who supervised the revision of the Scofield Reference Bible in 1967, adds the following footnote to Deuteronomy 30:5 which is absent from Scofield’s original. ‘…when the nation walked in conformity with the will of God, it enjoyed the blessing and protection of God. In the twentieth century the exiled people began to be restored to their homeland.’[9] In the 1984 edition the wording was revised yet again to read ‘In the twentieth century the exiled people were restored to their homeland.’[10]

Conveniently, the vision of the ‘dry bones’ in Ezekiel 37 seemed to explain what was happening. Hal Lindsey offers this interpretation, adding capitals for emphasis, in case you miss the plot:

Ezekiel 37:7-8 … is phase one of the prophecy which predicts the PHYSICAL RESTORATION of the Nation without Spiritual life which began May 14, 1948 … Ezekiel 37:9-10 … is phase two of the prophecy which predicts the SPIRITUAL REBIRTH of the nation AFTER they are physically restored to the land as a nation … The Lord identifies the bones in the allegory as representing ‘the whole house of Israel.’ It is crystal clear that this is literally predicting the restoration and rebirth of the whole nation at the time of Messiah’s coming [Ezekiel 37:21-27].[11]

Charles Spurgeon called this kind of dodgy interpretation, ‘exegesis by current events’[12] for interpreting Scripture in the light of history rather than the other way round. Mocking the speculations of some of his contemporaries he wrote,

Your guess at the number of the beast, your Napoleonic speculations, your conjectures concerning a personal Antichrist—forgive me, I count them but mere bones for dogs; while men are dying, and hell is filling, it seems to me the veriest drivel to be muttering about an Armageddon at Sebastopol or Sadowa or Sedan, and peeping between the folded leaves of destiny to discover the fate of Germany.[13]

In this instance, Lindsey and others have reversed the clear and unambiguous process outlined in the promises and warnings of the Law and Prophets who teach that repentance leads to restoration, not the other way round. It is hard to see how this novel interpretation of Ezekiel can be reconciled with the warnings given just a few chapters earlier. In Ezekiel 33, it seems the Lord anticipated the reasoning of those who arrogantly claimed rights to the land because of the promise made originally to Abraham:

Son of man, the people living in those ruins in the land of Israel are saying, ‘Abraham was only one man, yet he possessed the land. But we are many; surely the land has been given to us as our possession.’ Therefore say to them, ‘This is what the Sovereign LORD says: Since you eat meat with the blood still in it and look to your idols and shed blood, should you then possess the land? You rely on your sword, you do detestable things, and each of you defiles his neighbor’s wife. Should you then possess the land?’ (Ezekiel 33:23-26).

The short answer is ‘no’. God warns that they will be exiled from the land because of their arrogance and disobedience.

It is also hard to believe that the Jewish exiles in Babylon would have found Ezekiel’s prophecy about the ‘dry bones’ much comfort had he told them it wasn’t actually for them but for their descendents living in the 20th Century. This kind of thinking that places our own generation at the centre of God’s purposes isn’t new. Intentionally or otherwise, this ‘chronological arrogance’ relegates previous generations to a kind of ‘warm up’ act or prelude to the main event which is now. In the following few verses Ezekiel leaves us in no doubt as to the consequences of disobedience:

I will make the land a desolate waste, and her proud strength will come to an end, and the mountains of Israel will become desolate so that no one will cross them. Then they will know that I am the LORD, when I have made the land a desolate waste because of all the detestable things they have done.’ (Ezekiel 33:25-29)

On the basis of such sober warnings it could be suggested that unless there is an imminent spiritual revival, Israel is more likely to experience another exile rather than a restoration. The Abrahamic and Mosaic promises were always conditional. ‘Obey and stay or rebel and be removed.’ The message of the Prophets was consistent with the warnings of the Torah. ‘Repent and then return’, never the other way round.

The Kingdom: Nationalistic or Universal?

While the boundaries of the land given to Abraham in Genesis 15 are clear. The question remains as to whom they were intended for. Even while the Israelites were wandering through the Sinai Desert, the Lord indicated through Moses that he had given a portion of the land to the children of Esau.

For a long time we made our way around the hill country of Seir. Then the LORD said to me, “You have made your way around this hill country long enough; now turn north. Give the people these orders: ‘You are about to pass through the territory of your brothers the descendants of Esau, who live in Seir. They will be afraid of you, but be very careful. Do not provoke them to war, for I will not give you any of their land, not even enough to put your foot on. I have given Esau the hill country of Seir as his own. (Deuteronomy 2:1-5)

The region of Seir, is between Mt Horeb and Kadesh Barnea in the Negev (Deuteronomy 1:1-2; 44-46). So the region south of Beersheva, although within the boundaries of the land given to Abraham, was now allocated to the Edomites. The Israelites were therefore prohibited from entering or settling in this area of the Negev. Those who insist on ‘biblical borders’ for Israel need reminding that the modern State of Israel is in possession of forbidden territory. Furthermore, the means by which they have colonized the Negev, through the forced expulsion of the indigenous Bedouin, is in clear breech of this passage. As the Israelites in their wanderings traveled north to the region of Moab, south east of the Dead Sea, God gave them further instructions:

Then the LORD said to me, “Do not harass the Moabites or provoke them to war, for I will not give you any part of their land. I have given Ar to the descendants of Lot as a possession… When you come to the Ammonites, do not harass them or provoke them to war, for I will not give you possession of any land belonging to the Ammonites. I have given it as a possession to the descendants of Lot. (Deuteronomy 2:9, 19)

This vast region was also ‘off limits’ to the Israelites because God had allocated it to the descendents of Lot, the Moabites and Ammonites. Today, Amman, the capital of Jordan, is named after their ancestors.

The kingdom of Israel reached its zenith in terms of extent, wealth, power and influence in the ancient world under King David and King Solomon (2 Samuel 8:1-14; 1 Kings 10:1-29). However, we learn that Solomon gave away cities in the Galilee to the Phoenicians. He traded the towns in the Acre Valley as far as Rosh Hanikra, just south of Tyre in Lebanon, in return for produce he needed for the construction of the Temple and his palaces in Jerusalem (1 Kings 9:11-13).

Ignoring the fact that Hiram wasn’t particularly impressed with them, it is significant that there were no prohibitions in the Mosaic Law on the giving away of territory to non-Jews. What appears to have mattered more were strategic and economic interests of the people rather than the land itself being somehow sacrosanct.

All was lost, however, when the kingdom was divided (1 Kings 11:31-39) and then first, in 722 BC, the northern tribes are taken captive to Assyria (2 Kings 17) and then beginning in 605 BC, the remnant of Judah are exiled to Babylon (2 Kings 25). During this time, God inspired Jeremiah to write a letter to the exiles in which he instructed them to settle down in Babylon and make it their home. Indeed, they are told to work and pray for Babylon’s peace and prosperity (Jeremiah 29:4-7). Then he promised, after 70 years, ‘I will bring my people Israel and Judah back from captivity and restore them to the land I gave to their forefathers to possess.’ (Jeremiah 30:3).

The return of the exiles under Ezra and Nehemiah, while demonstrating God’s faithfulness, never matched the glory of the Kingdom under David or Solomon (Ezra 9:8-15; Nehemiah 9:28-37). And yet, while the second Exodus may have been more subdued, Jeremiah describes it as far more significant than the first.

“So then, the days are coming,” declares the LORD, “when people will no longer say, ‘As surely as the LORD lives, who brought the Israelites up out of Egypt,’ but they will say, ‘As surely as the LORD lives, who brought the descendants of Israel up out of the land of the north and out of all the countries where he had banished them.’ Then they will live in their own land.” (Jeremiah 23:7-8)

Probably the greatest contrast between the two, however, concerns how the people living in the land were to be treated. These are the instructions God gave to the returning exiles:

You are to distribute this land among yourselves according to the tribes of Israel. You are to allot it as an inheritance for yourselves and for the aliens who have settled among you and who have children. You are to consider them as native-born Israelites; along with you they are to be allotted an inheritance among the tribes of Israel. In whatever tribe the alien settles, there you are to give him his inheritance,” declares the Sovereign LORD. (Ezekiel 47:21-23)

So in the second Exodus the Israelites are commanded to share the land with the ‘aliens’ and treat them as equals – as ‘native-born Israelites. This return was to be peaceful and conciliatory. Although radical, this was entirely consistent with the instructions given in the Law (Leviticus 19:33-34. See also Isaiah 56:3-8). The ‘Promised Land’ under the Old Covenant was to be shared and inclusive. This is the biblical model many Palestinians who favour the One State solution, long to see applied by the modern State of Israel.

The Promised Land in the New Covenant

Under Persian, then Greek and then finally Roman occupation, the Jewish people longed for a Messiah to liberate them from the humiliation of foreign domination (Luke 1:68-79; John 6:14-15). This is probably why, after the resurrection of Jesus, but before they came to recognise him, the disciples lamented his failure to restore political sovereignty to the Jews. This is reflected in their conversation on the road to Emmaus, ‘we had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel’ (Luke 24:21).

Is Jesus going to restore the Kingdom to Israel?

After recognising him as Lord and King, they then ask, ‘Lord, are you at this time going to restore the kingdom to Israel?’ (Acts 1:6) It is interesting that in this question, the Apostles at least, see ‘Israel’ as having a separate existence as a people without sovereignty in the land. In his commentary, John Calvin writes, ‘There are as many mistakes in this question as there are words.’[14] John Stott, in his commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, succinctly appraises errors made:

The mistake they made was to misunderstand both the nature of the kingdom and the relation between the kingdom and the Spirit. Their question must have filled Jesus with dismay. Were they still so lacking in perception?… The verb, the noun and the adverb of their sentence all betray doctrinal confusion about the kingdom. For the verb restore shows they were expecting a political and territorial kingdom; the noun Israel that they were expecting a national kingdom; and the adverbial clause at this time that they were expecting its immediate establishment. In his reply (7-8) Jesus corrected their mistaken notions of the kingdom’s nature, extent and arrival.[15]

Since the Holy Spirit had not been given, the disciples may be forgiven for still holding to an Old Covenant understanding of the Kingdom with the reestablishment of the monarchy and liberation from the brutal colonialism of Rome. Had they been present at Jesus’ trial they might have understood things differently. Jesus explained, ‘My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jews. But now my kingdom is from another place’ (John 18:36).

Jesus repudiated the notion of an earthly and nationalistic kingdom on more than one occasion (see John 6:15). This is why, in reply to the disciples, Jesus says that he has another agenda for the Apostles:

It is not for you to know the times or dates the Father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth. (Acts 1:8)

The kingdom which Jesus inaugurated would, in contrast to their narrow expectations, be spiritual in character, international in membership and gradual in expansion. And the expansion of this kingdom throughout the world would specifically require their exile from the land. They must turn their backs on Jerusalem and their hopes of ruling there with Jesus in order to fulfil their new role as ambassadors of his kingdom (Matthew 20:20-28; 2 Corinthians 5:20-21). The Acts of the Apostles suggests that they needed something of a kick-start to get going. It is only when the Christians in Jerusalem experience persecution following the death of Stephen and are scattered that they begin to proclaim the gospel to others (see Acts 8:1-4). The Church was sent out into the world to make disciples of all nations but never told to return. Instead Jesus promises to be with them where ever they are in the world (Matthew 28:18-20).

The Fig Tree and David’s Fallen Tent

Those who believe the New Testament speaks of a third Jewish return to the Land quote the illustration of the fig tree in Matthew 24 and ‘David’s Fallen Tent’ in Acts 15:13-17. Let’s look at each briefly.

Now learn this lesson from the fig tree: As soon as its twigs get tender and its leaves come out, you know that summer is near. Even so, when you see all these things, you know that it is near, right at the door. I tell you the truth, this generation will certainly not pass away until all these things have happened. (Matthew 24:32-34)

The followers of Jesus understood him to be warning them to heed the signs and flee Jerusalem when the city came under Roman siege. Hal Lindsey, however, reverses its meaning. He claims Jesus was predicting the restoration of the Jews to Palestine in the 20th Century rather than their departure in the 1st Century. How does he justify that?

But the most important sign in Matthew has to be the restoration of the Jews to the land in the rebirth of Israel. Even the figure of speech “fig tree” has been a historic symbol of national Israel. When the Jewish people, after nearly 2,000 years of exile, under relentless persecution, became a nation again on 14 May 1948 the “fig tree” put forth its first leaves.[16]

You may need to read that again slowly. Do you see it? I don’t either. Its called ‘clutching at straws’ or maybe in this case, ‘figs’, reading back into a passage a subjective interpretation based on hindsight rather than foresight. Nothing in Matthew 24 leads us to believe Jesus wanted his hearers to understand that he was promising Israel would become a nation state once again. As we have already seen, Jesus has used the analogy of the fruit tree before ‘Therefore I tell you that the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people who will produce its fruit.’ (Matthew 21:43). Indeed, Jesus says that the subjects of the kingdom, that is, unbelieving Jews, will be ‘thrown outside’ (Matthew 8:10-12); none of those who were originally invited ‘will get a taste of my banquet’ (Luke 14:15-24). Nevertheless, Lindsey has popularised the notion that the return of Jewish people to Palestine since 1948 is somehow the fulfilment of biblical prophecy. Where did he get the idea from? Probably Cyrus Scofield.

Referring to Acts 15, Scofield asserts, ‘dispensationally, this is the most important passage in the NT’, since he claims, ‘It gives the divine purpose for this age, and for the beginning of the next.’[17] Here is the passage in question:

After this I will return and rebuild David’s fallen tent. Its ruins I will rebuild, and I will restore it, that the remnant of men may seek the Lord, and all the Gentiles who bear my name, says the Lord, who does these things that have been known for ages (Acts 15:16-18).

James is simply quoting from Amos to show that Pentecost was not an accident but had been predicted long ago. Amos foresaw how David’s royal dynasty would be restored after the exile through one of his descendents – Jesus – and that through his victory on the cross and his reign over the nations, the Gentiles would also seek to enter his kingdom along with a Jewish remnant. Scofield, however, reads into this passage what is not there, while at the same time he obscures what is there. It all has to do with that little phrase ‘after this’. The natural meaning is clear. James has in mind ‘after the cross’ or ‘after the ascension’ or even ‘after Pentecost’. Scofield, however, claims once again, ‘after this’ means after another 2000 years! He argues that God will one day soon ‘re-establish the Davidic rule over Israel’[18] and bring the Jewish people back to the Land so that Jesus can rule as their king in Jerusalem.

The fact is nowhere is a third re-gathering to the land explicitly mentioned in the Bible. The passages quoted by Scofield or Lindsey refer either to the first or second re-gathering to the land, or as in Amos 9, to Pentecost. It is significant that, following the rebuilding of the Temple in 516 BC, there are no further biblical references to yet another return to the Land but plenty about exile from it.

Redefining the Kingdom: An inclusive inheritance in the world

The New Testament knows nothing of this preoccupation with an earthly kingdom. As John Stott says, ‘Christ’s kingdom, while not incompatible with patriotism, tolerates no narrow nationalisms.’[19] Instead, Jesus redefines the boundaries of the kingdom of God to embrace the whole world. For example, in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus takes a promise made to the Jewish people concerning the Land from Psalm 37, and applies it to his own followers any where in the world.

|

Psalm 37:11 |

Matthew 5:5 |

| But the meek will inherit the land and enjoy great peace. | Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. |

Subsequent to Pentecost, under the illumination of the Holy Spirit, the Apostles begin to use Old Covenant language concerning the Land in new ways. Shortly after the Day of Pentecost, Peter explains how the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus had been predicted inaugurating an expanded kingdom embracing all who would trust in Jesus.

Indeed, all the prophets from Samuel on, as many as have spoken, have foretold these days. And you are heirs of the prophets and of the covenant God made with your fathers. He said to Abraham, ‘Through your offspring all peoples on earth will be blessed. (Acts 3:24-25)

Here Peter claims that the promise made to Abraham (Genesis 12:3; 22:18) and repeated to Isaac (Genesis 26:4) and to Jacob (Genesis 28:14) was being fulfilled in the birth of the international community of Christ followers.

In his letter to Christians dispersed through the Roman Empire, Peter writes in terms evoking memories of Abraham’s journeying (Genesis 23:4); David’s prayer (1 Chronicles 29:15) and the Jewish exiles in Babylon (Psalm 137:4). They are, he says, ‘God’s elect, strangers in the world, scattered…’ (1 Peter 1:1). He assures them, nevertheless, that their inheritance, unlike the Land, ‘…can never perish, spoil or fade.’ (1 Peter 1:4).

Paul similarly asserts to the Christians in Galatia, ‘If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.’ (Galatians 3:29). In his letter to the Church in Ephesus, he specifically applies the fifth commandment as promising of an inheritance to Christian children.

|

Deuteronomy 5:16 |

Ephesians 6:1-3 |

| Honour your father and your mother, as the LORD your God has commanded you, so that you may live long and that it may go well with you in the land the LORD your God is giving you. | Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. “Honour your father and mother”–which is the first commandment with a promise “that it may go well with you and that you may enjoy long life on the earth.” |

Children who willingly submit to the authority of their parents will, Paul promises, enjoy long life where ever they live on the earth.

When Paul meets the elders of the church in Ephesus on the beach at Miletus, he assures them a share in the same inheritance. ‘Now I commit you to God and to the word of his grace, which can build you up and give you an inheritance among all those who are sanctified’ (Acts 20:32).

The Kingdom Revealed in the Mystery of Christ

But what of the hopes of the Jewish people in the New Covenant? Paul visualised a more glorious future for the Jewish people – but not back in their land, rather in a covenant relationship with their Messiah, the Lord Jesus Christ (Romans 9-11).

In Romans 9 where Paul emphasises how the Lord has not forgotten the Jewish people and that their hardening toward the Gospel is only temporary, he lists the blessings they have received.

I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were cursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my brothers, those of my own race, the people of Israel. Theirs is the adoption as sons; theirs the divine glory, the covenants, the receiving of the law, the temple worship and the promises. Theirs are the patriarchs, and from them is traced the human ancestry of Christ, who is God over all, forever praised! Amen.(Romans 9:2-5)

Significantly, Paul omits only one blessing, the Land. There is no suggestion in Romans that the future salvation of the Jews is related in any way to the Land. Instead Paul has already said, ‘It was not through law that Abraham and his offspring received the promise that he would be heir of the world, but through the righteousness that comes by faith.’ (Romans 4:13) The children of Abraham are those Jews and Gentiles who through faith in Christ have been made righteous. Together they have been made ‘heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ.’ (Romans 8:17).

In his letter to the Ephesians, Paul explains that this progressive revelation of the will of God had been a mystery hidden until Jesus appeared.

In reading this, then, you will be able to understand my insight into the mystery of Christ, which was not made known to men in other generations as it has now been revealed by the Spirit to God’s holy apostles and prophets. This mystery is that through the gospel the Gentiles are heirs together with Israel, members together of one body, and sharers together in the promise in Christ Jesus. (Ephesians. 3:4-6)

The Kingdom which Jesus heralded is therefore now internal not territorial. It is universal not tribal. When the Pharisees asked Jesus when the Kingdom of God would appear, he replied, “The kingdom of God does not come with your careful observation, nor will people say, ‘Here it is,’ or ‘There it is,’ because the kingdom of God is within you.” (Luke 17:20-21). Jesus shatters the exclusive geographic straight jacket of the Pharisees and liberates the meaning of the covenant made with Abraham.

The inheritance of the saints was ultimately never an ‘everlasting’ share of the territory in Palestine but an eternal place in heaven. Indeed, the Book of Hebrews shows that even Abraham, the Patriarchs and later Hebrew saints looked beyond Canaan to ‘another’ country in which the covenant promises of God would be fulfilled

“For he was looking forward to the city with foundations, whose architect and builder is God. And by faith even Sarah, who was past childbearing age, was enabled to bear children because she considered him faithful who had made the promise. And so from this one man, and he as good as dead, came descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as countless as the sand on the seashore. All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them… These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect.” (Hebrews 11:10-16, 39-40).

There is therefore no evidence that the Apostles believed that their inheritance was in Palestine, still less that the Jewish people had a divine right to the Land in perpetuity, or that Jewish possession of the Land would be an important, let alone central, aspect of God’s purposes for the world.

The land had served its purpose – to provide a temporary residence for the ancestors of the Messiah, David’s greater Son, to host the incarnation, a home for the Lord Jesus Christ, and so be made for ever holy through the shedding of his innocent blood upon it. The Land provided a base, a strategic launch pad for God’s rescue mission, from which the apostles would take the good news of Jesus Christ to the world. In the New Testament, the Land, like an old wineskin, had served its purpose. It was and remains irrelevant to God’s ongoing redemptive purposes for the world.

Chapter Summary Points

- The covenant promises made to the Patriarchs concerning the Land were understood as having been fulfilled in the Old Testament.

- The Land, like the earth itself, belongs to God and his people were at best aliens and tenants with temporary residence.

- Residence in the Land was always conditional and inclusive.

- Jesus repudiated a narrow nationalistic kingdom.

- His kingdom is spiritual, heavenly and eternal.

- This is the inheritance of all who trust in Jesus Christ.

Passages to Review

Genesis17:1-8; Deuteronomy 2: 1-9; Deuteronomy 28:1-10, 15-16, 63-64; Psalm 105:6-11, 37-45; Ephesians 3:4-6; Romans 9; Hebrews 11:10-16.

Questions for Further Study

- Who was the Holy Land promised to and why?

- What requirements were given for residency?

- What significance does the Holy Land have in the New Testament?

- What is the Christian’s inheritance?

[1] David Brickner, “What do we think about modern Israel?” Jews for Jesus Prayer Letter, April 1998, http://www.new-life.net/israel.htm [Accessed August 2006]

[2] International Christian Zionist Congress Proclamation, The International Christian Embassy, Jerusalem, 25-29 February, 1996. http://christianactionforisrael.org/congress.html [Accessed August 2006]

[3] Scofield, Scofield Reference Bible, p. 250.

[4] Arnold Fruchtenbaum, ‘The Land is Mine’, Issues, 2.4, July 1982, http://www.jewsforjesus.org/publications/issues/2_4/land [Accessed August 2006]

[5] Patrick Goodenough, Letter from the International Christian Embassy to Christian Peacemaker Teams, 31 October 1997, ‘Blessing Israel? Christian Embassy Responds, Kern Replies http://www.cpt.org/archives/1997/nov97/0000.html [Accessed August 2006]

[6] Exobus http://www.exobus.org [Accessed August 2006]

[7] Christian Friends of Israeli Communities http://www.cfoic.com [Accessed August 2006]

[8] Scofield, Scofield Reference Bible, p. 25, Note.

[9] Schuyler English, The Scofield Study Bible, Rev. (New York, Oxford University Press, 1967), p. 293.

[10] Schuyler English, The New Scofield Study Bible (New York, Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 217.

[11] Hal Lindsey, The Road to Holocaust (New York, Bantam, 1989), p. 180.

[12] Charles H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students (London, Passmore & Alabaster, 1893), p. 100.

[13] Charles H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students, First Series (London, Passmore & Alabaster, 1877), p. 83.

[14] John Calvin, The Acts of the Apostles 1-13 (Edinburgh, St Andrew’s Press, 1965), p. 29.

[15] John R. W. Stott, The Message of Acts (Leicester, Inter-Varsity Press, 1990), pp. 40-41.

[16] Hal Lindsey, Late Great Planet Earth, p. 53.

[17] Cyrus Scofield, Scofield Reference Bible, fn. 1, pp. 1169-1170.

[18] Cyrus Scofield, Scofield Reference Bible, fn. 1, p. 1170.

[19] John Stott, The Message of Acts, p. 43.