:

By Sahar Huneidi

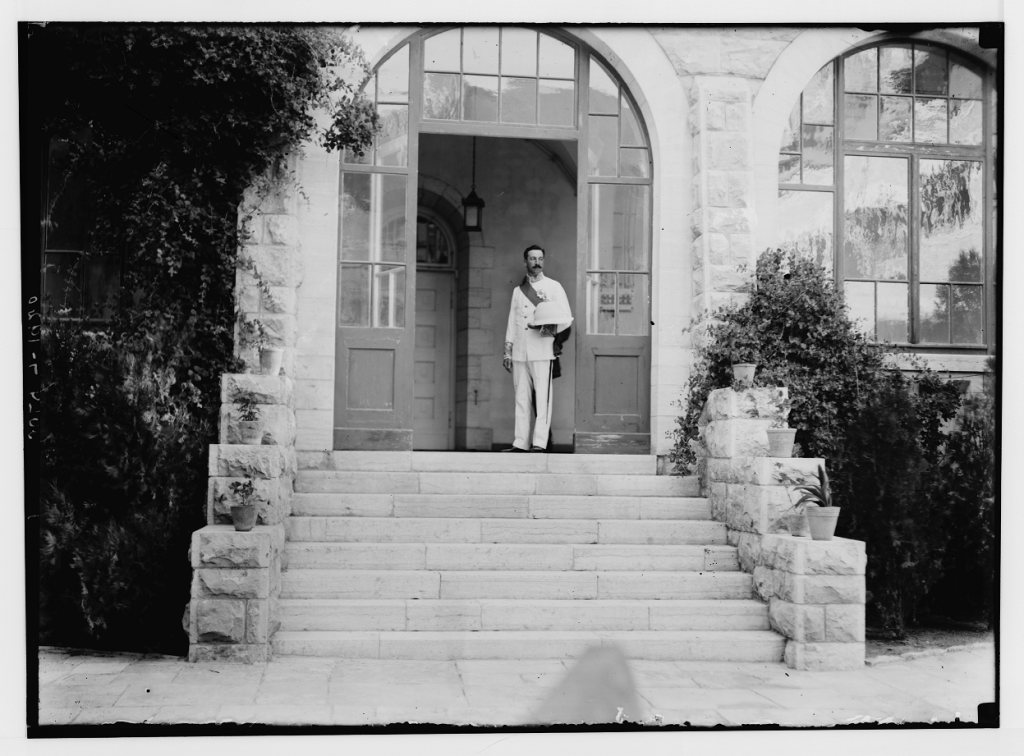

The twin issues of land and immigration are today, as they were in the early 1920s, the crux of the problem between Israel and the Palestinians. Herbert Samuel, first British High Commissioner in Palestine (1920-25), set the precedent of the policy of ‘facts on the ground’ by reshaping land ownership through a complex set of land laws, while Palestine was legally a British occupied territory bound by the Hague convention. These laws were passed to the Israeli state by which it later claimed public ownership of Palestine.

Herbert Samuel, first British High Commissioner in Palestine (1920-25), set the precedent of the policy of ‘facts on the ground’ by reshaping land ownership through a complex set of land laws

I will be looking into the events leading up to the Balfour Declaration, as well as the strategies and tactics pursued by Samuel in three distinct phases, each with its different objectives and challenges:

1914-1917: Preparing the ground for the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a deliberately vague document. It contained two pledges that were later judged by the 1937 Peel Commission as incompatible. The first pledge, that the British government ‘view[ed] with favour’ the establishment of ‘a Jewish national home in Palestine’, was, according to the Peel report, ambiguous as to the character of that ‘national home’. The national home, however, was to be established on condition that the civil and religious rights of ‘existing non-Jewish communities’ would be safeguarded. Moreover, this ‘dual obligation’ did not clarify how far the existing population could have a say in extent or character of the Jewish national home.

This inherent ambiguity allowed British officials to interpret the commitments given in the Balfour Declaration in different ways: Is it a state? Is it an exclusive state? Is it a cultural centre? A safe haven? It was ambiguous and it was meant to be ambiguous. It was precisely this ambiguity that gave enough room for a committed Zionist like Samuel to interpret the Balfour declaration in the most extreme Zionist sense, while a much more reserved interpretation was also possible. Colonial Office (CO) officials dealing with Palestine each had his own understanding of the term. Indeed, the Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Devonshire, wrote in a secret memorandum on 17 February 1923: ‘Prior to 1921, no authoritative explanation was ever given of what precisely was meant by a ‘National Home’ for the Jews.’

When a new conservative government less sympathetic to Zionism came to power in 1922, it was decided to look into the origins of the Balfour Declaration. Curiously, colonial office officials discovered that the CO held no such records, and when Foreign Office files were searched, nothing was found in them either. The CO admitted that the relevant papers had been “unfortunately dispersed”, and that “little referring to the Balfour Declaration has been found among such papers as have been preserved”.

Although the Colonial Office in the end submitted a memorandum on the “History of the Negotiations leading up to the Balfour Declaration”, it conceded that the memorandum was “very inadequate’, and that the material available could not provide a ‘complete and connected narrative”. It was nevertheless submitted, to quote the head of the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office, Sir John Evelyn Shukburgh “ as a humble experiment in the art of making bricks without straw”. It is peculiar that merely five years after the Balfour Declaration was issued, there was no record of its history in British archives. Were these documents deliberately concealed? Were they destroyed? It is difficult to answer, but tempting to speculate.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in November 1914, when Britain reversed its traditional eastern policy of maintaining the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, Samuel realised the opportunities that this new policy had opened for the Zionist movement. Although up to this point he had had no previous interest in Zionism, he submitted between January and March 1915, two memoranda: the first to PM Asquith and a second and revised one to the Cabinet. In these memos, Samuel advocated the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine under British protection, claiming that this was fully recognised by the Zionist movement. He wrote in his memoirs: ‘The break-up of the Turkish Empire, long overdue, was now almost inevitable. The future of Palestine would raise a question of the greatest interest. It became plain at once that Zionism had acquired a new actuality – vivid, urgent… Events that were unexpected gave me a share in the writing of this chapter.’ Although this effort produced no tangible results, it placed the Zionist agenda on the highest level for serious political discussion. Samuel saw himself as only the second Jew after Disraeli to have reached such a high political level and seized the opportunity of making himself useful to the Jewish cause. In 1915 Mark Sykes appeared on the political stage, and despite his little knowledge he came to be regarded as ‘expert’ on the Middle East ( a term he coined) just because he had travelled in the area and had some first hand knowledge of it. Sometime after his secret agreement with the French in 1916 (Sykes-Picot Agreement), he initiated negotiations with leading Zionists, and got in touch with Herbert Samuel hoping to learn more about Zionism. This in spite of the conclusion of the de Bunsen Committee (30 June 1915) that Palestine and Zionism were of little concern to the imperial needs of Britain. Sykes was convinced of the power of world Jewry to sabotage the Allied cause and that they had to be pacified. However, it is important to mention that Sykes’ vision of what Zionism implied seems to have been at variance with the more extreme Zionist interpretations. For instance, in February 1916 he wrote to Samuel saying: ‘I imagine that the principal object of Zionism is the realization of the ideal of an existing centre of nationality rather than boundaries or extent of territory’. It was thus during 1916 that we get closer to the forces that drove the British government towards a more or less well defined pro-Zionist policy. The year 1916 was a near catastrophe for the Allies, and Lloyd George who came to power in December of that year was a pro-Zionist sympathiser.

1917- 1920: Relentless Zionism

In January 1917, Weizmann, took the initiative, and mainly with the help of Norman Bentwich, (later to become Legal Advisor under Samuel in Palestine) submitted a memo to Mark Sykes entitled ‘ Outline of a programme for the Jewish Resettlement of Palestine in Accordance with the Aspirations of the Zionist Movement’. According to Weizmann, this attempt was the ‘first approach to the integration of Zionism with the complex of realities’. The memorandum emphasised two points: first, it asked for the recognition of the Jewish nation, and second, for the right of this nation to settle in Palestine with full civic, national and political rights. These objectives were similar to those advocated by Samuel in 1915. As Sykes himself was getting more committed to the Zionist cause, it became clear to him that the Sykes–Picot agreement was an obstacle to Zionist aspirations. During the course of 1917 the military situation of the Allies continued to deteriorate on all fronts. Britain was faced with a near starvation situation, and a War.

Cabinet memo stated in February 1917 that the present stock of wheat in the UK was enough for only 12 weeks consumption. In March Russia ceased to be an effective ally when the Bolshevik revolution broke out, and the British offensive in Palestine and Mesopotamia had failed during the same month. To add to all this, German submarine warfare was inflicting heavier losses with each month. Disasters on the Western Front made the Eastern Front especially crucial. A War Cabinet memorandum argued in April 1917 that Palestine and Mesopotamia under hostile control would pose a threat to Britain’s lifeline eastward. Lloyd George took immediate steps and launched the great offensive in the East. He sought to secure Britain’s aims in Palestine through every means available: military, diplomatic and political. From then on, developments towards the issuance of the Balfour Declaration took a life of their own. It was believed that the Balfour Declaration would mobilise world Jewry east and west in favour of the Allied cause. The months from April to November 1917 witnessed frantic efforts both in Britain and across the ocean with leading American Zionists towards securing a pro-Zionist declaration. However, it was later admitted by British officials that no such benefit had ever been accrued from such effort.

All through this critical period in the few months preceding the Balfour Declaration , Samuel was busy giving Weizmann all the help he needed to further the Zionist cause. Thus, on 25 April 1917, Weizmann met Herbert Samuel who apparently leaked to him the information that the Sykes-Picot agreement was now unacceptable from the British point of view. Samuel moreover advised Weizmann to see the Foreign Office and paved the way for him to see Lloyd George. In October 1917, the British War Cabinet acted on the evidence that the Germans were about to make their own pro-Zionist declaration and decided to hear the views of 10 representative Zionist and non-Zionist Jews. In the meantime, the draft declaration under consideration was to be referred confidentially to President Wilson. On 31 October, the question came once more before the War Cabinet, and a number of additional papers were presented at this meeting. Samuel wrote that if the Turks were left in control of Palestine, the country was likely to fall under German influence. He argued that Egypt would be exposed if Germany was left dominant there, and that the best safeguard would be the establishment of a large Jewish population under British protection, adding that this would be “calculated to win for the British Empire the gratitude of Jews throughout the world”.

In the same meeting of 31 October 1917, seven variants of the proposed draft Balfour Declaration were presented. One of these drafts had previously been submitted by Lord Milner to the war cabinet (on 4 October 1917). It was this draft, and the Zionist leaders’ minor alterations to it that was finally approved by the War Cabinet which we all know as the Balfour Declaration of November 2nd. In the final analysis, it was these short term political considerations, coupled with British imperial interests and the concept of the restoration of Jews to their promised land which combined to produce the Balfour Declaration.

************

Following the defeat of the Turks and Allenby’s victorious entry into Jerusalem in December 1917, a military administration under the name Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (OETA) was set up, and a Zionist Commission, headed by Chaim Weizmann, arrived in Palestine early in 1918. Its mission was to give effect to the Balfour Declaration and to form a link between the British authorities and the Jewish community. The arrival of Weizmann in Palestine as the head of the Zionist Commission cemented his role as the undisputed leader of the Zionist Organisation. In 1919 the American King-Crane Commission of Inquiry determined that Zionism was the root of Arab hostility to the British administration, and strongly recommended to the League of Nations that the unity of Syria and Palestine should be maintained under one single mandate. The King-Crane commission also proposed serious modifications to the Zionist programme, and strongly recommended a constitutional monarchy with King Faisal – symbol of the emerging Arab nationalism- as its head. Samuel, however, saw the danger of such a move to Zionist aspirations. He immediately telegraphed to Curzon that recognising Faisal as king of Syria and Palestine ‘…would tend to take life out of Zionist movement’. This had far reaching consequences to the future of the Middle East. In spite of the findings and recommendations of the King-Crane commission, and as many scholars have noted, perhaps because of them, the findings of the King-Crane commission were kept from public knowledge for many years. From January-March 1920 Samuel was sent on an official visit to Palestine to assess the administrative and financial situation in Palestine. Contrary to the facts that the military administration knew only too well, Samuel reported that there was no genuine Arab hostility to Zionism. He added that Palestine, under populated and underdeveloped, could support millions of Jewish immigrants. At the same time as he was misleading the British government, he warned Weizmann that the Zionist Commission had the effect of an ‘alien body in living flesh’ and that he did not expect to convert Arabs.

1920-25: Facts on the ground and the politics of Chose Jugee

Samuel provided Zionists with the momentum with which they could make ultimate statehood possible, and gave the Balfour Declaration a concrete base on which legislation in the political, economic and demographic spheres were translated into realities and facts on the ground. Such measures were sometimes adopted without the knowledge or even approval of the government in London. One example is a puzzling 1920 postage stamp issue that not many know about. The new stamp that Samuel had just issued soon after he took office, as expected, bore the name of Palestine in the three official languages: Arabic, English and Hebrew. But Samuel managed to sneak the letters ‘Aliph and Yod’ to signify the words ‘Eretz Yisrael’ next to the Hebrew letters only. Obviously, Samuel had no right to do this, and as expected, Foreign Office officials questioned his action, but the issue was quickly forgotten as responsibility for Palestine was passing from Foreign Office to Colonial Office control, so the subject was closed . It was noted that this was the first official use of the title ‘Eretz Yisrael’ as applied to Palestine. Israel was thus first born on a postage stamp! When it came to the arming of Jewish colonies, Samuel took no less deviant measures and went ahead with arming the colonies without the explicit approval of the government. Such measures, at many times expressly unacceptable to the government in London, paved the way for the Haganah, the nucleus of the Israeli armed forces. When the controversial Jewish Community Ordinance was being drafted, he was no less adamant in furthering Zionist policies and in acting independently from the instructions of the colonial office. The Jewish Community Ordinance of 1925 gave the Jewish community autonomous political powers including the right to levy taxes, in effect, it was the Israeli Knesset in waiting. As Samuel was implementing those measures, it is important to remember that the new civil administration remained a de facto administration, since the mandate only came into force as late as September 1923. Nevertheless, the status quo of the country, still technically bound by wartime restrictions, was being inequitably prejudiced in favour of a small Jewish minority. Samuel passed laws in his first two years, not to mention the first two months, that would change the status quo of the country to the detriment of the Arabs. As he created those facts, Samuel was fully aware that he was treading on precarious grounds. He kept pressing the Colonial Office for what he called a ‘regularization’ of the situation in Palestine, and repeatedly wrote that ‘the circumstances of the country have called for considerable measures of legislation that go far beyond the powers of an ordinary military occupant’. On the other hand, Samuel was well aware that legislation was needed in the political, economic and administrative spheres to turn the majority into a minority and vice versa. To achieve his goal, he appointed the staunch Zionist Norman Bentwich as Attorney General. It was Bentwich who kept the Zionist Organisation fully informed of new ordinances while being drafted. This greatly assisted Zionists on the vital issues of land legislation and purchase. Between 1920-25, no less than ten Ordinances on land related issues were passed. The first Land Transfer Ordinance was issued in September 1920, and was the first step that ultimately allowed Zionists to gain control over large tracts of state land. Under these land laws, for the first time the notion of land use became distinct from land ownership. These land laws would also later result in the creation of a dispossessed class of Palestinian tenant farmers who had clear legal rights under Ottoman law, but became liable to eviction by court orders under Samuel’s land policy. His other most immediate priority was legislation in the field of immigration. Between 1919-1923 the size of Jewish settlers doubled and the number of colonies increased to about 100. These new immigrants were soon given the opportunity to participate in local elections by granting them provisional Palestinian citizenship, followed by full citizenship only after 2 years. The demographic balance in Palestine was being seriously altered. Among the other measures in favour of the Jewish community was the setting up of the Department of Commerce and Industry, and the establishment of banks to grant long term loans to Jewish agriculturists and urban businessmen. Also, a large programme of public works, -including road construction- was immediately begun. It was often pointed out by the Palestinian leadership that this road building scheme was mainly meant to connect Jewish settlements and was a major source of Jewish employment and not to the benefit of the country as whole. And to help Jewish building activities, Samuel reduced customs duty on building material from 11% to 3%. Thus, between 1920-23, Samuel engaged in a development oriented policy of large public investment and infrastructure projects vital as a source of employment to Jewish immigrants. He went even further than this by laying the foundations of future vital projects such as Haifa harbour when he discussed it at length in his 1925 report under the heading ‘Future Work’. ! On the political level, Samuel made the phrase ‘self-governing institutions’ in the mandate apply only to Jews, and prevented Palestinians from exercising their authority in the political and economic fields. When he fully recognised the Jewish National Assembly as the official elected representative of the Jewish community, he denied the same to the Arabs. He thus prepared the Jews for political and economic ascendancy and gave them wide powers calculated to block the road to Palestinian self-determination.

What was Samuel’s understanding of the Balfour Declaration?

Under pressure, Samuel made the first public attempt to interpret the Balfour Declaration in a speech on 3 June 1921, following the eruption of violence, in Jaffa, in May of that year. He claimed that there was ‘an unhappy misunderstanding’ about the declaration. ‘It did not mean’, he stated, that the country would be taken away from its Arab owners and given to Jews. It was also Samuel who drafted the first official and written interpretation of the Balfour Declaration in the 1922 White Paper. This remained the central document guiding British policy in Palestine until 1929 . The White Paper asserted that Jews were in Palestine ‘as of right and not on sufferance’, and added that the British government ‘did not contemplate the subordination or disappearance of the Arab population, language or culture’. This confirmed the ambiguity of the Balfour Declaration, since it did not resolve the question as to how the Jews could be in Palestine by right, without infringing on the rights of the local inhabitants. Throughout his five years in Palestine, Samuel never ceased to insist on the phrase that the Balfour Declaration was a chose jugee, a closed issue – he coined that phrase – and irreversible. By insisting that the Balfour Declaration was irreversible, he was hoping to make it so, while in fact this could not be further from the truth.

As already mentioned, it was during 1922-23, that doubts in British government circles that the Balfour declaration was a political mistake were expressed loudly. The possibility of reversing the whole Zionist policy was very real, following a House of Lords motion rejecting the mandate on grounds of inherent injustice to the Palestinians. But Samuel again came to the rescue: he tipped the scale in favour of Zionists when he appeared before the Cabinet sub-committee in June 1923, -which met to review British policy in Palestine and was chaired by Lord Curzon – by insisting that the Zionist policy was not susceptible to change. He prevented Palestinian representatives from appearing before the committee and was the only one invited. Consequently, the subject was closed and no further revision of Zionist policy took place after 1923.

Conclusion

Within a decade, after Samuel first envisioned a Jewish state in Palestine in his 1915 Cabinet memorandum, the project was well under way by 1925. He was heartily congratulated by the Zionist Organisation on the successful completion in 1925 of the first stage of the Jewish national home. Since 1925, and up to the present day, further injustices were inflicted on the Palestinians as a result of the Balfour Declaration. Though it is important to revisit the root origins of the problem now, it is more important to right the wrongs.

This paper was first given at the Scottish Friends of Palestine conference Palestine and the Legacy of Balfour, Haddington in 2005. Dr Huneidi also spoke at a Balfour Project conference in 2013. Dr. Huneidi is a historian and political scientist concentrating on political history in Palestine. She is a director of the London-based East & West Publishing, an independent publisher concentrating mainly on history and art history. Her books include A Broken Trust: Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians.